Andy and OMD are not working the nostalgia circuit, though no one would blame them if they were. Instead, they continue to release new music that fans and critics rate as among the best of their classics and they already have plans to spend a large portion of 2025 on the road.

Bauhaus Staircase, OMD’s latest album, and their recent EP, Kleptocracy, are both available through the band's website.

Michael Donaldson: I want to start with, you may be aware of this, I don't know, but a very close friend of mine owns Florian Schneider's Volkswagen.

Andy McCluskey: Okay.

MD: It's a long story how he acquired it. But he basically shipped it from Germany to Tampa, Florida, and it was already in great condition, and he drives it around like a Sunday driver.

AM: What a great Sunday car to have, huh?

MD: I know, but he's afraid to drive it around any other time. And it has been shown at a couple of car shows.

AM: Well, it's in the right climate now.

MD: Yes, with Kraftwerk bellowing out of it, and I think he's even won some awards with it.

AM: Oh, I'd love to see that. That would be fantastic.

MD: That brings me to another thing. This is a story that I've related to a lot of people. I was having an under-the-weather day and decided to watch two BBC documentaries back to back for four hours of sitting on the couch and enjoying myself. The first was "Krautrock: The Rebirth of Germany," and it ends with Kraftwerk basically about to take over the world.

As soon as that ended, I started "Synth Britannia," which begins with Kraftwerk playing Liverpool. So it was funny watching those together because it was like one four-hour documentary leading to this.

AM: I mean, essentially, Krautrock led into the British synth explosion of the late seventies and early eighties. So they they belong together.

MD: Absolutely. And, of course, you had the moment of seeing them in Liverpool as a life-changing moment for you and Paul.

AM: Now, Paul wasn't allowed out by his mother. Paul was only fifteen.

MD: Oh, it was just you?

AM: Ha ha ha, yes. He's been so pissed off about that ever since.

MD: So you dragged him along into the cult of Kraftwerk.

AM: It effectively became a symbiotic relationship. I would go to Liverpool on Saturday morning with my paper round money and buy German imports, usually Kraftwerk, from this one rack of 12-inch vinyl in Probe Records in Liverpool, which was Liverpool's cool shop.

And then, I would come back to where we lived in a suburb on the other side of the river. Paul, who was studying electronics and an electronics geek, had built a stereo for himself. I only had my mother's old sixties mono record player, so Paul had a stereo. So that was it. I had the records, and he had the stereo.

That was how we started listening to music together in his mum's house on a Saturday afternoon when she was at work. And then we took the next crazy step to say, wow, could we make something like this? Of course, we couldn't because we didn't have any money. So we were playing my upside-down bass guitar, and he cannibalized some of his auntie's radios for the circuits and made these weird noise machines that we used to call noise machines.

We were very noisy and ambient for the best part of a year until we finally got an electric piano and an organ.

MD: What brought you to the German imports? How did you discover those at a young age?

AM: I think, like many English teenagers in the seventies, I was looking for something new, something different. I wanted something that was mine. I didn't want something that reflected what I perceived as Anglo-American rock clichés. And, of course, if you're going to avoid Anglo-American rock clichés, then you discover Kraftwerk. And I heard "Autobahn" on the radio in the summer of 1975. It was everything I could have wanted.

It was new. It was different. It was musical to my ears. I thought it sounded fantastic, but it was completely different from everything else I'd ever heard before in my life. And so that was it. I then started going and buying their records. And then, when I exhausted all the ones of theirs that I hadn't previously purchased, I started buying La Düsseldorf and Neu! and Can and all the various other German bands. This fulfilled my search for something new—music that was different.

I think that for a certain type of teenager, it's different now because we're in the postmodern cultural world, but at the time, everything was perceived as linear. This is in fashion; therefore, that's out of fashion, and then the new fashion becomes old-fashioned, and something new takes its place.

I was looking to define myself by the three markers: the music, the haircut, and the clothes. And Kraftwerk was my music. I liked a few other artists, but again, they were towards the more interesting end of the spectrum, people like Bowie and Roxy Music and Brian Eno and the Velvet Underground.

I mean, quite frankly, outside of my German bands and those I just mentioned, everything else was shit as far as I was concerned. (laughter)

MD: It was a similar experience for me because I grew up in a little rural town in the middle of Louisiana.

AM: You lucky boy. (laughter)

MD: Yeah, and I just had to find any music that was the opposite of what everyone around me was listening to. And for me, it was punk rock for a while. And then I happened to, in a record store, meet a guy who had this amazing record collection. And he was the one who was like, "Oh, check out this band Faust," you know, "take this home and listen to it." I was hooked on the German stuff from then on.

So here's a dangerous question, though, for someone from Liverpool, do you think Kraftwerk is the most influential band?

AM: Oh, I'm on record as saying that throughout modern popular music post–Second World War, Kraftwerk is the most influential band in the world. The Beatles were very, very, very good songwriters. And the journey they went on was quite remarkable. The changes in their music from the early poppy days to the kind of surrealist, acid-drenched later days were remarkable.

Essentially, it was still variations on an Anglo-American blues rock theme. On the other hand, Kraftwerk completely detonated all the clichés and did something new, as far as I'm concerned. And they heralded the advent of electronics in music, for better or worse—the computer and digital. So, as far as I'm concerned, Kraftwerk is the most important band in the history of popular music.

MD: You are on record.

AM: Good. (laughter)

MD: So, sticking in that period, who was The Id?

AM: Ah, The Id. Paul and I have known each other since he moved to my school when he was seven. We were in different academic years, so we knew each other but weren't close friends. And then, one day, just after my sixteenth birthday, he and a bunch of his long-haired hippie friends came knocking on my door, And I recognized him; I didn't know the others because he went to a different secondary school to me after the age of eleven.

He said, "Hi, listen, these are my friends. They've got a band, and they're looking for a bass player. I've seen you walking around the park with a bass guitar." Which, you know, doesn't everybody, you know, I just bought a bass guitar with my birthday money and went to a secondhand store with all the money I could scrape together.

And I brought this bright red Wilson Rapier bass. And, of course, I was walking around the local park. "Oh, hi. Yeah. Yeah. How are you? Oh, my bass. Oh, you noticed I've got, yes, that's my new bass guitar. I've just got over my shoulder. Yeah, you noticed it. Yeah." As you do! (laughter)

So he'd seen me and his friends come knocking on the door. And so his friends were in a band, and I started playing bass with them. Two things then happened. One, They realized with me singing backing vocals that I was better than their current lead singer.

MD: Oops.

AM: So they asked me if I would take over on lead vocals, and I said, well, you have to tell Graham that he's no longer in the band. He's your mate, not mine. I'm not telling him.

But also, I think because they lived a few miles away and Paul lived very, very close to my house, Paul and I would spend time together on Saturdays if we weren't rehearsing with the band because we very often couldn't afford to get together the £1.50 to rent the room above the library on a Saturday to rehearse.

And so Paul and I started this interest, as I said, in electronic music. Once he got some keyboards, we decided to put him into the band, and that's when it got properly named The Id, and we played a couple of gigs. I and my then girlfriend, Julia Neal, and my old friend, also on vocals, John Floyd.

It was pretty kind of fun seventies prog rock. But Paul and I started writing the songs because the band had a drum kit and two guitarists. They tended to make our music sound more conventional than we would have wanted. But we had no option until a few years later when everybody else attended university. We got the courage to get rid of them, get a tape recorder to replace them, and do it the way we wanted it to be in October of 1978.

And that was when we started Orchestral Maneuvers.

MD: You've known Paul since he was seven, right? I'm always fascinated by artists who have been in a working relationship with each other for that long, like for over fifty years for you two. What is that like? I can't imagine being in a continuing working relationship with my good friends from when I was ten years old.

AM: No, it is strange. I'm not close to any other friends I was at school with, but Paul and I, because we started the band, we started making music together when he was fifteen and I was sixteen. And then we started the band a few years later. We're very different people. It's not always plain sailing.

We've had our disagreements. The band split up from 1990 to 2006.

MD: Right.

AM: When we fit together, we bring what the other doesn't have to the table. Paul is an incredibly gifted musician. He's a brilliant writer of melodies. He also knows more than I do about musical theory, which is good.

He's much more technically gifted and patient than I am. So he does the mixing. On the other hand, I am full of intensity and ideas. I was going to do a fine art degree. He was going to do an electronics job. There's a difference between us, but it fits together. So, I guess I was just blessed. The one great thing about Paul, which was fortunate for me, was He was a very, he still is a very creative musician, but he's not overly precious or egotistical.

So, he would allow me to make whatever I wanted out of his and my ideas. It was a double blessing for me. We have also joked that we are different characters, and two Pauls would get nothing done, and two Andys would kill each other. So, you know. (laughter)

MD: I've read your nicknames for each other, the butcher and the surgeon.

AM: Yes, they hold up.

MD: So, the fine arts degree you discussed. As a painter, what was your craft within fine arts?

AM: It was, yeah, by the time I got old enough to apply to university, it was more sculptural installations and conceptual. I was fortunate to pass my A-level art and end-of-school art exams.

I wasn't particularly gifted with drawing. The painting I did used a lot of cut-up bits from magazines and newspapers, which they decided wasn't legally allowed. I wrote my thesis about Dada in the style of Dadaism, which made it largely unreadable. So I scraped through with the lowest grade you can get, which is an E pass. (laughter)

MD: Man, you were ahead of the curve on AI generation there, weren't you?

AM: I was trying to be my difficult self. So yeah, I got a place at Leeds to do sculpture. I chose Leeds because they had a recording studio as well. So I could do audio installations as well. I took a gap year when Paul and I started Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark in October '78.

I have subsequently discovered that had I gone to Leeds, on the same course, at the same time, would have been Green Gartside, the lead singer of Scritti Politti, and Dave Ball and Marc Almond, who created Soft Cell, we would have all been there. And I jokingly asked Marc Almond last summer when we were doing festivals with him if it would have been a supergroup or a superego clash.

And he went, "Probably the latter." And I went, "You're probably right." (laughter)

MD: I love the fine arts thing because that is a major part of the OMD aesthetic, like right from the beginning. Is Paul a part of that or is that your direction mostly?

AM: It's mostly mine, if I'm honest. Working with Peter Saville, who was the Art Director at Factory Records, and then became the Art Director at Dindisc, the subsidiary of Virgin that we signed to.

Unbeknownst to us, Peter and I ended up accidentally at the same record company after Factory, which was brilliant. Peter said he enjoyed working with me because I understood what he was talking about. If he referenced futurists, Picasso, or pop art, I knew what he was talking about, so I had the frame of reference.

So generally, the artwork was, I would be more involved than Paul. Again, on the technical and mixing side, particularly these days. It's more Paul than me. I wouldn't claim to dare to go anywhere near doing a finished mix. I'll, I'll, I'll tinker with it once Paul's got it nearly done. But, yeah, the artwork has generally been my element.

And particularly recently, since we reformed much of our music, our titles and themes have been influenced by artwork.

MD: Yeah, I do know that being a teenager, seeing the records in the bins, I mean, this is pretty much the case with any of the Peter Saville stuff, really, but I used to describe it as almost like receiving messages from outer space, because here I am, this kid in Louisiana. I see these record covers, and I'm like, what is this?

And it was like the wonderful days of buying records without hearing them, just buying them because of the cover.

AM: Well, what an amazing thing it was. I used to take the train to Liverpool and come back on the train. I was sitting on the train with the sleeve, opening it up, looking at the artwork, pulling out the inner sleeve, reading the lyrics, reading the song titles.

And all of this in the sort of hour to forty-five minutes before I got it on the turntable, it was like record sleeve foreplay. You know, (laughter) before you got to the main event, you have already been absorbing the sleeve and getting so excited.

MD: Do you visit museums on tour?

AM: I try to when I have the energy. The older I get, the more I find myself a bit of a zombie on tour. I tend to sleep a lot when I'm not on stage, but I have been blessed to travel the world and go to all sorts of art galleries and museums when I've got a day off. There's nothing worse than if I haven't got a day off and can't go and see a gallery I want to visit, but it is what it is.

MD: Do you have any favorites?

AM: I'm a huge fan of MOMA in New York. I also love the Met and Neue Galerie in New York. I could spend a month going to art galleries in New York. Chicago has some amazing paintings as well.

MD: I have a past life as a touring musician. I used to go to art galleries, and seeing a work go from one gallery to another was always fun. Oh yeah? I'd pop into one gallery and see this work that I saw in an exhibition or gallery maybe a year prior, and it'd be like, oh, it's almost like running across an old friend.

AM: It's great, right? Because, of course, I mean, you know, galleries depend upon borrowing from other institutions for their big exhibitions. The downside is that when you go specifically to see a painting in a gallery, it's not there because they've lent it to another museum.

MD: Okay, so "Bauhaus Staircase." This record's great, but I want to get into what you mentioned earlier about the art's influence on the title, the lyrics, and such. And I looked up a description of the Bauhaus stairway, Oskar Schlemmer. There was a listing in The Guardian, and I'll just quote it quickly because I thought this was interesting.

It says, "The painting looks back at the Bauhaus as a utopia rooted in everyday life. These are ordinary modern young people. Hair and clothes in contemporary fashions, walking purposefully, intently. They believe in what they are doing. They have the rounded, simplified geometrical bodies Schlemmer created in his ballets as they ascend to the higher state of modern marionettes."

AM: Very good description.

MD: One thing I find great about that is that he's talking about people becoming robots. But, like Kraftwerk, it's a positive thing.

AM: Oskar Schlemmer, who painted the painting several years earlier, had done the incredible costumes for the Triadic Ballet. If you see them now, they're in the museum in Stuttgart, and if you see them now, they still look unbelievably crazy and futuristic, and they're now well over a hundred years old.

What was the title of the New Order song that that French dance troupe did where they were dressed like the characters out of the Triadic Ballet?

MD: Oh, "True Faith," I think, wasn't it? Wasn't it "True Faith"?

AM: Yeah. So yeah, I think so. I think you're right. Yeah. I mean, essentially, what Schlemmer is trying to do there is, for the sake of simplicity and clarity, to reduce forms to simple shapes.

It's reductive but beautiful. In no way is he suggesting that people should be robots or they should be minimized. All were reduced to robotic ways. As you say, they were young people exploring an interesting new future. The amazing thing about the Bauhaus art school is that from 1919 to 1933 when it was closed down by the Nazis, it was an applied art school.

It wasn't esoteric. It wasn't art for art's sake. It was a practical application of art for form, function, design, and architecture. And even so, the Nazis still shut it down. Totalitarian dictatorships are prone to do with art because they're scared of it. They don't understand it. They fear that it might be saying something they don't understand about them.

And often, it is. Of course, I called it staircase because "Stairway" was too soft. "Staircase" had a nice punch to the rhythm of it. It needed that second syllable emphasizing.

MD: You've referred to this as your political album.

AM: It has politics on it. We've been, we've been political before.

MD: Absolutely. Absolutely. But obviously, songs like "Kleptocracy" and "Anthropocene" and even "Bauhaus Staircase" in a way, which has…

AM: You're a lucky bastard. You're going to have a fucking president who's going to be a criminal. Cause this isn't going to stop him.

MD: You know what? Do you know who Howard Dean was or is?

AM: Yeah.

MD: Gee, remember when Howard Dean, all his presidential chances disappeared because he made a weird sound?

AM: The incredible thing now is that the, it's so brazen, the corruption, the narcissism. People used to do their dirty deals under the table. Now they're right on top of the table in broad daylight.

And people just seem to accept that that's how things are done now. It's utterly frightening.

MD: Yeah. I refer to it as a grifter nation.

AM: Yeah.

MD: I love the lyric, "I'm going to kick down fascist art." That might be my favorite lyric of the year.

AM: That one just came out. I was thinking about Bauhaus, and I was thinking about Nazis, and you know what, the funny thing is, don't tell anybody, I have a soft spot for fascist propaganda art.

The Russian posters and the Chinese…

MD: I am obsessed with Soviet art design. Absolutely.

AM: Would I want to live in one of those totalitarian states? No, but my God, the art. It was stunningly powerful and beautiful, but of course, you had more people like Malevich, who was one of the very first ever abstract artists, who had to go back to doing art that was recognizable, um, specifically figurative because otherwise his art would have been banned by Stalin and the communists.

So yeah, I want to kick down fascist art, and also, as well, it's the idea of toppling statues, which we saw, we've seen several times over the last few centuries of those. Dictatorship statues are being knocked down or put into statue parks to remind us of our history.

MD: You had mentioned earlier on this subject about art as something that the fascists or the authoritarians hate.

AM: It's not just fascists; it's such totalitarian communist regimes as well.

MD: Right. So, do you think art helps us maintain democracy?

AM: Good question. Yeah, go on, you, you, you tell me your theory.

MD: I think of creation as resistance. I tell this to a lot of my artist friends who are understandably upset about the state of this country and the state of the world, and they get depressed, and they've got horrible people living rent-free in their heads.

They don't create because it's just hard for them to do. Again, this is understandable, but my idea is to keep creating because creation is inherently optimistic. You're making something for an audience that does not yet exist for that piece. So you're thinking there is a future for someone to enjoy your creation, inspect your creation, or whatever.

Artistic creation in itself is an optimistic resistance. And to paraphrase something I read from Brian Eno that hit home, he recently said that it is one responsibility of an artist, if they choose, to envision worlds that we want to live in so that we can perhaps arrive there.

AM: You have a strong case. I mean, how effective it is in changing the world, I'm not sure that art Deals hammer blows against problem situations. However, it is very good for reflecting and engaging people to have an alternative mindset to what you might feel are situations that are not positive. That's, you know, why I love Dada; it was a response to the slaughter and horror of the First World War.

It was scary that some English vorticists and Italian futurists were excited about warfare; they thought, "Oh yes, this is going to clean the slate; it's dramatic and powerful and shattered and strong and engineering." Of course, what came out of it was that Dada went. If this is the future, if this is where technology leads us, we don't want any part of it.

If intelligent minds lead us to this, then let's be stupid. Let's go boing boong chack and da da da, and whatever, you know, because it's as nonsensical as that. as the sense that led us to the slaughter of the Great War. You see, it's been around for a long time through Guernica, and until now, you still get art that tries to guide us in a different way or at least say something about the status quo and ask questions about it.

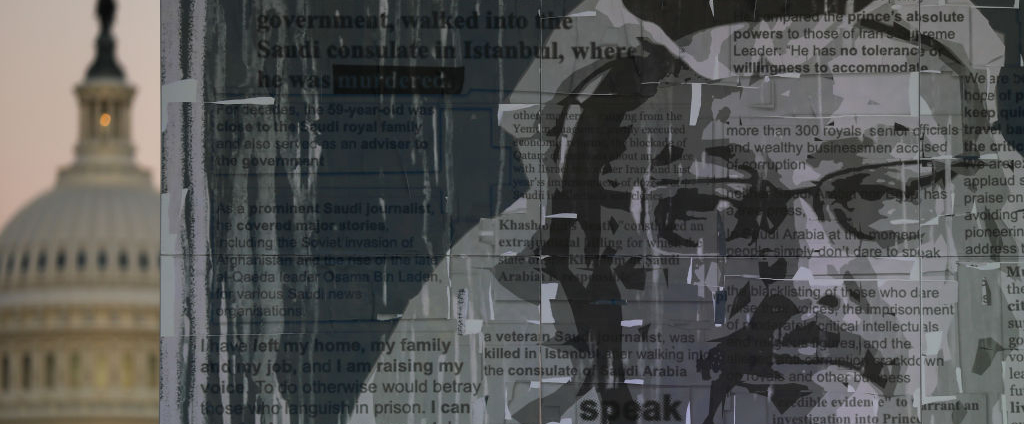

And I've been furious at, particularly at Trump and Boris Johnson, Putin, Saudi Arabia, you know, Khashoggi goes into an embassy and comes out a few days later in different bags.

And, initially, the world is like, "Oh, shocking, terrible, terrible. Oh, Saudi Arabia, how awful." And then they let the dust settle six months later, and they're like, "Anyway, uh, listen, we'd like some of your oil. Would you like some warplanes?"

MD: Again, the thing about Howard Dean is that he gave a speech and gave a crazy "woo." It was mocked everywhere and shown on TV a million times. And basically, that was the end of his presidential campaign. And it's like, how quaint, you know?

AM: Yeah. Yeah. And that Trump seems to luxuriate in all of his ills and wrongdoings. I think that it's hilarious that he's in court, and nobody is saying he shouldn't be president because he's having sex with hookers. The Kennedys weren't exactly whiter than white, but they weren't so brazen about it. It's scary that we've been so patently and recently led by people who are not politicians in the sense that they actually want to do something for other people.

MD: Yes.

AM: They're politicians who are just raging narcissists who want to be the president or the prime minister. The only difference between Boris Johnson and Trump was that Boris Johnson didn't want to do anything. He just wanted to call himself prime minister and then sit around doing fuck all and have somebody else do the work.

The scary thing is that Trump has many ideas he'd like to enact when he's president, which just worsens the world. And he's already given you the poison chalice of the Supreme Court, and that was just in his first term.

MD: All right. Time to call my therapist.

AM: Yeah, me too.

MD: On that note, um, "Kleptocracy" is the happiest song about all these subjects I can imagine.

AM: Did you ever hear "Enola Gay"? (laughter)

MD: Yeah, yeah, exactly. There is history that I'm sure you're mightily aware of, going back to "Enola Gay" and all those serious messages in danceable songs. It's this idea of not necessarily hiding the messages.

It's almost like a movie that covers these really serious subjects but does it in this entertaining way that not everyone picks up on it, but some people do, and it gets under their skin in a good way. Is there any tension in what you're doing toward that with these songs?

AM: There was no conscious endeavor when I wrote "Enola Gay" to sweeten the pill. After the event I've talked about, you know, if you try to be overly didactic, one, you end up making shit music because the lyrics don't rhyme properly, or there's no melody or anything. You're just beating people over the head with your words like a sermon. And secondly, yeah, it's a lot easier to get the medicine down if you put some sugar on it.

But it wasn't conscious. It honestly was not conscious. Some people were quite horrified when "Enola Gay" was released. They said, "Hang on, how can you have such a jaunty tune about something so terrible?" And I was like, "Yeah, I didn't intend it to be that way, but it works."

Because my fallback defense invariably was like, "It's not as weird and fucked up as naming an airplane after your mother and then dropping an atom bomb and killing 150,000 people. That's fucked up." (laughter)

MD: Yeah. So then the "Kleptocracy" mentions a journalist's torture and dissection by Saudi Arabia.

AM: Oh, Khashoggi, yeah.

MD: Yes, Khashoggi. And it's the happiest song about something horrible I could think of.

AM: Because I found, as I say, obvious moralizing can be very clunky and ineffective, I have often preferred to couch my feelings and ideas in metaphors, which sometimes can cloud them to the point where people don't understand what the hell I'm on about.

