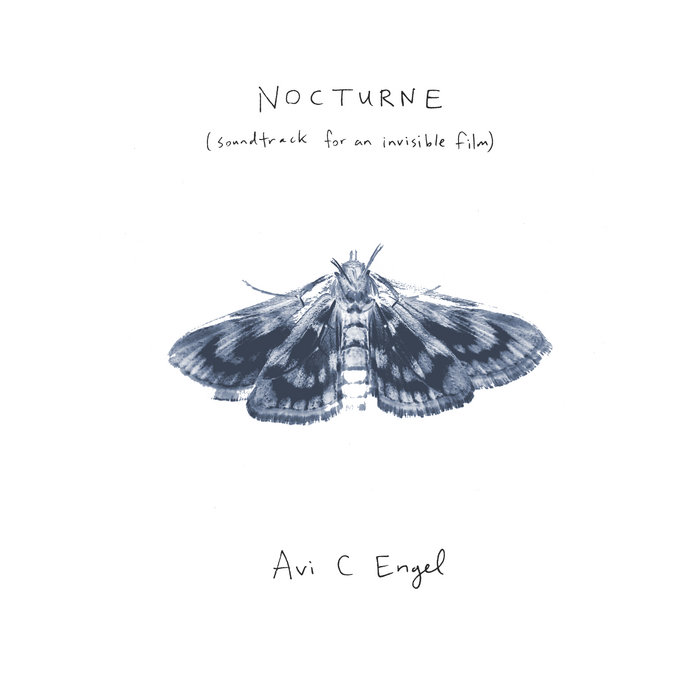

Toronto musician and visual artist Avi C. Engel has built a unique body of work over the past twenty years. Engel's music combines folk, worldbeat, ambient, and experimental elements, inhabiting the nooks and crannies between genres—hidden possibilities given new light. A self-taught multi-instrumentalist, Engel embellishes their song arrangements with improvisations played on the gudok (a traditional Slavic bowed instrument) and the talharpa (a bowed lyre from Northern Europe). The result is a symbiosis between ancient and modern forms, which is felt profoundly in Engel's new album, Nocturne (Soundtrack for an Invisible Film).

Lyrically, Engel draws upon poetic tradition as well as classic songwriting. Allusions to Blake, Roethke, Plath, and Ryszard Krynicki mingle among classic folk and blues tropes, often embellished with Engel's evocations of nature. Engel's visual art appears on the covers of thirty-six albums and EPs released over the past two decades—a prolific output growing by three or four new releases yearly. Even so, Engel continues to forge new musical paths, such as the cinematic instrumentals and haunting improvisations heard among more traditional songs on Nocturne (Soundtrack for an Invisible Film).

In an interview with The Tonearm, Engel reveals the artistic interests and creative methods involved in making Nocturne. Born "during a spell of sleeplessness and depression," the new album promises to fulfill Engel's ambition to "soothe my own mind... with the hope that it might soothe other minds as well."

Peter Thomas Webb: Your new album Nocturne is subtitled Soundtrack for an Invisible Film. How would you explain the meaning of the subtitle?

Avi C. Engel: I'm a fan of the soundtrack genre, where you often find instrumentals interspersed with songs. I've always enjoyed that kind of flow. For my songs with lyrics, I spend a lot of time developing the lyrics, so they're heavy as lyrics go. It's good to give listeners a breather and time to think about the word content as they float through an instrumental. I decided to make my own soundtracks so that people could make their films in their heads.

Peter: I notice stylistic differences in the new album, Nocturne, from some of your previous work. Along with traditional songwriting, I hear more instrumentals and soundtrack-style music. What led to this change in direction from the songs you released on the EPs Too Many Souls, Strangling Vine, and Bestiary in 2024?

Avi: A terrible allergy attack in August made it difficult for me to sing, so I just recorded instrumentals, and the album grew from there.

Peter: Can you give us a specific example of how this musical "growth" occurred?

Avi: The song "E Minor Fermented" has an interesting story. I watched a documentary about fermentation and thought I could use a similar idea in music. In the song, it's almost like I'm putting an E minor chord in a jar, and things are growing out of it. There's a guitar part at the core of it and a growing kind of delay that builds on it. A little bit of melodica also sprouts out of it. I'm the opposite of someone who's interested in arcs. I like things that seem not to go anywhere on the surface, but then there's a lot bubbling up underneath that nothingness.

Peter: Scanning your song titles, I notice many references to insects and other small organisms, especially birds. The new album, Nocturne, has titles like "Where Does the Moth Go?" and "Cocoon." What inspires this type of imagery from the worlds of nature and biology?

Avi: I feel like it's something that's grown in my music, and maybe it was always there—like a seed. In my own life, I've gotten involved in nature stewardship near where I live. I help remove invasives and plant native species, and it's probably creeping into my music—like osmosis.

Peter: You are known for playing various ancient European instruments, including the gudok and the talharpa (bowed instruments from Eastern and Northern Europe). What got you into learning to play such instruments?

Avi: I like bowed string instruments. I often worked with cellists and thought I'd like to play something in that family. Cellos are very expensive and a big life commitment, but exploring online, I found various stringed instruments I'd never heard of before. The talharpa is a weird one because there is no neck. You're just playing in the air, bending the string. It's very expressive. The gudok has a neck and is an ancient fiddle-type instrument with a deeper tone. It has a bit of a gnarly timbre, which I like.

Peter: Can you explain some recording processes you use on your albums and EPs? What techniques do you use to capture the dark and ethereal atmosphere of your recordings?

Avi: I think I've gotten freer with recording over time. It's hard for me to work in complete silence, so I've decided to embrace the space that I'm in. The performance is much more important to me than the pristine quality of the recording, and I'm less intimidated nowadays by the technical aspects. Nocturne was done with a Sennheiser mic that is normally used for drums. The recording wasn't something I had planned to make into an album; it grew into that—from an experiment with that particular microphone.

Peter: In your introduction to your 2024 EP Strangling Vine, you write that a "fallible human quality is something [you] prefer to preserve rather than conceal in [your] music." Can you elaborate on why human error and spontaneity are important to your creative process?

Avi: I think it's a fundamental preference. It's about what creeps me out when things are extremely manicured, or we try to get AI to create art. Many people like that, but it doesn't do anything for me. There's something mysterious about sounds when humans make them. There's something holistic about it, and I don't want the music to be scrubbed clean. When I listen to other people's music, I love a crack in the voice or a flub in the guitar. It makes the music feel alive and animated by a human spirit.

Peter: You often reference poetry in your work. For instance, I've noticed allusions to Blake and Roethke in your earlier work. On Nocturne, the song "Ariel" has connotations of Greek myth, Shakespeare's The Tempest, and Sylvia Plath's poetry. What inspires these parallels between your work and the world of literature?

Avi: I can't help but add to the tradition of poetry and music. If you think about how poetry was originally sung instead of spoken, my work falls into that tradition. Despite the recent instrumentals, I feel like the core of what I do is putting words to music. I don't think of myself as a singer-songwriter more as a poet who is also a musician.

Peter: In your Bandcamp introduction, you claim, "I am not writing the same song over and over so much as writing one long continuous song that will end when I die." Can you elaborate on why this musical continuum is important to your work?

Avi: I don't think I consciously took that approach; I just observed it. The seed of what I do comes from one place and expands in some direction, like a vine. I partly wrote that line out of rage when someone claimed that "all my songs sound the same." But you could say that about a lot of the people I like best, whose work I come back to. They have a strong voice, building on something, which is their life's work.

Peter: As well as a musician, you are a visual artist. Many of your works adorn the covers of your albums. Are there things in visual art different from what you evoke in your songwriting?

Avi: Good question. I feel as though it's common to work in more than one medium. For example, I'm finishing the book series Gormenghast by Mervyn Peake, in which Peake also did the illustrations. If you're the type of artist interested in making any type of alternate world, it's very satisfying to be able to express it in more than one way.

Artwork by Avi C. Engel

Peter: Where and how do your art's visual and sonic elements intersect?

Avi: I love long flowing brushstrokes and the feeling of not being entirely sure where something is going as I draw it. I trust in the line, like when improvising something musically on the gudok or talharpa. It makes me wonder if there is some cross-wiring in my brain, where the ink and the music are not as separate as they might seem.

Peter: Another noticeable feature in the new album is your use of a field recording as a musical foundation. How did that come about?

Avi: My partner and I visited the Toronto Islands near Snake Island last summer. There were some crashing waves when it was windy. It sounded beautiful and looked really beautiful, so I took a video and then used the audio track with a little delay on top of it. I play the gudok melody on top of it.

Peter: Do you have any specific plans for your subsequent work in 2025?

Avi: There's a tape label in Calgary that will do a tape release of Nocturne. I also have plans for another album in the spring.

Peter: Thanks so much for your insights, Avi!

Purchase Avi C. Engel's Nocturne (Soundtrack for an Invisible Film) from Bandcamp. Follow Avi on Bluesky, Instagram, and Facebook.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments