Throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, The Walt Disney Company offered up a prolific catalog of features using animation, live action, and sometimes live action combined with animation.

The 1990s saw The Walt Disney Company release the first fully computer-animated film with Toy Story (under its distribution deal with then-independent studio, Pixar Animation Studios, creator of the film), and live-action hits such as The Santa Clause, and the 2000s produced classics like The Incredibles and the mega-franchise Pirates of the Caribbean. Since Disney's acquisition of Pixar in 2006, Marvel Studios in 2009 and thenLucasfilm in 2012, in addition to an already thriving roster of original entertainment and a staggeringly successful leap to streaming, it seems like Disney can do no wrong.

Of course, what goes up must come down… And when you’ve been around as long as Disney, there are sure to be high and low points. The mid-1970s through the mid-1980s were a particularly difficult time for Disney, and their creative output shows it.

One aspect of Disney’s output that has almost always garnered praise is the music that accompanies their big-budget hits… or what they expect to be hits, anyway. And sometimes the films themselves were such misfires that the musical score is the best thing that can be said about them.

Let’s take a look at two examples of Disney scores from the late 1970s to early 1980s that outshine the movies they accompany, with some Disney backstory to see how it got to that point, and how it all went wrong later.

Animation Domination

For decades, Walt Disney had been at the forefront of the most exciting developments in animation. In 1928, he added sound to a cartoon for the first time with ‘Steamboat Willie.’ 1929 saw Disney turn this audio innovation into the first of many award-winning ‘Silly Symphonies’ animated shorts, each of which featured an accompanying musical score.

It was his love of music, in fact, that drove Disney’s desire to accompany the scores with his unique visuals, not the other way around. While there was little in the way of recurring characters between early ‘Silly Symphonies’ releases, each one had a lavish score and little to no dialogue. The music was front and center, and his company never forgot what a powerful component of storytelling that could be.

‘Silly Symphonies’ would become Walt’s sandbox, where he could experiment and play with new ideas and techniques that would eventually inform his feature films. He thrived on innovation and was always seeking to take his craft to higher levels of perfection.

Walt struck again in 1932 when he added color to the Silly Symphonies short, ‘Flowers and Trees,’ with brand-new partner Technicolor… which prompted the Academy Awards to create an entirely new category just to recognize the achievement. This earned Walt the first of so many Academy Awards in his career that he still holds the record for the number of Academy Awards won by an individual.

In 1937, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was the first full-length animated feature ever made, was the highest-grossing film in history for a few years, and remains regarded as one of the greatest animated films of all time. In an effort to make the film look as realistic as possible, Disney sent his animators to art school to polish their skills and brought animals and actors into his studio so his animators could get it perfect. Its famously catchy songs made it the first American movie to ever have a soundtrack album released in conjunction with the film and set the standard for all Disney princess movies that followed.

While not every venture was a success upon release (1940’s Fantasia is a fascinating story all on its own), Disney had successfully pivoted his company from being known for animated shorts to extravagant, fully scored feature-length productions, the likes of which had never been seen before.

Through the 1950s and 1960s, The Walt Disney Company continued to release high-quality animated features but was increasingly interested in live-action and hybrid features such as the successful Mary Poppins. The 1960s had Disney releasing twice as many live-action films as in the 1950s, and the company was expanding into television to promote Disneyland.

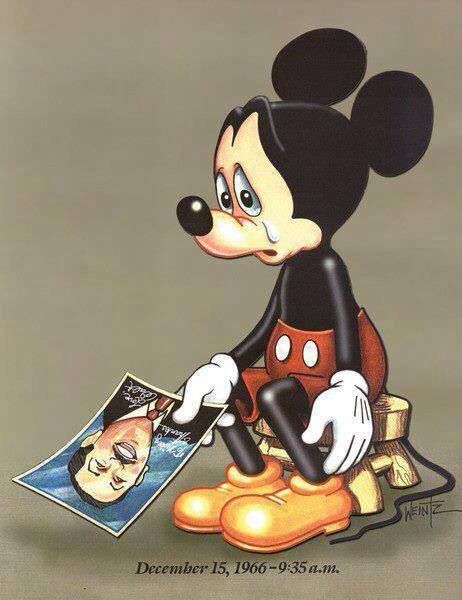

Disney Without Walt

After effectively becoming the name brand of family-friendly entertainment, the death of Walt Disney in 1966 took the air right out of the company’s sails. The Jungle Book was one of the last features Walt personally had his hands in, and it was to be their last big theatrical success for the next 20-odd years.

While their operations were buoyed by theme park revenues, the public seemed to be finding other things to watch… at least in theaters. ‘The Wonderful World of Disney’ pulled solid TV ratings and Disney still scored some noteworthy theatrical hits during this time, but the public simply wasn’t turning out for the big screen experience of titles like 1975’s One of Our Dinosaurs is Missing.

With its visionary founder gone, the company struggled to find its footing in changing times. It wasn’t the idyllic 1950s anymore, and the sheen of the lily-white Disney-fied facade of the United States was starting to tarnish. The artificially rosy optimism of previous decades was being challenged during a time of civil unrest and an unpopular war that upended the patriotic vibe Disney curated. This put Disney executives in the unenviable position of reconsidering their brand without their visionary founder.

A Black Hole of Expectations

When Star Wars debuted in 1977, it became an instant worldwide phenomenon. Disney got out-Disneyed by a whole new take on the classic fairy tale… and make no mistake, Star Wars is a fairy tale, heavily leaning on the concept of “The Hero’s Journey.” Disney had cashed a lot of checks by making films based on fairy tales, but the newest princess in town was named Leia… and she wasn't afraid to use a blaster.

Disney was clamoring to figure out what the public wanted and George Lucas delivered the answer with the resounding BOOM of an exploding Death Star.

For The Walt Disney Company, it sounded like a nail being hammered into a coffin. They had to act fast if they were to have any hope of keeping up.

Their answer? 1979’s The Black Hole.

To be clear, The Black Hole was not a Star Wars ripoff. It’s actual science fiction rather than fantasy… albeit one of the least scientifically accurate movies ever made.

It was first conceived in the early 1970s as yet another of many disaster filmsbeing released by various studios but with the twist of a space-themed setting. It went through many rewrites on its way to being what finally made it up on the screen… for better or worse. It was an ambitious movie. It was Disney’s first PG film, with a violent on-screen murder and a few select “hells” and “damns” sprinkled around for good measure.

Before even a single frame of sci-fi excitement (such as it is) flickers across the screen, “The Black Hole Overture” appears in digital lettering over a black background reminiscent of an old-school digital alarm clock. With it, we’re treated to the first strains of John Barry’s boisterous score.

It was one of the last big movies to make the brave choice of leading with an overture before the opening credits even begin… particularly since, in this case, it makes a bold promise the movie simply can’t live up to.

John Barry was already a popular and successful composer with two Academy Awards to his credit from 1967’s Born Free. With several ‘James Bond’ titles under his belt as well as the 1976 remake of King Kong, Disney needed a composer with the gravitas to compose a dignified, grown-up score to The Black Hole.

It was Barry’s first Disney film. In addition to his 94-piece orchestra, he updated his sound by flirting with synthesizers and the blaster beam, a cacophonous 12-18’ long electro-acoustic aluminum and bronze instrument that produces sounds that may be best described as space garbage colliding.

With George Lucas’s Industrial Light and Magic being unavailable (and prohibitively expensive), Disney looked inward to create several new technologies to bring their special effects to life. Indeed, it was nominated for Academy Awards for Best Visual Effects and Cinematography. Barry’s score was the first to be recorded digitally, so the digital lettering accompanying the ‘Overture’ may have been more than just an aesthetic choice.

Though The Black Hole had its genesis around the same time George Lucas was first writing Star Wars, it ultimately winds up being one of many post-Star Wars and pre-The Empire Strikes Back movies to try to hurriedly elbow its way into profitability. Yet it simply isn’t good enough of a movie to actually compete… and its box office returns verified that.

It has a small cult following that willingly overlooks a clunky script, slow plot, cutesy robots “flying” on visible strings, and an incomprehensible ending that the writers themselves can’t explain… but watching Anthony Perkins get (bloodlessly) eviscerated by a robot baddie and the unforgettable enormous glowing meteor bursting it’s way through the glass hull of a huge spaceship are just the kinds of spectacle you want to remember when listening toBarry’s swirling, imaginative, and captivating score.

Something Flaccid This Way Comes

Horror movies were certainly nothing new in the early 1980s. Still, they weren’t something Disney had even considered adding to their brand aside from characters like the Old Hag in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and the devilChernabog from Fantasia.

After the Academy Award-winning The Exorcist made a fortune in 1973 and the critically acclaimed independent hit Halloween raked in $70 million against a budget of $325,000 in 1978, horror was gaining mainstream respectability (and profitability) in a way that couldn’t be ignored.

Disney’s first real effort to cash in on this phenomenon was The Watcher in the Woods, an obscure horror/sci-fi failure released in 1980. Plagued by studio interference in an attempt to sanitize anything that might be kind of frightening or even a little controversial, its reviews remain mixed but with universal hatred for the ending.

Still determined to strike gold by offering more mature fare, 1983’s Something Wicked This Way Comes suffered many of the same problems.

Based on a screenplay Ray Bradbury wrote based on his 1962 novel of the same name, Something Wicked This Way Comes might have seemed like a smart choice at the time. The lead characters are two 13-year-old boys, and the moral of the story is that love and happiness can defeat darkness and evil. What’s not to love, right? Disney executives probably heard the distant, echoing cha-ching of a cash register.

However, unlike The Black Hole, which was a messy movie but had the full support of the studio, Something Wicked This Way Comes was doomed with a troubled production from beginning to end. The book is a nostalgic, slow, heady dark fantasy perhaps not best suited to appealing to the intended audience of young adults, especially when challenged by the limitations of its budget.

Full of optimism and desperate for a big-screen hit, Disney sought the input of Bradbury himself and hired his director of choice, Jack Clayton. Naturally, the two wanted to stick as close to the novel as possible. French composer Georges Delarue was Clayton’s pick for scoring the film, having collaborated on two previous occasions. Delarue was excited about scoring the film and hoped it would help him make it big in Hollywood.

On the other hand, Disney executives were unhappy almost from the beginning. They still hoped to make a movie with an openly evil proprietor of a sinister traveling carnival who enslaves townspeople with their greatest desires into a 90-minute family-friendly affair. With the production veering away from its sterile vision, the studio stuck its hands in the pot and stirred it in the hope that profits might yet congeal somehow.

Test audiences found the movie horrible (but not in the intended way.) Disney ultimately snatched the film out of Clayton’s hands, spent $5 million (doubling the film’s puny budget) on six months re-shooting and re-editing, chopping out innovative special effects including early computer animation… and, mercurially referring to the score as “too dark,” entirely scrapping Delarue’s work.

James Horner, who was still early in his career but had recently hit big with Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan in 1982, was brought in to write a new score in keeping with the revised version of the film.

Even with all of the changes, test audiences were still less than thrilled with the movie. After its release, Something Wicked This Way Comes flailed, earning even less against its budget than The Watcher in the Woods. It’s a visibly chopped-up, jumbled affair that never really seems to get a hold of its own narrative. One of the worst things a would-be horror movie can be is boring.

When it comes to a score for this film, listeners are spoiled for choice.Horner’s score was released in 1998, while Delarue’s score came much later in 2015. It’s hard to argue against the perfection of Horner’s score for the final release because Delarue scored a much different film. Comparisons between the two are ultimately like comparing apples to oranges, with both scores being darkly beautiful in their own ways.

Three for the Price of Two

It can be hard to imagine that there was ever a period when The Walt Disney Company struggled to crank out the hits. Disney learned from this period and achieved tremendous success when they branched out with Touchstone Pictures in 1984 to distance the Disney name from movies with mature themes. And, while The Black Hole and Something Wicked This Way Comesmay not be great cinema, they’re interesting footnotes in Disney’s storied history. They’ve both been getting kicked around for reboots for years now, but whether or not that happens, we still have three great scores to enjoy between two films that missed their marks.

Comments