In 1980, an eighteen-year-old Jewish kid from Milwaukee's North Shore suburbs snuck away to visit New York City. Michael Dorf told his parents he was headed to Madison but instead flew to LaGuardia, where he met his girlfriend in Greenwich Village. The city reveals itself with possibility, a place where the invisible threads of Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Reed weave through concrete and fire escapes. Seven years later, with $13,000 in savings, Michael opened the Knitting Factory, an experimental venue on Houston Street that would transform the independent music landscape in New York City.

The story of Michael Dorf's career reads like a history of the alternative music scene itself. From the yellow-painted walls of the original Knitting Factory—where he hung sweaters from the ceiling to hide ugly tiles—to the elegant interiors of City Winery venues across America, Michael has consistently created spaces where music, community, and sensory experience interact. His early digital music ventures with Apple and Intel preceded the streaming revolution by years. His venues have hosted legends from John Zorn to Lou Reed, with the latter becoming both a performer and a friend who shared Michael's growing passion for fine wine.

Twenty years ago, Michael launched one of his most enduring legacies: the "Music Of" tribute series at Carnegie Hall. What began as a Joni Mitchell celebration has evolved into an annual tradition honoring musical icons while raising over $2 million for music education programs. Each March, a constellation of acclaimed artists gathers to interpret the honoree's work, creating unique moments and illuminating familiar songs in surprising ways. Michael has orchestrated these exchanges with the precision of someone who understands that cultural experiences are holistic enterprises, engaging all the senses simultaneously.

