Adam Shead is not your typical bandleader. As the driving force behind Chicago's experimental ensemble microplastique, Shead brings a unique perspective to his role as composer and percussionist, drawing on a background that includes hardcore punk, free jazz, and contemporary classical music.

In this unguarded conversation, Shead provides insight into his artistic process, the formation of microplastique, and the group's debut album blare blow bloom!. He discusses the influence of artists like Roscoe Mitchell and Marilyn Crispell on his work and how his time with the no-wave band Cellular Chaos has shaped his approach to music-making.

Shead's thoughts on topics like class dynamics in the improvised music world and egalitarian approaches to music-making offer a less-heard take on the current state of experimental music. His commitment to creating "a space for introspective presence" through his art underscores the depth of thought behind microplastique's seemingly whimsical approach.

I feel fortunate to have experienced this sensitive discussion with an artist unafraid to challenge conventions and push the boundaries of what's possible using a collection of tiny instruments and a lot of imagination.

The Mind of an Artist

Lawrence Peryer: How do the different art forms you work in influence your creative process?

Adam Shead: They influence me the most in terms of process and theory. I enjoy reading about painters' and photographers' ways of working. I'm reading a book on color theory by Josef Albers right now. I'm sure that will bear great musical fruit. Ultimately, painting, photography, and poetry are part of my practice, but they hold less weight than music. I find them wonderful reprieves during moments of musical burnout. I'm not trained in them, so this lack of training allows me to think artistically without so much baggage. I can then pretty easily transfer these non-musical discoveries into something sound-based.

Lawrence: You've spoken elsewhere about creating "a space for introspective presence." Can you elaborate on this?

Adam: I got into Schenkerian musical analysis during my undergraduate studies, which is about stripping away ornamentation to understand a piece's foundational or structural elements. It's like looking at a skyscraper and taking everything away until only the steel beam skeleton stands before you. Then, you rebuild the skyscraper, creating this almost tiered system of value to musical elements. You can ask, "What is of the utmost importance to accomplish the message, intent, or whatever the composer wants, and what is frivolous ornamentation that doesn't add to the work outside of a glossy finish?" In other words, "What is utilitarian and functional, and what is just kind of there that does not hold much depth?" I have found it helpful in identifying the micro and macro of a musical piece simultaneously—understanding the kernel of the idea and the butter dressing of the popped corn. But I think maybe Schenker hated butter.

As a composer, performer, and listener, I often think through this Schenkerian lens for better or worse. This kind of thinking allows me to uniquely view the relationship between different musical elements, sounds, voices, and performers. I’ll often be listening to music and think, “Okay, so how does this low register ostinato from sound x relate to the silence between notes of performer y, and how does their relationship relate to the overall idea of the work?”. From there, I find myself extrapolating these findings and relating them to my life, whether it be what is going on in my professional, personal, or romantic life. I can generally form a relationship with the music that helps me grow or provides insight into what's happening in my head. So, in that sense, introspective presence is the space where one can be fully present to consume a piece of art and let it move you, let it allow you to think deeply about who you are, who you want to be, how you relate to the world, etc.

I’m not interested in music as entertainment; to be quite honest, it’s been a long time since I’ve been able to listen to a piece of music without wanting to find a sense of meaning for myself. It's not the “What did the artist mean, what was their intent?” kind of meaning—that’s not worthwhile to me. I’m interested in what it means to me and my intent for the piece.

I feel I'm not being very clear, so I'll give an example. I recently premiered a new piece of music called "Rondo Gwere" for a reed quartet. The piece was performed by some amazing musicians—Jon Irabagon, Jason Stein, Mai Sugimoto, and Gerrit Hatcher. The whole concept of this piece is to investigate the relationships between the many identities all individuals hold and how mental health issues like major depression and intrusive thinking can alter and affect these identities. You know, I'm a son, I'm a partner, I'm a drummer, I'm a composer, I'm a brother, I'm a laborer, I'm a friend—all that. So, I wrote the piece to function in which three performers are a unit, with one performer acting as a type of intrusive element working to dismantle the three-performer unit and sway them toward the intrusive element.

My depression often manifests in intrusive thinking that works to dismantle my sense of self. So, I wanted to write a piece that represented that, and as a listener, the process is the inverse. Finally, as a performer, you just don't want to be thinking when you're playing, at least not too much; most things should be intuitive during performance.

Lawrence: Besides these examinations, your work explores themes like class, hierarchical structure, and egalitarianism. What experiences have led you to focus on these topics?

Adam: Unlike many artists my age working in the improvised music world, I was not raised with wealth. There has never been a professional artist in my family lineage, and I wasn't plucked up by some jazz great at a pay-to-play jazz camp when I was in high school. Because of that, I've always existed on the culture's outskirts. Even in graduate school, I couldn't find a way to fit in. There were social mores that were just so foreign to me and still are to this day. These social mores and their role in improvised music are just a product of the bourgeoisie stealing a historically working-class art form and presenting it as their own—which has often been the case with left-of-center artwork throughout history.

Suppose you look at a lot of working-class community organizing principles. In that case, they are much more democratic and egalitarian than those of the financial elite that rely heavily on the figurehead übermensch leader and a trickle-down distribution of resources. I don't think improvised music is any different than any other organization of working-class individuals who have self-respect and respect for each other. It is a practice of compromise, it is a practice of support, it is a practice of care, and it is a practice of meeting people where they are. That is successful improvisation—"If you're not making it, I'm not making it."

Lawrence: You've performed with notable artists like Roscoe Mitchell and Marilyn Crispell. How have these collaborations influenced your approach to music-making?

Adam: Working with Roscoe Mitchell and Marilyn Crispell was a fantastic experience. I played a two-hour concert with Roscoe and a two-night concert run, followed by a recording session with Marilyn. The two experiences couldn't have been any different, but they were thought-provoking and life-affirming. I remember when my trio with Jason Stein and Damon Smith played with Roscoe, he kind of just rolled into the venue, he set up, and we hit it. I didn't speak to him much, other than when he told me a story about how his dad got him to quit smoking cigarettes as I was rolling a cigarette. I remember before we started playing, I said to myself, "Fuck yes, he brought the alto"; he's not playing much alto these days.

He's probably in the top five of my biggest musical influences. Because of that, making music with him was pretty easy, and I felt we had a good connection. Whatever the audience thought about the music was out of my control, but I enjoyed myself, and it seemed he did, too. We have a recording of that concert that I'd like to see out in the world someday.

Working with Marilyn was a more in-depth multi-day experience where we shared many meals, performed four sets of music, and did a recording session that resulted in our album spi-raling horn on Irritable Mystic Records. We got close over that weekend and spoke deeply about process and life. I still exchange emails with Marilyn; she's a wonderful friend to have. We rarely talked about what we would play and spent more time discussing the 'why' of playing. I enjoy those kinds of conversations. I visited her in upstate New York not too long ago for a coffee; she's a very sincere, special person. I value that relationship deeply.

I am more inspired by these musicians than in awe. I'm not sure how helpful being in awe of another artist is for someone working in the same medium; being inspired is fantastic, but being in awe puts you below them. That doesn't help in the attempt to make work that strives to be as great as the work they have created. I am in no way saying that my work is equal to the work of these two masters, but when working with them, not at least trying to approach the work as an equal feels like a disservice to them. Not trying to contribute on their level and not having the confidence that that could be possible seems self-defeating. Being in awe or creating an idol from another artist is a good way to get stuck.

Lawrence: You've also been a member of Cellular Chaos since 2022. How has the band's punk and no-wave aesthetic influenced other musical projects?

Adam: It's a return to playing I did as a teenager. The first musical tradition I seriously dealt with was hardcore punk. I played in punk bands and made loud, noisy, fast, chaotic, and political music. Bad Brains is still my favorite band. It has been a lot of fun getting back into that playing over the last few years.

On microplastique

Lawrence: Can you tell us about the formation of microplastique and this ensemble's approach to your compositions?

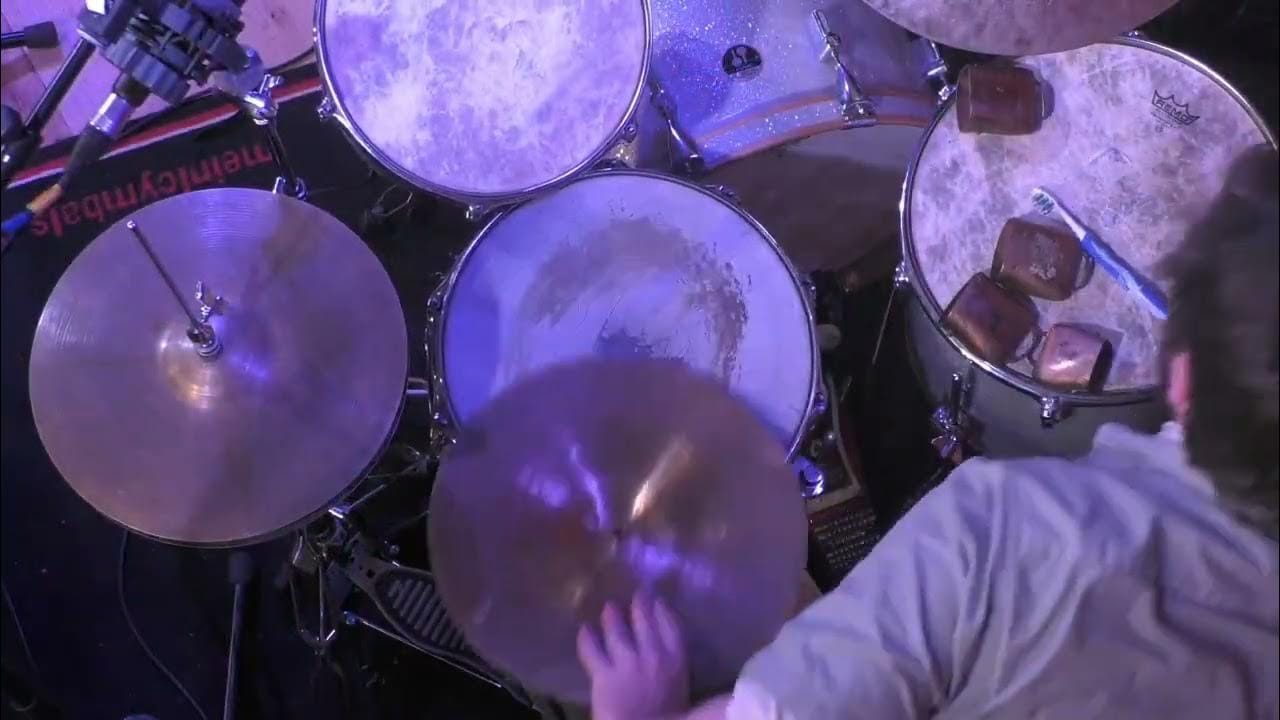

Adam: At one point in my life, I was performing a lot of contemporary classical and percussion ensemble music, a lot of stuff by Steve Reich, John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, and other tangentially associated mid-twentieth-century American composers. After some years away from that music and working primarily in a drumset-oriented free jazz context, I wanted to get back into a sound world and performance style that's percussion-forward and aleatoric while still drawing upon that free jazz tradition. I began acquiring a lot of percussion instruments that were previously only accessible in academic settings and started redefining my approach to being a percussionist. I realized that what I wanted to do with this collection of small instruments was to create an ensemble of multi-instrumentalists who can just as easily perform on percussion as they can on horns, flutes, sound effects, or whatever I throw at them. Luckily, I had already been working with Josh Harlow, Molly Jones, and Ben Zucker in various contexts over the past decade. I was confident that their sensibilities aligned with the music I was dealing with.

The ensemble's approach to the composed material has evolved dramatically over the last year, simply through repetition, familiarity with each other, and how we can stretch and alter the material. When developing fairly open, minimally composed material and allowing the musicians to perform on different instruments on a single composition from night to night, it is super important to establish a sense of what is important and what isn't. I have only given the ensemble a few key parameters to work off—melody-based theme and variation improvisation, embracing the absurd, and, most importantly, if you are doing something and it doesn't seem to make sense, don't stop! One of the other ensemble members will make sense of what is happening.

I think this idea of "don't stop!" and committing to an idea is important in keeping the momentum and forward motion of the music. While I am a big fan of a lot of music that works with stasis, silence, and stillness, I often do not have much interest in that in my music. I prefer something that takes the listener on a rollercoaster ride where they must trust the ensemble will take them somewhere interesting.

Lawrence: How do you select and incorporate these unconventional instruments into the work?

Adam: The composed material is traditional sheet music and does not dictate which instruments they should be performed on. In the band's earliest days, the default was to play the melodies on trumpet or sax with toy piano and percussion acting as the rhythm section, which still happens sometimes. As the band developed, Molly, Ben, and Josh began performing the compositions with a more whimsical approach—mutating the written material while maintaining the kernel of the idea for a given composed element.

For example, on track three of the album, a quarter note "bass line" was written for Ben to perform on the J Horn, a plastic euphonium-type instrument. Still, in this specific instance, he ended up performing that line on this squeaky toy children's trumpet thing, resulting in this absurd toy instrument feature that still retained the jaunty nature of the composition. I am not super precious about what instruments are being played as long as I can feel that the idea of the piece is represented. While each ensemble member has some main instruments they perform each night, we swap percussion instruments and sound effects to keep things interesting night after night. Since I don't assign who should play what instrument on any given piece, I am as open to discovery as the other musicians. I rarely approach the band with a piece that I feel should be played by certain instruments.

For instance, the track "walk on kedzie" was originally intended to be performed by glockenspiel, toy piano, melodica, and flute—but during rehearsals and performances, Ben continued to change which instrument he performed the piece on, creating a lot of interesting variations. Ultimately, what you hear on the record is Ben performing some great pocket trumpet lines instead of a toy piano, which adds a nice floating texture to the piece.

Another example is "bells for four"; that's a straight-up piece of minimalist composition that only happens on hand and desk bells. That piece is more interested in improvisation, providing the subtle change characteristic of minimalist composition, rather than the composer dictating such change.

So, I assign instruments sometimes, but more regularly, it is open-ended, allowing the ensemble to explore different possibilities. Generally speaking, some aesthetic parameters I've set for myself influence the compositional process most. I want the microplastique compositions to be melodic, simple, demented, and somewhat absurd. If I feel like the piece falls under those categories, it'll probably do well with microplastique.

Lawrence: How do you incorporate minimalist techniques into microplastique's otherwise eclectic sound?

Adam: The clearest example of minimalist composition comes through two pieces on the album: "walk on kedzie" and "bells for four." I mean, they are just straight-up minimalist compositions. Repetition, alteration, driving rhythm, and all are there. We are just relying on improvisation rather than composition to bring about the subtle change characteristic of minimalism. Improvising minimalism is an interesting concept; it takes a lot of patience and awareness.

Lawrence: Does the work of the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Kurt Weill influence microplastique's sound and approach?

Adam: The clearest correlation between the microplastique sound and the work of the AEC is the emphasis on small percussion and small sounds, which is more of a Roscoe Mitchell preoccupation. However, that full band did participate in that kind of work. The AEC and the work of all its members are extremely important to me as a musician and composer working in Chicago. Still, I'd say the Art Ensemble influence could be more broadly represented by the influence of the AACM on my work. I've spent as much time studying the compositions and improvisations of people like Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton, and Henry Threadgill as I have the AEC.

For example, the last track on the album, "march for MrA," is a very Threadgill meets John Tichai-inspired composition that also acts as a kind of chromatically embellished contrafact to the AEC tune "A Jackson in Your House" and is dedicated to MrA—Muhal Richard Abrams. So, while I think the AEC is a great way to give listeners a primer on what kind of sound world to expect and the influence is there, the broader influence can be more attributed to a good thirty-ish year period of the AACM. In terms of Kurt Weill, I am just a big fan of how simple but effective his melodies are; the melodic influence of Weill is probably most apparent on the fourth track, "yearning."

Lawrence: How do you balance this intense energy the group can generate with the more nuanced aspects of your compositions?

Adam: I wish we could put a score example of the compositions into this interview so everyone could see how simple the compositions are. The microplastique compositions generally utilize the first five scale degrees of a major scale with slight chromatic and rhythmic alteration, and the rest is produced through improvisation. Improvisation generally holds more weight and time than composition in a microplastique performance, so as the composer, I try to balance substance and simplicity. I'm attempting to provide enough material to provide a foundation for improvisation while limiting the complexity of the material so as not to hinder the improvisational possibilities.

There are a few good performance videos of the band on YouTube; I'd encourage readers to check them out to see how much is improvised in the band. We generally perform two sets during one concert, each with about five compositions that we weave together throughout improvisation without stopping. In contrast, you hear excerpts of these longer pieces on the album. So yeah, check out our live performance videos, and you'll see how amazing Ben, Molly, and Josh are at interpreting and expanding these very simple compositional ideas.

Check out Adam Shead at adamsheadmusic.com and follow him on Instagram and YouTube. Adam Shead can be heard performing regularly throughout the United States and Europe at venues such as Constellation, City of Asylum, Trinosophes, De Ruimte, PACA, and Zaal 100. microplastique's blare blow bloom! is out on Irritable Mystic Records.

If you enjoyed this article, then be sure to check out these:

Comments