And there are millions of people to this day who don't know what "Enola Gay" is about. But it was an opportunity at least to put the peg on the wall, hang the ideas on it, and discuss it using the song as a kind of leader. I think apart from Khashoggi, I won't name the other names, but you know, you know who I'm talking about with dirty slogans on the red bus door, the exits, and the disinfected beds. (laughter)

You can sit down with a, with an idea about where you want to go and what you want to write. But in the end, when you're making a piece of art, I'm sorry if I sound egotistical and big-headed, calling our pop music art; to me, it is. So I'm sticking with that. It takes on its own life, you know, and sometimes it goes off in a direction, just go, holy shit, didn't expect it to go this way, or this is not what I'd intended, or this is, this doesn't seem to be what I wanted to say, but you know what?

It works better this way as a piece of music, so I have to go with the flow.

MD: When I listen to music, I'm not like someone who picks up on lyrics right away. I tend to sort of listen to music as a whole. And I'm listening to this song, preparing for this interview, and I'm like, I should check out these lyrics.

And I look at the lyrics, like, "Oh my God, a lot is happening here. I had no idea what was happening in this song."

AM: I mean, "Kleptocracy" was kind of a giveaway in the title. (laughter)

MD: Yeah, absolutely.

AM: For those who don't know, it's the rule of thieves.

MD: Yes.

AM: Or being ruled by thieves.

MD: Right. When I was a kid, there was a band that I liked called the Minutemen. They were funky and fun, but the lyrics were often metaphors and things they would throw about political events of the mid-eighties and things happening in Central America.

And I remember being such a fan of the band that I wondered what they talked about. I would like to look it up, research it, and figure out what the band was talking about, which shaped me a bit regarding how I think about the world. So I think there is something to doing that. And in a way, that's…

AM: I think so.

MD: Yeah. And in a way, like you said, that's not hitting you over the head. The remarkable thing about "Kleptocracy" is that it's catchy and jaunty. It's even a song you can sing along to, but it has this very pointed message. I think that's cool.

AM: Thank you. Well, then, it's working.

MD: And another thing that I think you balance well with Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark in 2024, without naming names, there are a lot of bands that have been around for quite a while who either update themselves, their sound. I don't know if they're trying to go for the kids or what they're trying to do, but they just don't sound like themselves anymore.

They just become kind of homogeneous. Then you also have other bands that try too hard to sound like they did, and then it just sounds very retro and nostalgic.

AM: Yeah, it's like a pastiche tribute band of themselves.

MD: Yes. And what I love about what you and Paul are doing with this album and the last bunch of albums is that you somehow balance in the middle to me.

Very few bands have been around as long as you guys that can effectively do that. I think it's very remarkable that it doesn't sound retro, but it sounds like OMD if you catch what I'm saying.

AM: Well, then again, we're hitting our mark. One, we were determined that if we were going to release new music, it would be good. It had to be strong lyrics, strong melodies, and strong ideas. Both of us continued to make music after the band split up, and we learned new studio and programming techniques and computer programming techniques. So we had a handle on how to make modern music. We weren't locked off in our ivory tower back in 1983.

I think we were both able to employ those elements. But when you get to a certain age, and you've made thirteen or fourteen albums, it's really hard to come up with new ideas. It's hard to come up with a melody you haven't done before or a beat that doesn't go, "Oh, that's the same drum patterns, blah, blah." So you have to work hard at it.

And I like to think that more than anything else, hard work goes into it. It's not just like, "Yeah, yeah, we went in the studio and threw together the first ten things that came, and the good, the bad, the ugly, there it is. There's a new album. And it sounds like us because it is us."

The tunes aren't good enough. The lyrics aren't good enough. And I think that a lot of bands, as Paul likes to say, release a new album because they need a logo for the latest tour t-shirt. (laughter) Not because they want to make new records. They just need a new brand for this year's tour, you know?

And I think, sadly, that's the case. I'm not going to name any names. There are contemporaries of ours and other bands who I just listen to, and I go. It just sounds like somebody is doing a pastiche of your earlier work. It's not fresh. It's not exciting, but yeah, it sounds like you guys, but it's nothing I want to hear.

There's nothing new to me. It was important for us to do something that we felt was functioning in the modern era and that wasn't just, you know, trying to sound like OMD. We will sound like OMD because Paul and Andy are writing music together. We are proud of how we used to make music because we didn't know the rules when we started out.

We weren't even consciously trying to break the rules. We didn't know them, so we did our own thing. "Oh, that sounds all right." And people subsequently said, did you realize that you were doing this, and then you had a diminished fifth or something, and finally, the course, you put the fifth note on it and completed the chord.

I'm going, "Really? Okay. I had no fucking idea. Thanks for that!" (laughter) We just said we would sound like us when we got back together. But we will make sure that it's quality because, over the years, we started swimming against the tide. Then the tide caught up with us, and since we reformed, we've stopped being the forgotten band of the late '70s and '80s, and people say lots of nice things about us, like we're Iconic and influential.

And so finally, when we feel like we've got a place in the pantheon recognition, the last thing we want to do is make shit records, and people go, "Yeah, great band, but don't bother listening to any of their new stuff. It's shit, you know? And if they play it live, just go to the bathroom." (laughter)

MD: Yeah. And I think people appreciate that, too. I love this quote I saw from you, "Playing a hit single is not like going to the fucking dentist." (laughter)

AM: I never understood why bands moan, "Oh, I'm so bored playing that song." Oh, what? The song that got you all the money? The song that's still played on the radio? The song that everybody loves, and you want not to play it or even worse: Do a stripped-down acoustic version at half speed?

Have some fucking respect, you know?

MD: You're finding a lot of new, younger fans when you play now, right?

AM: We are. And it's down to a couple of things. You know, we alluded to this earlier, this kind of postmodern era where nothing's in fashion, therefore nothing's out of fashion. And if you're considered seminal or iconic or just of value within a particular genre, Then people will find you, and there's always a new generation of young people who get into electronic music because it's generally the most interesting music being made.

You can do only so many things on a guitar, bass, and drums. In contrast, computers, synthesizers, and samplers give you a much broader palette to explore. And I think younger bands have credited us as influential, so their fans have discovered us. People go down wormholes on YouTube and, you know, iTunes and if you like this, you'll like that.

And yeah, it's fantastic to see the age demographic changing. It's wonderful.

MD: Yeah. I have friends who work in record stores, and I used to have a record store back in the early nineties when it was very tribal. You only bought your punk rock records. You only bought your dance records.

And I have friends who work now and say, you can't predict what anyone's going to buy because it's just, it's all over the place. It's like really nuts. Younger people now have no genre restrictions, which is cool.

AM: It used to be, you know, if somebody walked into a record store wearing these clothes with this haircut, you'd go, "He's gonna buy The Cure." Or, "He's gonna buy John Mellencamp," or he will buy some…

MD: Right. When I used to have my record store right away, from someone walking in the door, I could be like, "Oh, you want to hear this new goth band? You might like them. Check it out." One thing that blew my mind on this subject is my ten-year-old niece.

She was visiting a couple of years ago. And I asked her what music she was listening to, and she started naming off stuff, and then she said, and I like this band, Prefab Sprout. I was like, what? (laughter) I talked to her mom—my sister-in-law—and she was like, yeah, she's discovered them on a TikTok video or something.

And now she's really into them.

AM: How music gets regurgitated to the next generation is remarkable. Yeah, because something gets picked up and used on social media, and they don't know where it came from. But again, it doesn't sound out of date because nothing is out of date anymore. In the early '80s, something recorded in the '50s sounded like something twenty-five years old.

But now people are consciously trying to sound like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Buddy Holly, Led Zeppelin, or whatever; it's just atomized.

MD: Well, thank you so much for this.

AM: Thank you. Great questions. Interesting.

MD: Oh, excellent. Thank you. And one last thing. I have another interview in two hours with David J, formerly of Bauhaus.

AM: Oh, you're kidding me. Wow.

MD: I'll get some Bauhaus synergy here.

AM: Yeah, well, I'm expecting Bauhaus Reformation with a song called "OMD Elevator," okay?

MD: Yes, I will; I'll suggest it. (laughter)

Comments