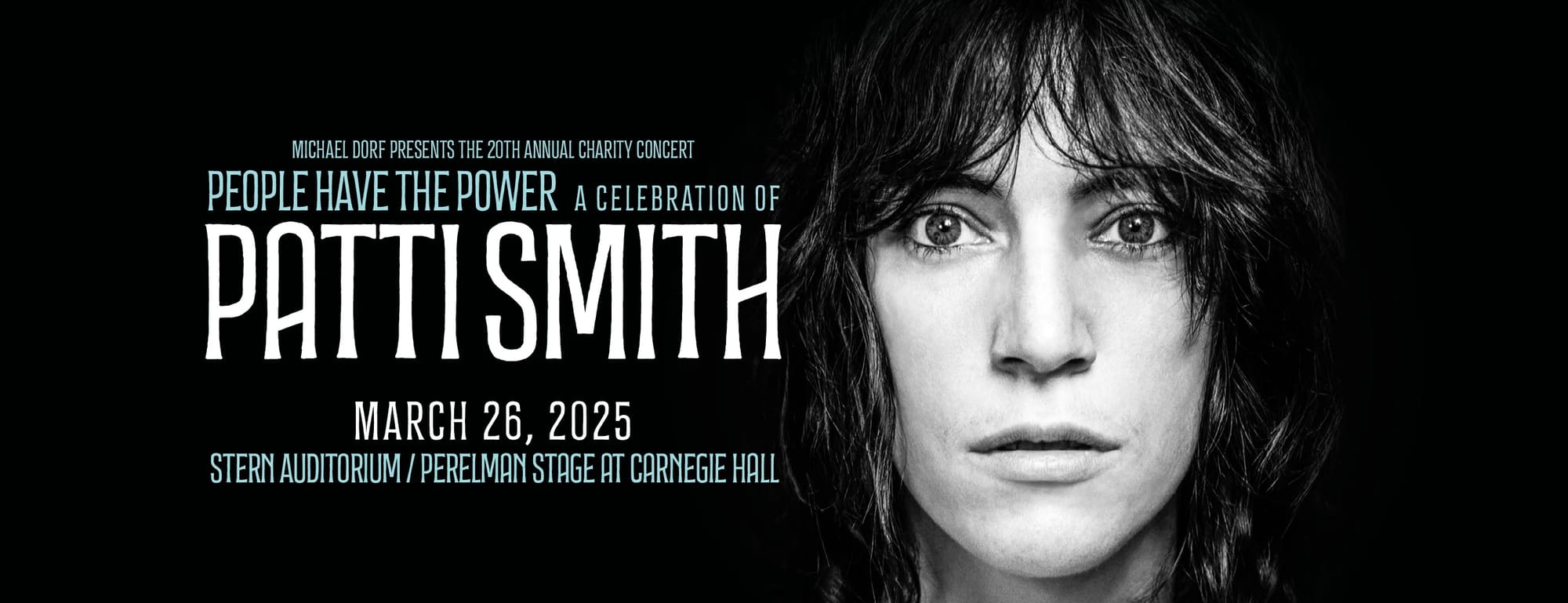

For the series’s twentieth anniversary, Michael has secured a lineup to honor punk poet laureate Patti Smith, including Michael Stipe, Chrissie Hynde, Karen O, and other luminaries. The house band, led by Tony Shanahan from Smith's ensemble, features all-stars like Flea, Charlie Sexton, and Steve Jordan. The occasion represents the culmination of years spent convincing her to accept this honor. On March 26th, something extraordinary will unfold at Carnegie Hall, another chapter in an ongoing conversation between artists and audience, past and present, origin and influence—another strand woven into the fabric of a city that continues to make space for beautiful collisions.

Lawrence Peryer recently hosted Michael Dorf on the Spotlight On podcast, a meaningful occasion for the former Knitting Factory regular. The two discussed the earliest days of the Knitting Factory, how a risk that paid off led to twenty years of Music Of concerts, and the challenges of organizing the Patti Smith tribute at Carnegie Hall. Michael also reveals his wish list for future Music Of tributes and tells a great story about the late Sonny Sharrock. Listen to the entire conversation on the Spotlight On player found below. The interview transcript has been edited for clarity, flow, and length.

An Eclectic Factory of Arts

Lawrence Peryer: I know we're here to talk about the Patti Smith tribute show, but I'm hoping you can indulge me in a couple of minutes of origin story.

Michael Dorf: Sure, absolutely.

Lawrence: What initially brought you to New York from Milwaukee? What were you chasing?

Michael: It actually connects to Patti in a way. That artistic New York scene built around Andy Warhol, Lou Reed, the Jack Kerouac Village vibe—I felt a natural magnetism toward it. When you're growing up in the white North Shore Jewish suburbs of Milwaukee, it's as safe and idyllic as you can get.

I once snuck to New York when I was 18 to visit a girlfriend. I told my parents I was going to Madison, but instead flew to LaGuardia and met my girlfriend in Greenwich Village. We went to Washington Square Park, had pizza, and got high. That was probably 1980, and something magic about New York appealed to me.

The lore of Allen Ginsberg, the beat generation, On the Road—more than anything, I wanted that. So when I opened the Knitting Factory in February of '87, Wednesdays was poetry, Thursdays was jazz, and weekends were rock and everything in between. I wanted it to be this eclectic factory of arts.

Lawrence: Did you have exposure to avant-garde and experimental music before opening the room? I'm curious where you were musically.

Michael: My friends played Beatles, Zeppelin, and the Doors. At a Jewish socialist camp in Northern Wisconsin, I was exposed to Dylan, Pete Seeger, and Woody Guthrie. I liked jazz, though I can't tell you why. By college, pre-Knitting Factory, I loved bebop and Miles Davis and was getting into Pat Metheny, Ornette Coleman, and the more experimental stuff like King Crimson.

I knew of the Lounge Lizards, Philip Glass, and Laurie Anderson but wasn't coming to New York to connect to them specifically. I wanted to bring in whatever wasn't happening at the Village Vanguard and the Blue Note.

Lawrence: What was your thesis around the Knit? Were you thinking, "This is going to be an incubator for freaks," or "I want to be surrounded by art"?

Michael: I was 23 with no family. I was fortunate that if the $13,000 I invested went away—which was from my bar mitzvah and beer can collection—I could go back to Wisconsin with my tail between my legs.

It started because I wanted to be a record company guy, but that immediately failed. I couldn't get anyone to buy the records. Then I found this old Avon office on Houston Street and thought, "I could live in the back of this office. I'll put my futon under the desk and shower at Pineapple Fitness."

I'd sell coffee and tea at the club—this was pre-liquor license—and put on performances. There was no plan. The band Swamp Thing owed me money from being their manager, so I inherited their sound system, which became the PA for the first Knitting Factory.

Luckily, after about two months of being open, we got broken into, and someone stole our sound system. I held a fundraiser and got support from the New York Times, John Zorn, and John Lurie. We held it at the neighboring Puck Building and ended up with a much better sound system. It just grew from there.

Lawrence: I've never heard anybody be thankful for a break-in! What was the genesis of the Music Of series?

Michael: It was born out of the demise of the recording business. In 1999, Larry Rosen, who ran GRP Records, invited me to join Music for Youth, a subsidiary of the UJA Federation. It was a consortium of music industry leaders—BMI, ASCAP, Sony, Universal—raising millions at annual luncheons, with half the money going to music education.

I joined a group of about 30–40 music industry people allocating funds to organizations like Save The Music and Mr. Holland's Opus. But then Napster and technology killed the recording business.

By 2003, the funds dried up. We had a meeting: "We have no money coming in from the labels. How do we raise money?" Being the youngest person at this big table in Midtown, I sheepishly raised my hand and said, "Why don't we put on a show?"

Lawrence: Who is this guy? Who let him in here? (laughter)

Michael: I said, "Why don't we do a show at Carnegie Hall?" They responded, "Are you out of your mind?" I said, "I've wanted to do a Joni Mitchell tribute, and I think Carnegie Hall is perfect." They said, "Too risky. You're a fool."

I said, "I'll cover any losses and give this organization a hundred percent of the upside. There's no risk. Just support it—buy some tickets, maybe bring an artist from your label." They said, "You're crazy. Go ahead." Of course, we sold out and raised $100,000.

By year three, I had become independent and started giving the money directly to the organizations. Twenty years later, we've given over $2 million to music education programs for underserved youth.

I've stayed focused on music education because when budget cuts happen, the arts are the first things to go from schools. Most beneficiary programs provide music education that supplements school programs in underserved communities.

Lawrence: It's cool to see such a diverse portfolio of organizations. How do you think about who to bring into the tent?

Michael: Of the 11 or 12 organizations now, most have been five to eight-year veterans. I'm not actively seeking new organizations. Some years, I might give more to one organization—like when Little Kids Rock showed me their incredible work, I gave them $25,000 each year for four years instead of the usual $10,000.

The common thread is that they all focus on underserved kids and communities. It's like a mutual fund of music-related charities.

An Artistic Celebration

Lawrence: What made Patti Smith the choice this year?

Michael: Patti has performed at five or six of our tributes. She's a New York icon who's very generous with her time. She has connections to Springsteen, The Stones, The Who, R.E.M. She performed on all those tributes and has these relationships, intertwining their lives.

I've been trying to get her to agree for years—I wouldn't say begging, more like bothering her. It's similar to how I've tried with Elvis Costello, but he's told me, "I'm not dead yet." I'll get Elvis someday.

Lawrence: You got David Byrne, you'll get Elvis. (laughter)

Michael: With all of these, I want permission from the honoree. Dolly Parton turned me down. Stevie Wonder's group said, "We got other plans." I respect that. This is more than a cover evening. We want the honorees to know how much the community of musicians loves them and their work.

Patti eventually succumbed to my...

Lawrence: Your wily charms? (laughter)

Michael: More like my nagging emails. The timing worked out well. She gave me a couple of marching orders. When I made my first poster mock-up, she said, "I got a great photographer, Lynn Goldsmith. She's got a book coming out."

Patti's been more involved than most honorees. I'm a little nervous because I want her to be pleased with the show. I'm trying to figure out who's best to read some Arthur Rimbaud. I want it to be an artistic celebration because that's who Patti is. I want to make it more than just a song cycle.

Lawrence: Could you talk about how you assemble the lineup and the house band?

Michael: In our initial call, Patti said, "I want you to work with Tony on the show. I'd like him to be the musical director." That’s Tony Shanahan, who's been a long-time member of her band. Tony gets credit for connecting us with Flea and Benmont Tench from Tom Petty's band. Steve Jordan has been a musical director for several of our shows, and he got the call to fill in for the Rolling Stones. And Charlie Sexton, too. The band is over the top.

There will be a couple of surprises joining the band, and then there were some obvious choices for the lineup. Of course we had to call Michael Stipe. I almost couldn't do this without him. His deep relationship with Patti—we almost had to get permission from him before going to Patti. (laughter)

Shlomo Lipetz, my programmer at City Winery, deserves credit for the rest of the lineup—for every confirmation, you must send 30-40 requests. A thousand musicians want to play, but not everyone's available. Getting the jigsaw puzzle right is partly about availability. But so many artists want to participate that the bill comes together nicely.

Lawrence: So, night of the show, which type of impresario are you? Are you the Bill Graham who's still running around pulling your hair out and tormenting people the night of the show, or do you get to be a fan sitting in the audience while Shlomo worries? (laughter) What's the night like?

Michael: I don't know what kind of promoter I am. I'm certainly more on the anal side than the sit-back type. I've never sat in the audience for the show. For a couple of our shows at Town Hall, occasionally for Steve Earle, all I have to do is start the show with an announcement, which is just bringing Steve up, and it's his show. Usually, I still like to stand on the side of the stage, but a couple of times, I've forced myself to go into the audience and try to enjoy it.

Like anything, if you're a filmmaker, it's not the easiest thing to sit in your screening and watch. I get agitated. Even at other shows I haven’t produced, I naturally need to go to the side of the stage and tell somebody something. It's funny. I'll walk into a building anywhere, and I'm checking out the exit signs, the lights, and the path of egress, like a building department supervisor. That's how I'm built. So in a theater, I'm more relaxed on the side of the stage than in a seat. There's no real need for me to be there. I've got everything coordinated. I'm more of a distraction.

Even at City Winery, I don't need to be there. Don't make me make drinks, and don't put me in the kitchen. I like to cook, but I’m letting people in for free if I’m behind the box office. I’m giving it away for free if I’m behind the bar. I'm more of a negative influence on site.

There is one job I've given myself side of stage: Year one, Joni Mitchell was going to show up. I always intended that the honoree would come. The day before, Joni literally couldn't make it. She was out West, and her cat had gotten very ill. At 6 p.m., two hours before showtime, she sent 50 yellow roses. Each rose had a note saying, "Thanks, Joni." The person at the florist’s wrote the note, but she sent them for me to give to each artist.

So every year, I get 50 yellow roses and hand them out to each artist as they come off the stage. It's become a tradition. That's my only job, but I get to stand next to Springsteen, who watched the whole show from the side of the stage, Graham Nash. These are moments where I feel connected, even though I don't have an important role to play.

Something Chemical

Lawrence: Can you share a story from the City Winery rehearsal shows? They've become such a storied, fabled thing.

Michael: They really are rehearsals. I usually introduce it by saying, "Thank you all for coming. This truly is a rehearsal. We may start a song and then stop. We're going to try to go in the order of the set. Not every artist on the show tomorrow at Carnegie, the second-best venue in New York, is here. Someone from the band will probably sing the song if they’re not. We'll try to do it in order, but since it's a rehearsal, there will probably be some screw-ups. If you don't mind, we'll be starting songs over, and you're here to participate in the process of what we're doing for tomorrow night."

And that is what it is. The night of the actual show is wonderful, but at the rehearsal, they're sound-checking all day. Then they stay for dinner, maybe go to a hotel and come back. But there's all kinds of incredible interaction backstage, talking. You start seeing some artists talking to another artist and saying, "Hey, why don't you sit in with the band for this?" Suddenly, new configurations happen during the rehearsal that weren't part of the plan the day before, and we'll see if it happens the next night. You see some interesting new interactions taking place.

Part of it is also the interpretation of these songs now being expressed by somebody in their voice—who you love anyway with their material—but how they interpret the honoree's work always shines some new light on the song's intention. That part gives me goosebumps. Because when you hear a song that you've been very familiar with done by a new artist, not just trying to replicate it, but giving it some nuance that maybe you didn't see but they did, it takes it to another level.

The rehearsal is where they're premiering it for the first time in front of an audience. During the day, it's just fellow musicians during the true rehearsal. But the rehearsal show is where they can gauge reaction. The beauty of City Winery or any small venue—big plug for small venues—is when you're 15 feet away from the audience and can give back the energy; it feeds upon itself.

There's no better way to understand how well you're doing or how you should spin it, whether vocal or instrumental, than seeing the live effect of your interpretation. There's something chemical there, too.

Lawrence: It's interesting that you mention that energy. When people question why musicians in their 70s and 80s still tour, they don't realize that energy is nurturing and powerful.

Michael: I remember seeing Dave Brubeck at the Blue Note when he was 90-something. They wheelchaired him to the stage, and I thought, "He can't possibly perform." Then his fingers started moving; he began playing beautifully, and twenty years of youth entered his soul. I've seen that so many times. Letting them do what they can for as long as they can is the way to go.

Lawrence: My analog is McCoy Tyner. Those last few years, I'd see him barely make it to the bench, think "This will be rough," and then that left hand would fire up, and suddenly he was there. He needed that energy.

Michael: Yeah, exactly.

Lawrence: you mentioned offering coffee and tea at the Knit early on. Has your approach to presenting live music changed?

Michael: It sounds crass, but we can’t pay the bills without selling food and drinks. The old axiom is "the profits are in the popcorn." Most of the box office—75-80 percent—goes directly to the artist. That 20 percent margin covers production and marketing. We only make money when patrons buy food and drinks.

That said, I wrote a book called Indulge Your Senses. My thesis is that a venue should indulge all the sensory components for everyone in the room. We pay attention to materials, food quality, sound systems, and sightlines. City Winery is a medium between the artist and the audience.

This approach is an antidote to our digital lives. When living on screens, indulging these sensory components makes the experience precious and impossible to duplicate digitally. AI can handle language, sound, and visual art but hasn't figured out smell, taste, and feel. Thank goodness, because I don't want AI replicating live music experiences.

Lawrence: Do you have dream artists for future Music Of tributes?

Michael: I've got a list: Steely Dan, the Grateful Dead, Carole King, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Beach Boys, Jay-Z, Beastie Boys, Fleetwood Mac, Eagles, Tom Waits, and Creedence. By the time I get through these, Radiohead will be ready for theirs. I want the honorees to be alive if possible. I couldn't pay to have more fun doing this.

Lawrence: The Beastie Boys would be fascinating. Hip-hop in general would be interesting to see given this treatment, and they're a great band because they're so versatile musically.

I want to say I'd love to see a Sonny Sharrock show, maybe an Ask the Ages performance with other music around it. I could imagine Nels Cline or Mary Halvorson. There are so many great guitarists now that straddle avant-garde and rock that I think that would be a great night.

Michael: Sonny was one of the most lovely souls I've ever had a chance to encounter. Just a beautiful man. I did a radio show around his work with a bunch of digital audio tapes I found of shows with Mitch Goldman on WKCR a couple of years ago. We must have done a hundred concerts at the Knitting Factory, and he was always smiling.

Believe me, I've had complaints about me from musicians, many deservedly so. Sonny never had anything negative to say. He was just a beautiful soul.

I did a six-artist tour around Europe under the Knitting Factory banner. I had this concept of an egalitarian pay system—I think this came from Marc Ribot—where I paid every musician the same amount. I think it was like a thousand dollars a week per musician. If it was a trio, they got three grand. If it was a quintet, they got five grand. It was this cooperative concept where everything that came in was doled out equally.

Four weeks into the tour, I'm struggling financially—these things are not easy. At the end of the tour, Sonny wanted to have a coffee with me. We were in Barcelona, and he said, "So, Michael, did you learn anything on this tour?" I'm like, "Oh my God, so much. I need to make sure that the venue gets all the backline confirmed a day before." He says, "Well, how about on the pay thing? When the articles came out in the local press, El País for the Barcelona show, what was the headline? What photo did they use almost every time?"

I said, "Oh, it was you, Sonny." He goes, "So you had this system where I got a thousand, and a drummer for this one trio no one's ever really heard of—really good, I love them—but do you think in the end that this was the fairest concept for paying an artist?" I said, "Well, not really. You were the draw for most of it."

Sonny said, "Well, I just want you to think about that." No other artist would ever have that conversation with me like that. Maybe John Zorn—he was very egalitarian and super fair. When Naked City first performed, there were five members, including him. He divided the door into four parts. He didn't take any. He was the only bandleader who ever did that. His idea was, "These guys are doing my music. It'll eventually come to me. But these guys are working." What a beautiful soul.

But Sonny, he could have said something before the tour. It was the last day, and he didn't want anything. He just wanted me to think about it. What a beautiful man he was.

Visit Michael Dorf at michaeldorf.com. Learn more about People Have the Power: A Celebration of Patti Smith, happening March 26 at Carnegie Hall, at musicof.org.

Check out more like this:

Comments