• Solo artist also known as a member of Bernice, Queer Songbook Orchestra, and violinist Aline Homzy’s étoile magique

• Also co-leads the JUNO- nominated MYRIAD3, along with pianist Chris Donnelly and drummer Ernesto Cervini

• On faculty at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music, where he teaches bass in the Jazz Studies department

• Website | Bandcamp | Instagram

Peterborough, Ontario-born bassist Daniel Fortin records and performs across musical worlds—experimental jazz, indie rock, and contemporary classical. His new album Cannon emerged during pandemic isolation as bass guitar sketches, then grew into duets and small ensemble pieces recorded in Calgary apartments, Vancouver rain, and Toronto studios.

Time and distance shaped these ten compositions into something between solo performance and group improvisation. The music reflects Fortin's roots in acoustic jazz with MYRIAD3 and his adventures in art-pop with Bernice. Still, it creates its spare, questioning space—one where a saxophone phrase might appear for thirty seconds then vanish, or synthesizers bloom unexpectedly through the strings of an electric bass.

The conversation below took place over email as Dan prepared for the November 8 release of Cannon on Elastic Recordings, the artist-run label he co-founded.

Lawrence Peryer: How did growing up in Peterborough shape you as an artist? Were there limitations or opportunities unique to growing up there that factored into your creative development?

Daniel Fortin: Peterborough was (and is!) a fantastic place to grow up. My family has long been involved in the theatre and music scenes there, so as a kid, I spent a lot of time hanging around Artspace, the Market Hall, the Gordon Best Theatre, and Bluestreak Records (among other spots). There was so much going on, and I was enamored with the work people were doing and the strong sense of community. It was kind of bohemian. I loved it.

I'm also proud to be the product of a strong public school arts and music education—I had great elementary and high school teachers. At the time, Peterborough's high school arts program was located downtown at Peterborough Collegiate, so as students, we always felt connected to that central arts scene.

I owe most of my playing experience to my pianist friend Jonah, who was a couple of years ahead of me at school. He's the person who got me into playing jazz. He found us a lot of playing opportunities in restaurants around town, as well as at a resort up on Stony Lake. I also got a few other opportunities to play with some older musicians, guys who'd played the dance band circuit decades before since there weren't that many bass players in town. I didn't know what I was doing, but trying to learn on the fly was great. I'm not sure those kinds of opportunities would have come my way had I grown up in a bigger city, to be honest. Learning tunes and playing time on the bandstand was a valuable experience. I love Peterborough—I'd live there now, but it's just a bit too far from Toronto for me (though that distance probably helps preserve its special character).

Lawrence: Cannon features quite an array of collaborators. How did you select these artists, and how did their styles influence the final compositions? Are particular collaborators ever specifically composed for, or are the lineup choices made later on?

Daniel: Initially, I was writing music for another solo double bass record. I started recording solo versions of the pieces and then started listening back, trying to picture what each particular song needed. After a while, certain voices started jumping out—"Hey, I can hear [pianist Chris] Donnelly playing this!" In each case, the guest is someone whose playing I love, who I've been listening to and playing with for years. I feel like their sound is in my bones, and once I started picturing them playing the piece, their involvement felt inevitable. So, while I didn't write these songs for these collaborators, their general influence on me became apparent after I'd written them and started picturing them playing with me.

Lawrence: You pointed out that Cannon deviated from your initial concept of another solo double-bass record. What prompted this shift, and what changes were made to your creative process as the concept changed?

Daniel: This is the first time I'd tried to record anything outside a traditional studio setting. With most of the records I've made, studio time is limited—you're in and out in a couple of days, and by the time the session is finished, you have a pretty good idea of what the record will sound like. I started to get some minimal recording chops together during the pandemic—mostly just so that I could demo my stuff—and what I found was that with more flexibility time-wise in the 'studio' (such as it was), I could let the songs marinate, and to give my perspective on the music a chance to evolve. When Michael Davidson and I made our record Clock Radio in 2019, we spent a lot of time experimenting with our friend [recording and mixing engineer] David Hermiston on the post-production aspect (something neglected with acoustic jazz records a lot of the time). That experience, along with the experience of seeing Bernice records get made, showed me what can happen to a record after the actual recording has taken place—that things don't have to be set in stone, that you can change your mind, and experiment.

At some point a few years ago, I was reading about how the technology they use to X-ray paintings has improved, allowing researchers to see under the various layers of paint. Sometimes, that process can reveal earlier versions of the composition, like "Oh hey, he got rid of the dog there…" I loved that there's this evidence of artists changing their minds halfway through a work—not surprising, but for some reason, that revelation stuck with me. I decided to follow my ideas for this project and not stay wedded to any earlier conceptions. I had a final mix of the record that I'd finished myself. Still, I wanted to hear someone else's idea, so I set my whole vision aside and asked my friend [multi-instrumentalist and composer] Joseph Shabason for his take (which I love).

SpringerOpenStijn Legrand

SpringerOpenStijn Legrand

Lawrence: The track "Minty" with [saxophonist] Karen Ng has such an intriguing structure and, from what I understand, marked the turning point in the album's concept. Could you talk a little about that track and what it says about your openness to letting the circumstance and art lead you instead of clinging to your initial vision for the project?

Daniel: "Minty" is my version of a Nirvana song. I was picturing a guitar-driven sound at the beginning. But then it just occurred to me one day—I need to hear Karen play on this tune for half the head in. I'm not sure where the impulse came from or why I wanted her to play so briefly. I like records where you hear fleeting sounds in the background—like the sonic equivalent of something catching the corner of your eye. I can trace that interest to this Deftones song from their album Around The Fur, where you hear a phone ring faintly near the end of the track. I remember hearing that when I was 14 and being obsessed with it: why did they put that in there? "The Latest Tech" features a couple of faint vibraphone swells sampled from Clock Radio—which I can tie to that earlier listening experience.

For Cannon, I invited guests to appear in each song for a brief interlude: they would each appear for 30 seconds and then exit, and the record would return to solo bass. I liked the idea of inserting unpredictable textural changes in each song, but I only stuck with the brief-guest-appearance concept for a little bit before letting it go. "Minty," "Act II," and "Aplomb" all feature these short appearances. I think Michael's contribution—an entire track's worth of synth textures when I was originally expecting some vibraphone accompaniment—made me let each guest do whatever they wanted without prescribing anything.

Lawrence: How does your work with Aline Homzy, Bernice, and Queer Songbook Orchestra inform your solo projects? Are there specific elements you can point to as manifesting on Cannon?

Daniel: In those bands, I see myself as a bit more of a sideman (which is where I'm most comfortable, honestly. It's probably why it takes me so long to finish my records). But those are all very collaborative groups, where the music is shaped by the people involved—that was the case for records like [Homzy's] éclipse and [Bernice's] Eau de Bonjourno. Aline and Robin are open to everyone else's interpretation of the music. In those bands, it isn't like the songs arrive fully formed and then don't change. So, first and foremost, it's the flexibility in terms of process that I've learned from—letting the pieces develop as a result of everyone's involvement, letting everything breathe and grow. But I also think that those groups are all pretty agnostic in genre—it isn't like there's a particular musical slot we're trying to fit into.

Lawrence: The "Eastern Side of the Ural Mountains" track involves collaborating with your brother, Joe. How does family influence your musical outlook? Does the familial bond add anything to the music or the experience for you?

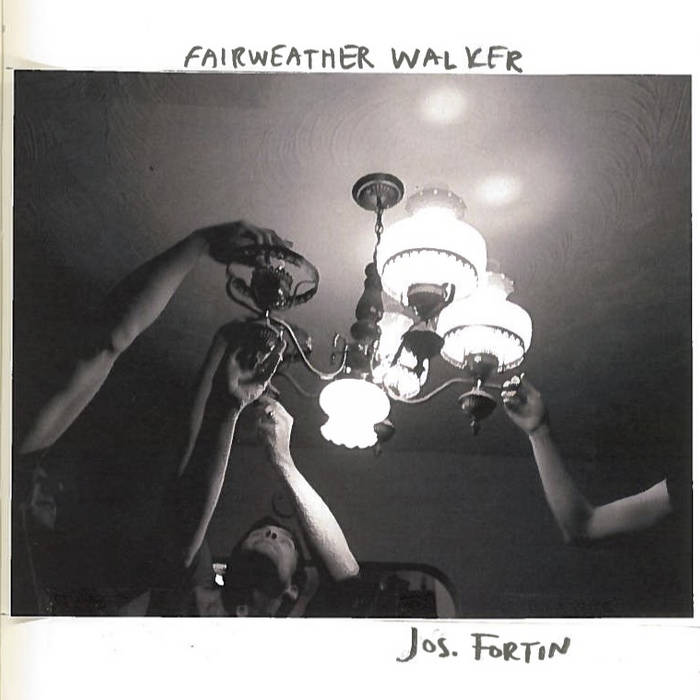

Daniel: That song means a lot to me. It's the only piece on the record that didn't start as a solo bass piece: it began with a piece of Joe's—a slow-burn ambient thing—that I improvised over. It's a part of another project we're working on (more on that later). It's one of the pieces that opened my ears to other textural possibilities on the record. Joe and I have made a bunch of music together over the years (I've had the deep pleasure of playing on his two full-length records), and honestly, there's a certain kind of connection that you only find between siblings. With that piece, this sort of 'I know exactly what you mean!' thing happened the whole time. I recorded the bass part on it when I was first learning how to record, so the sound is a bit hairy, but I didn't see myself being able to recreate the initial performance, so I stuck with the first take. My family is my first and strongest musical influence. There was so much music in the house when I was a kid, and I can still feel the impact of records I heard early on by people like Elvis Costello, Leonard Cohen, and Joni Mitchell. My folks enthusiastically encouraged us to blast our Weird Al and Ren & Stimpy tapes, which was excellent.

Lawrence: How did the multiyear timeline and geographical spread while working on Cannon affect the album? And you?

Daniel: Many of my parts for this record were recorded during the first couple of years of the pandemic. I wasn't working much apart from teaching online, so I spent some time following my partner Zazu around the locations where she worked (she's a film production designer). About half of the bass parts were recorded in a condo in Calgary. These pieces feel very tied to the places where they were recorded in ways that may not be detectable to anyone other than me. "Uh Hundred," "Sparkwood," and "Aplomb" feel like Calgary in the winter of 2021; "Ural Mountains" feels like a deserted East Hamilton that same winter; "Palms" feels like a combo of rainy Vancouver in December and this subdivision in the woods north of Parry Sound in the summer. I think this record took so long for a few reasons, mainly because I'm generally a bit allergic to making plans for my projects, and I didn't know my electric bass recordings would become a record when I first started making them. But also, since I didn't know what the final product would look like, I felt like I had to wait until the thing just felt finished.

Lawrence: How does your approach differ when composing for a consistent group like MYRIAD3 versus the varied lineup on Cannon?

Daniel: With MYRIAD3, we established a pretty strong group sound over the years, and I always imagined the band playing the music while I was writing it. It's a beautiful way to work. Some of the greatest music in jazz history was written for specific people (I'm thinking of Duke Ellington's music in particular—he wrote for specific players). So, I was more used to that process. Writing something with a particular sound in mind (like solo bass) and then abandoning that preconception, which I did with Cannon, was a new way of working for me. It's a process I'd like to pursue further, though I'm currently working on an acoustic quintet record with a few specific players in mind, so it might be a while before I get back to it.

Lawrence: What underlying emotions or ideas were you trying to convey with Cannon?

Daniel: I think of my music as abstract and open to interpretation. I don't try to write music about anything or with a specific mood. I just try to find and stick with an idea to see where it wants to go. I'm honestly pretty turned off by how music is organized in terms of lifestyle and mood playlists these days—I don't like music that tells me how to feel. I want the music to convey mood and emotion, not anything specific. I like leaving it up to the listener.

Lawrence: How do you balance experimentation with accessibility in your music? When, if ever, does the audience ever factor into your thinking during a project?

Daniel: It's funny; getting the right blend of accessibility and experimentation in my music is very important to me, but I don't try to achieve that balance specifically. I just trust that it will happen. Ultimately, I want my music to reflect what I listen to: a balance of experimental and fairly accessible sounds. My favorite music is the kind that takes some work and that rewards close and repeated listening. Sometimes that music is immediately appealing; other times… less so.

Lawrence: Increasingly, it seems your music explores minimalism and space, and on Cannon, even narrative compression. Which artists or experiences, or even other artworks, have influenced this aspect of your work?

Daniel: City life (and life on the internet) feels increasingly noisy and busy, with everything and everyone vying for your attention all the time. Everything feels designed to elicit a strong and immediate reaction.

It's funny (and a bit ironic), but music is one of the best places to find real, intentional silence these days. There are moments of stillness and stasis on this record. I think my listening habits inspire those (I'm thinking particularly of Christian Wallumrød's record Speaksome, which I listened to a ton while I was working on the album in Vancouver). Still, also by a lot of the visual art I've been interested in lately (Agnes Martin and Ellsworth Kelly come to mind). I'm also interested in a lot of art that's a bit more dense and maximalist (films by Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch, the show I Think You Should Leave). I feel like spending time with work that's a bit louder and busier can encourage you to go the other direction in your work.

Also, like many musicians I know, I loved Twin Peaks: The Return. I think about the sweeping scene from episode 7 a lot. There are a few moments on the record where I try to conjure that feeling (whatever it is).

Lawrence: How do you perceive the current state of genre classification in music, particularly in jazz and experimental scenes, where there can be overlap but also wildly different scenes and sounds?

Daniel: I often feel a bit jealous of the metal and dance music scenes, where there's this sort of granular sorting of music styles: all of these micro-genres, where you can accurately describe all kinds of different sounds with an appropriate shorthand. That just hasn't happened with jazz.

At this point, jazz—a term contested from the beginning by pioneers of the music—acts as a massive catch-all umbrella term for all kinds of sounds that don't seem to be immediately connected. It doesn't bother me since I like music that falls under that umbrella. I'm not a purist. But really, music gets handcuffed by notions of genre. There's a real danger when people approach a genre (any genre!) of music with pre-determined ideas about what to expect from it—which is something that jazz and improvised music suffer from. People assume it will sound one way or another and then don't listen. Ideally, everyone would approach every listening experience with an open mind. The other thing I worry about is that by applying 'jazz' to all kinds of music, you end up disconnecting it from its social and political history, which shouldn't happen.

Lawrence: As a faculty member at the University of Toronto, how does teaching inform your musical practice?

Daniel: I started teaching at the Humber College Community Music School right after finishing school, so teaching has always been a part of my work. I don't think of it as a separate job or something I do to support my life as a performer. Everything I think about while onstage I talk about with my students, so teaching and playing is all music to me. Having to explain what you do to younger musicians helps you clarify your own ideas. I think every musician should teach.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments