Sound waves carry an ancient Persian homoerotic poem through a converted hammam in Istanbul, an invisible act of resistance in a conservative neighborhood. This intersection of preservation and protest defines the work of Başak Günak, who splits her time between Istanbul and Berlin, creating music and sound art as AH! KOSMOS. Her album Rewilding on Subtext Recordings builds from her sound installations, folk songs, and experimental instruments to explore how spaces hold memory and enable change.

Rewilding showcases Günak's expansive artistry, which includes recordings on Compost and Denovali Records and installations at the Barbican and Gropius Bau. The album's eight tracks bring together disparate elements: a rare Haldurophone, fragments of Anatolian folk music, and sounds from her installation work about cultural memory and resistance. Much like its ecological namesake, Rewilding creates new sonic possibilities while honoring what came before.

Lawrence Peryer: Tell me about the role of location and physical space in both the final recordings on Rewilding and how place might shape the compositions as you record.

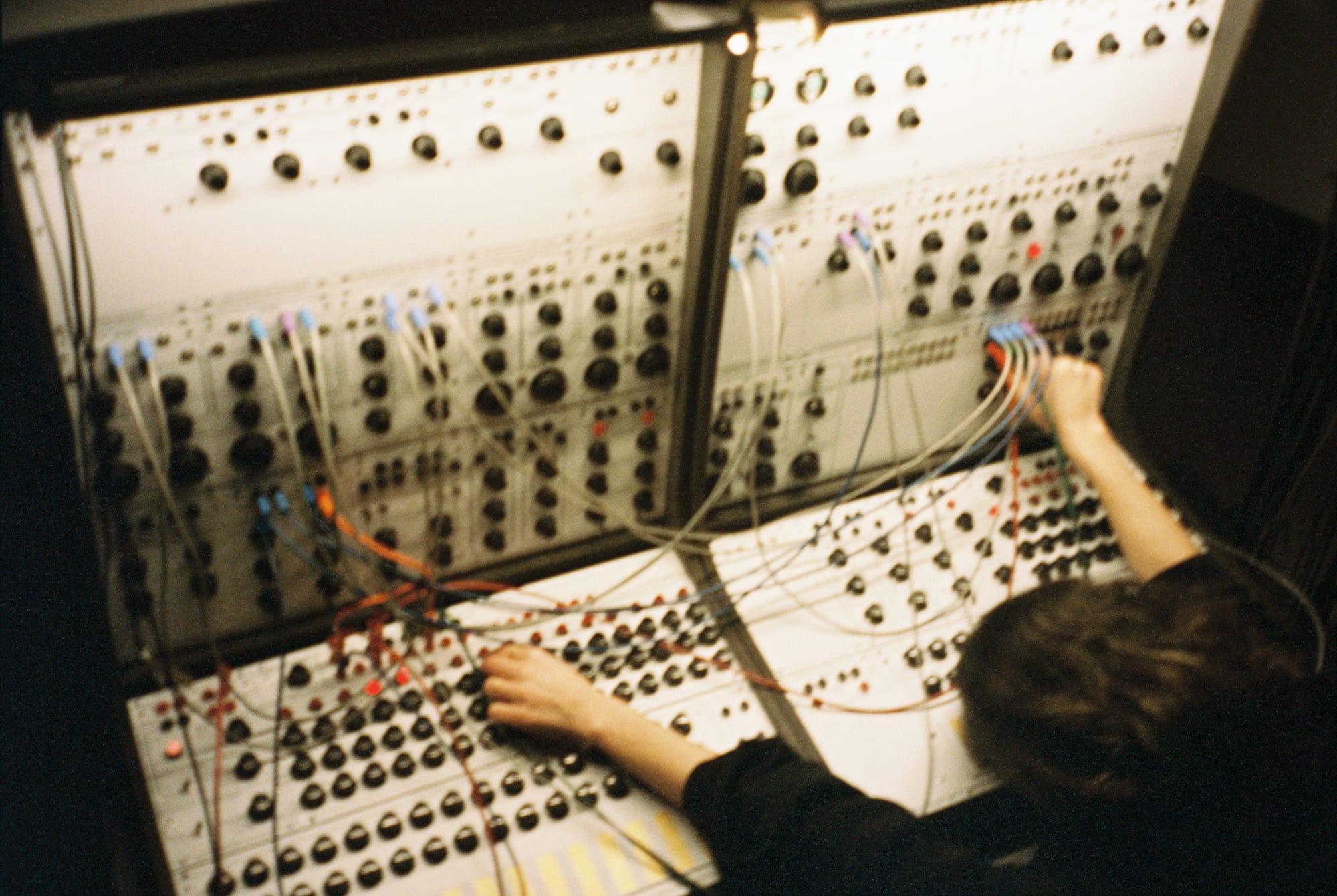

Başak Günak: Most of the songs were part of my sound installations or hybrid performances that I did over the past five to seven years. I wanted to revisit the songs and make derivations from them. Through that process, I visited many interesting studios and recorded special instruments that each studio had. The different feelings of the cities' soundscapes and having that variety of instruments were important to me.

Lawrence Peryer: Did you know that you would encounter different instruments, or did you choose the places because of what they had?

Başak Günak: I was in different places for different reasons. For instance, I was in Stockholm for a residency at the Electronic Music Studio. There was a Haldurophone in the residency, which I had loved for many years. I was in touch with the instrument's inventor, Halldór Úlfarsson, and had been trying to find that instrument. Learning that I could use it while I was in the residency was an amazing opportunity.

Lawrence Peryer: Site and location are important, especially your installations. Could you discuss the meaning of spaces and architecture or how location seeps into your work?

Başak Günak: It might be good to talk about this through one of the songs, "Foraging," derived from an installation of mine. The concept of that piece is a terrible thing that happened in the nineties in Southeastern Anatolia during my childhood. I wanted to work with an Anatolian folk song and deconstruct it. The whole installation was built on that idea—the sound gave the region's topography in the space, making the space recall the landscape of that area but also singing the place and its story.

Folk songs that belong to that place reflect its trauma and melancholy. It was a bit of an internal ritual. We sang with the creative performers, and the next day, the eleven speakers gave the soundscape using what was recorded. It changed from performance to installation. I reworked that piece, made it into a new composition for the album, and made it even more layered, like the story of the space and the story of that area so it could introduce itself.

Lawrence Peryer: What is your hope for a piece like that? Are you looking for healing and remembrance?

Başak Günak: I'm interested in the memory side of it. Through sound, you are recalling the memory of that region or space. Is it healing? Who knows. It can be, but it is more of a memory recall.

Last year, I made a sound installation in an ancient hammam. Some tiles in that hammam contain a homoerotic poem written in ancient Persian. This hammam is in an area in Istanbul that is very conservative and homophobic. The sound in itself is resistance because you cannot make a visible queer work in that hammam right now. It is subtle, but with sound, you resist the current situation.

Lawrence Peryer: It sounds like your different projects or works are almost in dialogue with each other—composition and music, sound installations, theatrical and dance contexts—and the work is always shifting.

Başak Günak: It took time for me to understand how my work weaves together. I'm doing this piece and that piece, but over the years, I started to understand the topics I'm drawing from, and they started to make a bigger ecosystem for me. I began to understand how to read "Bastards" from my very first album in combination with "Swamp" and then "Rewilding." They made sense in a bigger ecosystem.

Now, I see the bigger picture and feel what attracts me and what puts me at ease. I realized that I'm not changing concepts so much; I'm in one bigger ecosystem, just changing sometimes the mediums through which the work appears. Sometimes, it doesn't even appear; it's just part of the research.

Lawrence Peryer: It almost sounds like it's one work that manifests itself in different ways over time, and with the benefit of time, you can look back and see it that way—like it's one organism that takes on different forms, depending on what you're doing or where you are.

Başak Günak: Yes, it starts to feed itself. When some ideas attract you, you begin to understand why you're getting pulled to those topics on a personal level. So, not just on the professional side but also on the individual side, it creates a bigger dynamic where things feed into each other. The spaces where this happens change—sometimes on an album, sometimes as an installation.

Lawrence Peryer: What things influence you or set you in a direction the most? Is it literature? Current events? Philosophy?

Başak Günak: Since beginning my journey, I've been interested in social and cultural studies. Current events also influence me. Around 2010, before my first release, I attended lectures in Istanbul that inspired my work from different angles—from art criticism to philosophy to literature. I'm very drawn to Georges Bataille on the literature side, but through Rewilding, I'm also pulled into anthropological studies, such as Anna Tsing's writings and approach.

Lawrence Peryer: The concept of rewilding has some fairly specific connotations. What does it mean to you? And how does it play into some of the choices you make sonically?

Başak Günak: Rewilding is a major theme in anthropology related to damaged ecosystems. Through sound, I was thinking about how we can introduce that concept. It's very abstract, of course, and how to execute this is a question that guides me through my work.

Whistles, murmurs, and breaths are qualities that I use in sound installations to recall the memories of those stories. It brings the decay to sound, and I was excited that both the whistling and non-whistling—the breath that comes out when you cannot whistle—were interesting. It creates specters in the field, and I like that aspect of it.

Lawrence Peryer: When you're working on a project, do you ever find that you have to abstract it because it's too literal? I've talked to people who have said they had to throw things out because their intention was coming through too clearly, and they needed to make it mysterious or leave something for the listener to interpret.

Başak Günak: No, not with these concepts. I think I'm even aiming to make them clearer. I've started to write and talk more about the work. However, the songs often have different meanings, and I prefer to keep them abstract and not limit how they exist in the world. I like how they float, releasing them from the bonds where they were initially created.

With "Rewilding" or "Swamp," these concepts are already mysterious, opening up lots of space for us to imagine them. So, I don't feel fear about being concrete about them.

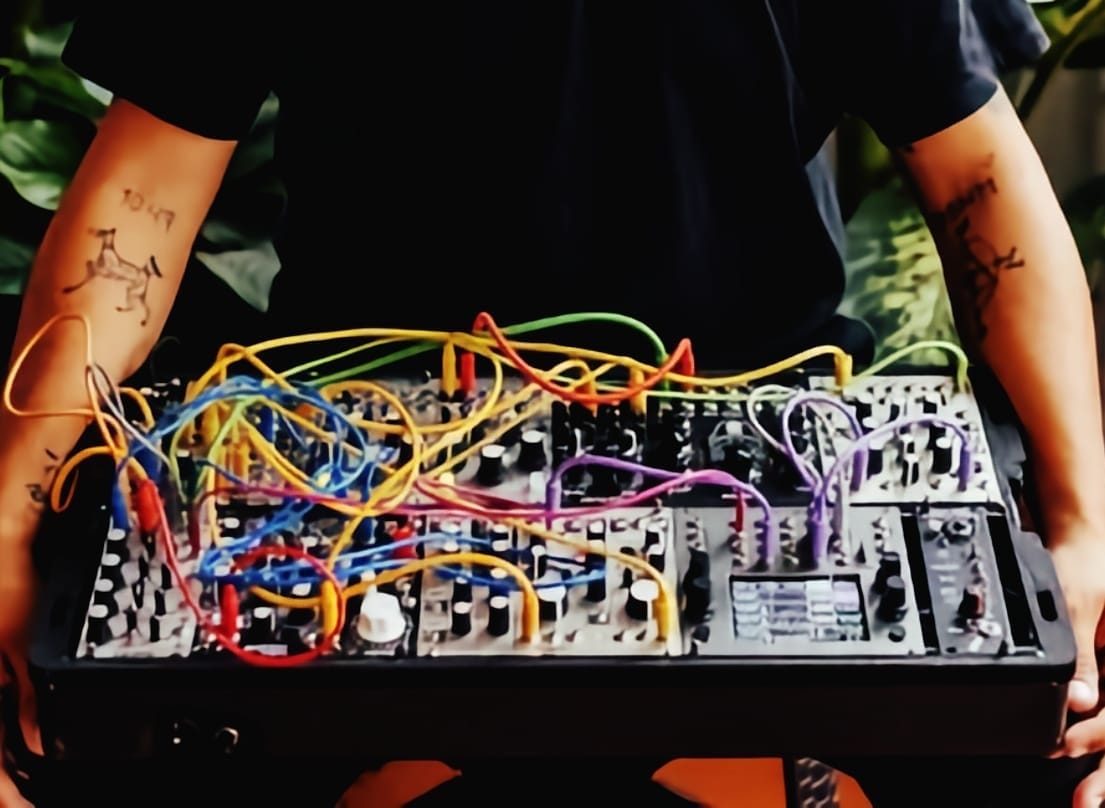

Lawrence Peryer: Because your music moves between structure, composition, and experimental sound design, I'm curious—is it all composed in advance?

Başak Günak: I don't work with written music. I work with different improvisation methods, and the sound itself is already part of the process. I don't sit down and say, "Now we are doing sound design." The songs in Rewilding were already meant for something, so I tried to excavate the work to take out that meaning, and the method became the way to make it happen. Which method helps that excavation is unknown. Sometimes, it happens very quickly; sometimes, you're just waiting for the last meaningful layer to come, and you don't know when it's coming. You just have to show up.

Lawrence Peryer: It's almost like a craftsman's approach to it—you just have to show up for work.

Başak Günak: Yes, and the album-making process is different. I'm not just gathering sounds and putting them together. It has to create a meaning. Sometimes, they're missing one part, not as a song, but as a meaning that's revealed on the album, even when there's a concept.

Lawrence Peryer: Foraging is an interesting word, especially sonically. It implies so much about the process and joy of discovery. It could also mean coming up empty—sometimes, when you go forage, there may not be any discovery that day.

Başak Günak: Exactly. What also drew me to foraging is that it doesn't require exclusive territory. I find this territorial limitlessness interesting. Although abstract, it resonates with ecosystem dynamics.

Lawrence Peryer: Were you trained as a musician in your artistic development, or did you come from a fine art background?

Başak Günak: I don't usually call myself a musician—it's an identity that I generally reject or embrace depending on the situation. I didn't study fine arts or music until my master's degree in sound. Before that, all my education was based on science—I studied chemical engineering. I was a self-taught bass player and slowly learned sound engineering in my master's. I also studied composition with a very important choreographer, Işıl Çakmak.

Lawrence Peryer: Are you primarily based in Berlin now, or are you still in Turkey?

Başak Günak: I'm still rooted in Istanbul and working there a lot. But my base is now in Berlin, and I also go to Stockholm regularly. I like that floating way of being. My studio is in Berlin, but I don't want to lose my connection to Istanbul because it's so important to me in many ways.

Lawrence Peryer: Given that the work that became Rewilding is drawn from your art installations, do you present it live?

Başak Günak: Yes. I already have an idea of how to present it. I've already done it without calling it "Rewilding," actually. I tried it before the album release. Songs must get outside through different areas before appearing on an album, and that helps me solve situations between the songs, whether in small or bigger events. I've performed it solo in the past and also with collaborators. I'm planning to keep it in that form, and there are more layers that I would like to explore as well. There will be more to come from that.

Visit Başak Günak at ahkosmos.com and follow her on Instagram. Purchase Rewilding from Bandcamp or Qobuz and listen to it on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments