Several years ago, my better half and I were hunting for vegetarian food just outside New Orleans' French Quarter. We happened upon an inviting-looking West African restaurant whose menu more than fit the bill. Food was ordered, and we sat back as a musician set up on a small stage in the front. He was dominated by an instrument I had heard before but never seen in person: the kora.

Several centuries old, the kora originated in modern-day Mali and Guinea. It resembles a huge gourd at the bottom with a long neck extending about three feet upward. The kora has a shape somewhat reminiscent of a harp due to a crossbar at the top of the neck. There's an array of 21 strings, played by both hands, which resonate in the gourd-like chamber. Traditionally, kora players are 'griots,' or storytellers, and the long history of West Africa is intertwined with the instrument. In 2008, UNESCO declared the kora part of an intangible cultural heritage.

The musician at the restaurant played the kora with a difference. Possibly inspired by Frippertronics, he modulated his kora through effect boxes that emulated tape delays. Layers of intricate kora melodies drifted through the restaurant and entranced the several diners. Repeated patterns, echoed percussion against the base, cosmic manipulations—the food was fantastic, but this was even better.

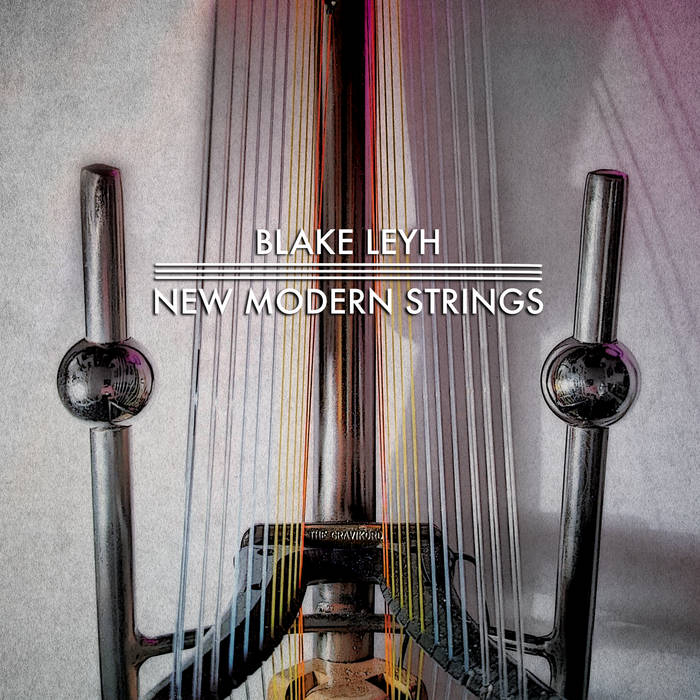

Enter the Gravikord. Invented in 1986 by Robert Grawi, the Gravikord is an electrified approximation of the kora, described as a stainless steel electric harp. It has a space-age look, almost like something Spock might play, and its 24 strings are usually multi-colored. Effects pedals are encouraged.

Blake Leyh, an accomplished musician, music supervisor, and composer for film and TV—he wrote and performed the end credits song for The Wire, among many other things—saw a Gravikord on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Leyh states: "This Gravikord thing immediately inhabited a space somewhere between guitar and kalimba, sculpture and tool, folk and tech, maybe even past and future." Over the course of a day, Leyh went from intrigued to obsessed, tracking down Robert Grawi and acquiring a Gravikord of his own. The album New Modern Strings was soon the result.

Described by Leyh as "a late-style modern collection of music born in the imagined domain of the Gravikord," New Modern Strings features tracks composed on the Gravikord as well as a couple of choice cover songs—Yaz's "Nobody's Diary" and the theme to "The Third Man"—adapted for the instrument. Like the instrument itself, the album ends up pleasantly sounding lost in time. The strings lend an air of the ancient, while Leyh's multitracked instrumentation, including fretless bass, guitar, and electric violin, push the songs into the present. The recording technique, as is the production, is also modernistic, featuring splashes of echo, synthesis, and granular processing in restrained portions. There's nothing flashy here that screams "Gravikord!" Rather, the instrument's novelty, constraint, and beauty fostered an inspiring and joyful sense of discovery in Leyh's process. That comes through when listening to New Modern Strings.

I recently spoke with Leyh about his impressions of the Gravikord, the quick process of composing and recording New Modern Strings, the enduring influence of Jon Hassell, the challenge of being an artist in a capitalist system, and how he approached this album differently than his film scoring projects. The conversation begins below, with Leyh and I discussing my encounter with the kora and how stumbling upon unexpected music happens often in New Orleans.

A Factory of Moments

Blake Leyh: David Simon describes New Orleans as a factory of moments because so much of life happens in public—in the street, clubs, and restaurants. I've got good friends there who I've known for years, and we've never spent time at their homes. The music culture is so outdoors and spontaneous that you're almost assured of encountering some life-changing things at random on a given day. I do find New York to be like that as well, to some degree, but not all places are. New Orleans is, in a way, the most rich with spontaneous experiences of all the places I've been.

Michael Donaldson: Well, New Orleans introduced me to the kora in a live setting. I saw it and became instantly fascinated with the instrument. Did you have any experience with the kora before stumbling upon the Gravikord?

Blake: I heard that album, New Ancient Strings [by Toumani Diabaté and Ballaké Sissoko]. I don't remember where—it might have been on KCRW in Los Angeles. The sound of that music grabbed me. I always loved that album in particular. All kora music is beautiful, and the instrument is stunning.

I did a score for a film called Pray the Devil Back to Hell, which is about the women's peace movement in Liberia. It's from around 2012, I think. When I do a film score for an African film, I'm always very conscious of trying not just to be an old white guy imitating African music. There are various ways of getting around that. I brought in a kora player who is a cousin of Toumani Diabaté. It seems every kora player in the world is related to one village in Mali.

The instrument, the sound, and the vibe entranced me. But I always felt that I never wanted to play the kora for these same reasons. I have loved African music since I first started listening to it—probably King Sunny Adé in the '70s. He was the African musician who came and toured in the U.S. when I was of an age to go and hear live music. Then, I read and listened to a lot of West African music, books, and Real World stuff. I was very interested in African music but always felt wary of appropriation.

Michael: You mentioned in your press materials that you would have been uncomfortable just being a kora player on your own.

Blake: Yeah, it's not like I can intellectually explain or defend that. It's more of an aesthetic vibe. I don't want to be one of these old white guys wearing a dashiki and playing African music. There are enough people who already have that covered. So, when I first saw the Gravikord, it was not a traditional African instrument. It was something else; it had a space-age vibe to it. It has an Afrofuturist vibe, which I am comfortable moving into.

I found the guy, Bob Grawi, who made it. I contacted him and said I wanted one, and he agreed to make me one.

Michael: Is that his only instrument, or does he make various instruments?

Blake: He's an instrument maker but has some other instruments. He's an amazing, interesting man. He lives with his partner an hour and a half north of the city. She plays flute, he plays Gravikord, and they do concerts at the local farmer's market. Occasionally, he is asked to come and speak about the Gravikord or demonstrate it. Yeah, I forget what it's called, but there's like an upright stick string, a washtub bass he invented. He's improved on the washtub bass.

Michael: It seems like it wouldn't be too difficult to improve on the washtub bass.

Blake: But it's a resonator, one string and stick. I forget in what sense it's improved.

Michael: Wow, ready for space age—space age skiffle, a new movement. [laughter]

A Dabbler in the Gravikord

Blake: I'm unsure about Bob's musical background, but he plays the Gravikord. He is a virtuoso on the instrument. I'm just a dilettante, a dabbler in the Gravikord, and I use the recording studio to make this Gravikord music. But I can't play the music on the record live alone. We did a concert—a record release gig a few weeks ago with me and two members of my band, N to the Power. Tony Jarvis played, and Yusuke Yamamoto—the three of us played a couple of tracks from the album. Our band is ideally a 10-piece band, but we have smaller configurations and pop-up versions of the band. I wouldn't say I'm confident playing it live. I can get by. I can make music good enough for people to show up.

Michael: Are there notable differences between the Gravikord and the kora?

Blake: It's a different tuning system with a different number of strings. An electric instrument doesn't make much sound, and it's not even enough to practice—just about, maybe. You have to plug it into an amp. It would be comparable to an electric guitar. So it is electric. Once I have it plugged in, you play through an amp so that you can have reverb or some kind of delay. I think Bob always plays his Gravikord with a delay pedal. It's almost like the delay pedal, with some reverb and tone control, which is part of the basic setup. So, in that sense, it is quite different.

Michael: How difficult was it for you to pick it up, and were any instruments you played before a good primer for developing your technique?

Blake: Its tuning is like a G major or E minor in thirds. So, if you just hold and strum the instrument, it makes a pleasant chord. And so you can noodle. It's not a chromatic instrument, so if you've never played piano and poke at it, the things that come out will not be in any given scale, just random notes. If you randomly pluck a Gravikord, it already sounds like music.

I play a lot of instruments, but none of them particularly well. I've been playing the guitar for 50 years, but sometimes I don't play for six months or a year because I don't have a reason to. I noodle on many instruments and can play well enough to record the music I hear and sing. The pattern of my musical career is to noodle and improvise and work things out from the instruments that I can play well enough, translate the ideas into recordings, and then have other people who play better than I do fine-tune it.

The Opposite of Noodling

Michael: Hearing you talk about noodling on instruments brings me to the Fourth World concept. From my experience experimenting in that area and being a noodler, I know it helps produce what I call "Venn diagram music." In other words, productions that feature elements from different types of music, thus creating something unique in the center. Do you think being a noodler is conducive to experimentation in what Jon Hassell called Fourth World music?

Blake: I understand your "Venn diagram music" concept and hear what you're saying. I was asked to write a small piece about Jon Hassell for Chamber Music Quarterly. The editor asked if I had something, and I said I'd write about the first time I heard Jon Hassell's music, which genuinely changed my life.

That was around 1980, hearing Fourth World, Vol. 1: Possible Musics. The other day, I went and read some of the stuff he was talking about, and there's this interview with him by Glenn O'Brien from the May 1981 issue of Interview magazine. He talks about how he developed his idea for his music, which is the opposite of noodling. It's this very intense dedication to technique. It's how he makes his sound. He studied with Pandit Pran Nath and spent years studying the method of Indian singing and thinking about how to adapt that into a trumpet. He came up with a very rigorous and specific style of playing trumpet.

So, I think Jon's idea of Fourth World music and culture and what that means was grounded in this completely different musical practice that is not noodling at all. The concept of taking disparate elements from other places and combining them exists in many different creative contexts.

I saw the new Eno documentary the other day, so I've been thinking about Eno. I would trace my lineage of not being a virtuoso on an instrument more to the Eno side than the Hassell side of the equation. Jon Hassell has a specific musical identity and voice in those early records.

Eno said a long time ago that he's not a musician; he's a dabbler, and he's someone who just experiments. When I was beginning my musical journey, I spent a day with Eno in 1980 in Santa Cruz in the studio. That had quite an effect on me. I used that idea to get out of having to practice.

Michael: Right, I think a lot of people do.

Blake: Yeah, there's a laziness there. "I can just hit some keys and noodle on a thing, and it sounds great."

Michael: It's like Eno saying, "Oh, I don't write lyrics. I just do weird sounds to the track and come up with lyrics later." And I think people use that as an excuse not to write lyrics.

Blake: A lot of what we call ambient music is people just messing around and noodling. When I'm talking about noodling, I am using that as a self-deprecating way of describing my process. I do not mean it to be derogatory, like it's unimportant, or even an inauthentic musical exploration. But I will say that many people are just noodling and messing around with synths and plug-ins. People can do whatever they want, and the process is valuable for those people, but is the music interesting?

Michael: Yeah, I think you're talking about intention. It's almost like an intention behind your art versus no real intention besides just creating. Nothing is wrong with that, but you're crafting something completely different than lasting art.

Blake: With technology, it's very easy now to make music that sounds pretty good. Eno said this recently, too—you can just buy a plug-in or an app and come up with something that sounds musical. The finished product is almost indistinguishable from music made with more intention.

I was in London two years ago and went to an art exhibit. There was music playing in the background. I was with my godson Vincent, and I was listening to the music. I asked, "What do you reckon, Vincent? Is this fake Eno, or is it actual Eno?" We listened to it a bit, and we couldn't tell. It was just pleasant and consonant. Some bell-like sounds, very sparse. I had to go and read the credits, and it was Eno.

At this point in the development of music technology and the musical tools that we all have access to, I think one has to try a little harder to come up with a personal voice, with a story you want to tell, maybe with some intention. Now, the process of playing music is fantastic, and everyone should do it. Everyone should play a musical instrument, not because they're going to make great music that I want to listen to, but because the act of making music is a separate matter.

A Clunky Process

Michael: I often use random elements when I make music. Like Jon Hassell changing everything for you, my big moment was reading Brion Gysin and Burroughs' The Third Mind, discovering the cut-up method, and having a lifelong obsession with figuring out ways to use that in what I create. Even though I perform random musical processes, there is an intention behind them, even more so than when I used to write music and sit and put this chord behind this chord, and here comes the chorus and the bridge. That was much less intentional than what I do when working with random elements, which is interesting to think about.

Blake: It's even easier to fall into something just ersatz or generic when working in standard musical forms. I see it all the time with jazz. You go to a jazz concert, and the musicians aren't even paying attention to what they're doing. They can just do it on autopilot. They might have amazing facilities with their instruments, and it could be music that fulfills a useful function and is even beautiful. Still, it's different than using music and art to take something inside yourself that's authentic and put it out into the world.

Michael: It's interesting that you mentioned jazz. Jazz came to mind when you talked about Jon Hassell being an advocate, at least in his music, for technical proficiency and studying music. My first thought was that this is so one wouldn't have to incorporate, say, Indian rhythms consciously—they're entrenched in the training. Many people say the same about jazz: you get so into it, so proficient, you're no longer thinking about the instrument.

Blake: That's true with any musical form or artistic practice. You start, and it's a clunky process, and you're doing these most basic things. Everyone did—if you learn violin, you're playing "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star," and it sounds terrible for six months. If you take up painting, you have to learn how to use the brush, and the process at the beginning of any artistic endeavor is one where it's all about the process, and the process feels like it's in the way of your expression. If you keep working, those things become second nature, and then you get to the level where you can express yourself.

Michael: It's like any number of abstract painters. People look at abstract art and say, "Anyone could do that." But then you look at the artist's early work and its super realistic portraits or landscapes, showing they had the chops to be an uninteresting but accomplished painter before they moved into experimentation.

Blake: Absolutely. The other thing is that this idea of having discipline, learning, and spending time mastering techniques doesn't fit well with capitalism and how culture is distributed these days. It's like a young person playing Rock Band, a game where you get 75 percent of the experience of being able to play an electric guitar, but you can do it within 10 minutes.

People love it. Like, it's great. You get a lot of that experience, and you don't have any of the pain or the hard work. It is fun. And there's no reason people shouldn't do that. It's just not what I'm interested in—selecting choices from a preexisting palette and tricking yourself into thinking that is personal expression.

Liquid Modernity

Michael: So, let's talk about the New Modern Strings. I read that "Liquid Modernity" documents your first attempt at recording with the Gravikord. How far along was that song after that first session? How did that come about?

Blake: The album's songs begin from different places, but most of my music starts from experimenting. You find something and play a little further. "Liquid Modernity" got pretty far. It's one riff that's played over and over again, with some other things played against it. The basic idea was there once I found that riff.

Michael: Give me a little background on the concept of the title of that song. You mentioned it as a philosophical concept. I'm intrigued because I'm not familiar with it.

Blake: Liquid modernity is this idea from Zygmunt Bauman, a European philosopher. It's the idea that you have modernism, then you have postmodernism, and then you have liquid modernism or modernity. It's an era at the end of historical progression; everything is more fluid.

The album's called New Modern Strings, which is outrageously pretentious or presumptuous to call your record. It was inspired by a record called New Ancient Strings, and I was trying to make music that had some roots in history and culture but also moved away, trying to create a space on the other side. Someone my age has lived through an entire transformation and seen it surpassed. Things are still called modern, but they're not. I went weeks ago to the Museum of Modern Art, and it's filled with what was considered modern 100 years ago and 50 years ago.

I'm interested in those ideas. What does the future look like, and what does it look like when you sever its connection to the past and engage with it in a more personal way?

Michael: This idea of the new, the New Modern Strings, and severing from the past explains the cover of Yaz's "Nobody's Diary."

Blake: Yeah, exactly. Nobody ever played Yaz on kora, to my knowledge. My daughter loved Yaz and was playing that record, and I thought, "What could I do that would just say, 'Okay, this is not an old white guy playing African music?'" In a way, Yaz is my authentic traditional cultural roots: British music from the 1980s.

I sent some early tracks to my friend Mark Dery, who coined "Afrofuturism." He said, "Yeah, it reminds me of Gaelic harp music," then directly compared it to other British folk music. I'd never made that connection somehow.

Michael: The first time I listened to New Modern Strings, I thought of Penguin Cafe Orchestra.

Blake: That's great. They have influenced my work by combining classical instruments with a more rock music approach. They were one of the influences on the band N to The Power.

Move Quickly and Finish Things

Michael: When I first heard the Yaz cover—and I don't know if this was intended or just me interpreting it this way—it sounded kind of awkward at first. For the first quarter, I thought, "This is cool, but I don't know if it's exactly working. It's kind of odd." But then, it all comes together. It's not like an instant gelling, which is fun. The song goes from "I don't know if this is working" to "Oh yeah, this is totally working."

Blake: That's cool. I think a lot of the music I do has an awkwardness that I intentionally leave in because it's another human element that makes it sound more like me. Another thing about this record and this whole Gravikord project is that it's only been one year since I first laid eyes on a Gravikord.

I like to move quickly and finish things. As I get older, I think about what I want to accomplish. I've seen too much creative work languish because people can't let go of it. And so I think there are times for perfection and times to create, put things out, and keep moving.

Michael: How do you let go? Like, how do you know?

Blake: It's different on different work, but this particular Gravikord thing, there was something about it that just flowed. I didn't belabor much at all about it. Maybe I could have made it technically better, but it would have been different. It's a little collection of music I made on a weird instrument. And when I think about the effects of all the different work I do that goes out into the world—what impact will it have once it leaves my hands?—this record is probably not going to have very much effect. So, it makes sense to be true to the idea and to complete this work, let it go. And it's a joyful feeling to finish work and to let it go. That is when you get the response, but you can't get that until you do let it go.

Michael: I'm also taken with the cover of "The Third Man." I find that to be a nice nod to your work in film. I'm curious about the challenges of adapting these cover songs to the Gravikord. I assume the other songs were composed specifically for the Gravikord, at least the first kernels. So, I imagine the covers were more challenging.

Blake: The Gravikord on "The Third Man" is minimal. The melody is played on guitar. "The Third Man" is mostly guitar. The sound of the Gravikord fits with the rest of the music. I did have to retune the Gravikord for those.

Michael: How difficult is that?

Blake: My god, tuning the whole Gravikord—it's a very cumbersome job. When I picked up the instrument from Bob Grawi in upstate New York, I imagined coming home and immediately playing the Gravikord. Bob handed it to me, but there were no strings on it. He hadn't strung it. I was given a set of strings and an instruction manual on how to put them on. It took 10 hours to get the strings on and tune it, and then it needed a few days to settle down. It has 24 strings.

Music for Music's Sake

Michael: When you're writing the songs for this album—maybe even more so producing than writing—are you thinking visually? I'm always curious about this with music-makers who work in film and visual arts. When I produce music, I try to imagine a tangible space, whether a very realistic space or a completely unrealistic space in which the music takes place. It's something that I don't necessarily reveal to anyone else, but I feel that it works to tie the sound together in a way that other people can sense.

Blake: When making instrumental electronic music, one usually creates a space or a landscape and has that in mind while selecting elements and creating this music. To that degree, almost all the music I write is music for music's sake; it's not meant to go with something else. I do have a feeling of a landscape or a space in which it is taking place that's intuitive. If I'm making a piece with five electronic instruments that don't exist in any physical space, I still think, "Oh, the low tones should be here and have this much reverb in this space. And these high things are like ornaments." So yeah, I think visually about the music I'm creating.

But because I often make instrumental music and film scores, I find the adjective "cinematic" to be trite and meaningless when applied to music. Usually, people mean it sounds like an instrumental film score. Most of what I listen to is hip-hop, jazz, reggae, rock music, or music with a predefined space it lives in. My music doesn't, and it's instrumental, so it has to invoke a landscape or something. So, I resist the idea that my instrumental music is cinematic. I'm just like, "What does that mean?"

I support myself in the world by not making my instrumental music and getting people to pay money to listen to it. It's by making film music and sounds for other people's work. And that work usually prescribes a lot of the stuff that I do. So, if it's a Western, you're making cowboy music. There are a lot of rules, and you're making something to fit into someone else's story, landscape, and space. And I love doing that.

One of the hardest questions with creative work is, "What should I make?" In a recording studio, the parameters are endless if I don't have a preconceived idea. You come up with techniques to create limitations. That's what this Gravikord record is, too. It's just, "I will narrow the guide rails down to this tiny path here. I will make a whole record with this instrument that I can't even play well." And so then it frees you from other choices. We often try to devise a technique, approach, or story to tell ourselves or a way to begin when we have a blank canvas.

I've done it in my life by having two strands of work. One is making sounds and music for other people—to help them tell their stories, support their creative work, and help their creative products—and my music exists in different forms. I do the other thing to pay the rent. When doing this work, I'm not thinking about the concerns of capitalism. I didn't think about it when I put out this record, New Modern Strings. If I embark on a project, I must say, "Okay, this is probably not going to make money." Or if it does, it will be such minimal money that it can't be a factor in deciding if I should make this creative work. It's completely separate from that. I'm free just to pursue whatever wacky ideas I feel like pursuing. I don't have to think, "If I did this, would it be more popular?" I never have to think, "What can I do to be popular?" Not to say I don't want the work to engage with people—everyone making music thinks about a listener experiencing the work.

I feel very lucky to be able to pay my bills by doing something creatively satisfying. I also participate in projects that I respect, that are meaningful to me and others, and have a large amount of visibility, like Treme, The Wire, and something like Neptune Frost. I feel very lucky to be able to do that and then also do my creative work, which I feel is still getting better as I get older, and I keep doing it. I feel like my creative work continues to develop and become deeper and improve. So I feel very lucky for all of that.

A Recommendation

Michael: What's something you love that more people should know about?

Blake: The idea of picking one thing to highlight—when I'm asked those kinds of questions, I usually find someone who I feel can use a leg up in visibility. I've done much of that as a music supervisor, shedding light on lesser-known people. But right now, in a completely abstract conversation, what's one thing I love that I would recommend? It's pretty hard, but do you know this trumpet player Susana Santos Silva? She's a Portuguese trumpet player who plays in extremely extended technique. I saw her at the Big Ears Festival with Fred Frith, and the performance blew my mind. It's not very often that I see someone playing music live and go, "Wow. That is incredible. I've never seen or heard anything like that."

Blake Leyh's Xenotone record label has many exciting releases planned, including new albums from N To The Power (out on November 1) and trumpeter Vincent Curson Smith. N To The Power will also play a record release gig at NuBlu in New York City on October 30.

If you enjoyed this article, be sure to check out these:

Comments