Born into Danish musical royalty as the son of classical composer Herman D. Koppel and pianist Vibeke Koppel, it's no surprise that Anders Koppel and his siblings ended up on the piano bench. But a recording of Fats Waller changed everything for young Anders—the organ, specifically the Hammond B-3, would become a lifelong obsession. However, this was hardly a repudiation of his father's symphonic influence. While many aspiring organists of the late 1960s were emulating Jimmy Smith's bluesy swagger, Koppel was captivated by Waller's orchestral approach, hearing the possibility of the organ as a complete symphonic voice.

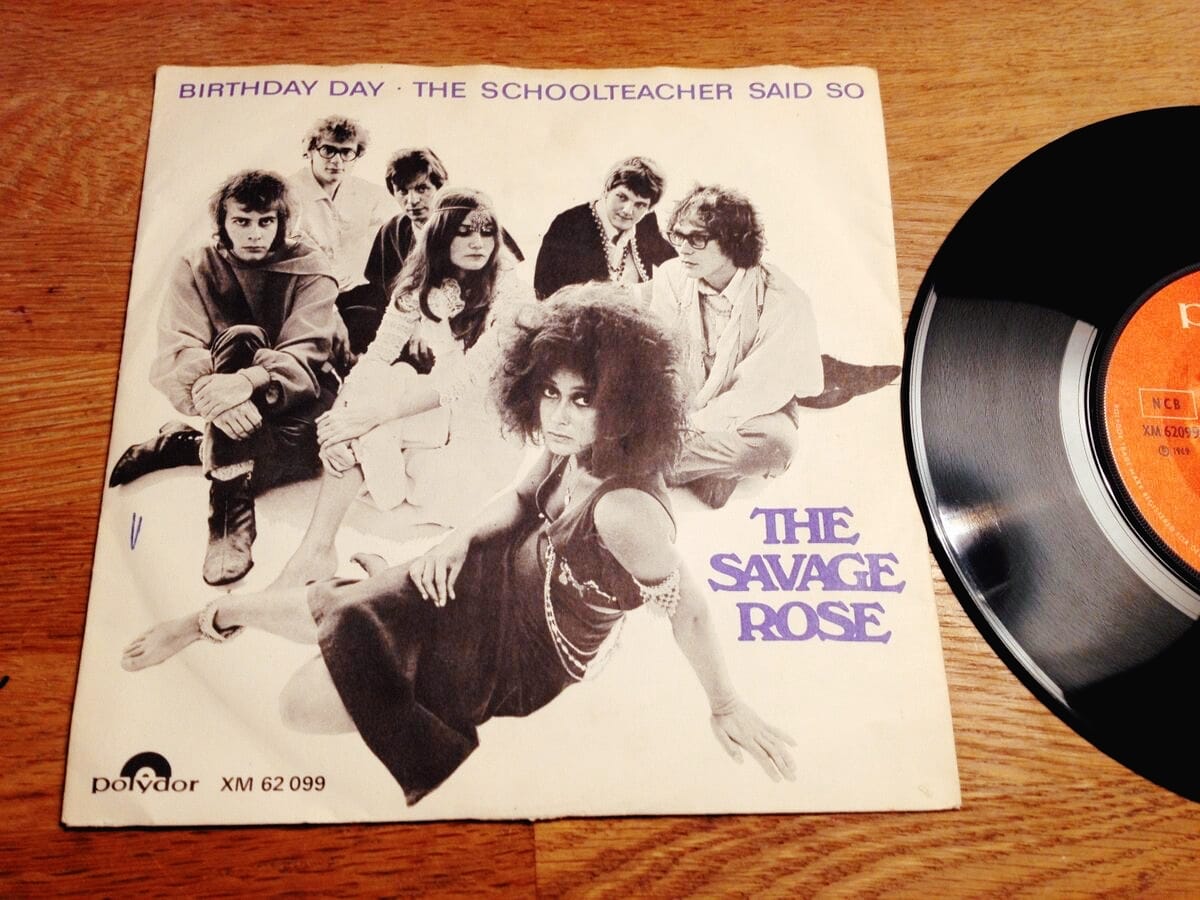

This orchestral sensibility would shape Anders's distinctive style, first with the progressive rock band The Savage Rose (which he co-founded with his brother Thomas and sister Annisette in 1967) and later in his expansive repertoire spanning jazz, classical, and soundtrack music. Now in his seventies, Koppel maintains a vigorous dual career as performer and composer, collaborating frequently with his virtuoso saxophonist son Benjamin on the prolific Cowbell Music imprint. The Koppels' music spins a generational tale.

On the Spotlight On podcast, Lawrence Peryer spoke with Anders Koppel about his long and fascinating career, musical memories from the 1969 Newport Jazz Festival, how his father's work ethic was passed down to his son Benjamin, the intricacies of the Hammond B3 organ, and much more. The interview below has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Heart of the Music

Lawrence Peryer: Over the last few days, I've been immersed in Time Again. It's just such a beautiful album. When I listened closely, I noticed that the trio format lent itself to hearing your pedal work. It's delicate yet prominent and propulsive. I'm curious how you found yourself seated at a Hammond B-3 and what that journey was like.

Anders Koppel: My father had a record collection of 78s from the thirties with Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Fletcher Henderson, and Art Tatum. That was a big influence. I listened to the records over and over again when I was maybe fourteen. As a young man, I got an album of Fats Waller playing the London Palladium Organ as a birthday present. That was a revelation for me because he played the organ not so much as jazz but as symphonic jazz. He played it like a symphony orchestra. Immediately, I knew that's what I wanted. I got a cheap Italian Farfisa organ, and eventually, I got a smaller Hammond. Thomas, my pianist brother, and I started The Savage Rose in 1967. Around 1969, I got the B-3.

We had reduced the group to a trio—me, my brother, and Annisette, the vocalist. Since we had no bass player, I was responsible for the bass. I got the B-3 with the two-octave pedal work and started practicing. I love playing the pedals because the bass may be the heart of the music. It keeps everything together and gives direction.

Of course, I play with bass players from time to time. For instance, I've played several times with Scott Colley, and that's a whole different thing. Maybe it liberates me because I don't have the duty of keeping everything together with the bass. But for me, the instrument is only complete with the bass.

The Fats Waller record probably inspired my way of playing the organ. Of course, I'm a big fan of Jimmy Smith and all these great jazz organ players, but I'm coming at it from a different direction. For me, it's more of a symphonic thing.

Lawrence: How does that contrast with Jimmy Smith or Groove Holmes? What does symphonic imply that's different than those players?

Anders: Maybe it implies more curiosity about the sound because the Hammond organ can be like a flute or a cello—it has many different colors. And Jimmy Smith usually plays with one setting, more or less. I'm especially a big fan of his ballad playing because I think he's much more liberated in sounds. He listens to the sound in a whole different way than with his up-tempo songs. He masters those fantastically, but his ballad playing is exquisite.

Lawrence: The organ tends to cut through. It can hit a certain treble range, or it has a shrillness that is a neat attribute when soloing or comping. Still, there's more of a textural element here in what you're doing, and I think the piece that's falling in for me is that you've played in many smaller ensembles where the organ had to be a glue.

Anders: I played in a trio called Bazaar for thirty-six years. That was the wind player playing bassoon, electrical bassoon, and clarinets, and then percussionists. And, of course, that left me with harmony, with everything.

I've played alongside a percussionist with Benjamin for many years. And every time Brian Blade was in Denmark, we had some gigs. Playing with Brian is a big inspiration because he's a genius, a wonderful musician, and a wonderful man. The thing with Brian is that he is easy to play with because he catches everything you do. But he never stresses about hearing everything. He makes everything natural. He develops music in a very organic way. That suits me well, as it does so many others.

Lawrence: I love watching Brian play—just the physicality and how he moves the music. It's incredible.

Anders: It's pure joy. He loves music so much. We had a fantastic collaboration around the Mulberry Street Symphony, which is a big work—ninety minutes of music for a trio, namely Benjamin on alto sax, Scott Colley on bass, and Brian on drums, and symphony orchestra, which I composed especially for this trio. Brian doesn't usually play with a symphony orchestra, and I didn't write anything for him in that situation. I made a transcript for piano of the orchestra parts, and he followed that, and he filled in as he knew the music inside out. He's very thoughtful.

You know, the day before we recorded Time Again, which was recorded in one day in the studio, my wife and I celebrated our golden anniversary—fifty years of marriage.

Lawrence: Wow.

Anders: We had a big party, and Brian and his wife, Laura, were there; they are part of the family. So when we went into the studio the next day, we felt happy because we had this wonderful celebration inside of us, and the music came alive, and everything was really sweet. Every take on the record is a first take. We didn't do any retakes.

Lawrence: I remember the first time I sat at a B-3 in a recording studio. I thought, "How does one person do this?" It seems like it would take six people between the drawbars, pedals, stacked keyboards, and Leslie control. It's such a potentially complex instrument in terms of combinations of elements. Is there a sense of opportunity for you to learn new things?

Anders: Always. It's no different than the piano. The organ is such a rich instrument, but so is the piano. One would think there are not many possibilities for a piano. But the possibilities are endless. Once you get into the music's sound soulfulness, you don't think about possibilities—you just want it to sing.

I also find that my focus shifts from time to time. I discover new sounds or old ones I haven't been into for years. I think, "Wow, I want to use this again." So, it's a continuous process.

Oil and Develop It

Lawrence: I'm very curious about the musical relationship with your son, Benjamin. It's funny to talk to you now because I spent some time with him, and I'm realizing that there are multiple traits that the two of you share. You both seem to share lightness and humor while being very serious about the music. How did you come into that personality? Was it from having an artistic family or growing up with an artistic parent?

Anders: Yeah, that's a big question. Looking back on my life, I know I got a lot from my father because music was a very serious matter for him. If you devoted yourself to music, there were no shortcuts. You had to go all the way. Also, being a composer is like maintaining machinery. You have to oil and develop it. So, I learned the basis of this from my father and my relationships with the musicians I worked with.

Benjamin is a virtuoso. I mean, he really can play anything. I know he works hard, and I work hard. We made a lot of music together, even when he was six, and we have been playing together ever since. Part of our relationship is to give each other great opportunities. I've written five saxophone concertos for him and concertos for saxophone and symphony orchestra. We give each other opportunities and new ways of expression.

Lawrence: Did you share any artistic life with your father?

Anders: Yes, of course. When I was a child, I played the piano. Later, I played clarinet; I played recorder when I was very small. My father wrote several pieces for me for recorder and piano. Later, he wrote for clarinet and piano, which we played in concerts when I was maybe fourteen or fifteen. We did many things together and had a very strong artistic relationship.

He was always very interested in what I was listening to. For example, when I listened to Jimi Hendrix, my father wanted to know all about him. When I entered a Bob Dylan period, he wondered, "What are you so occupied with?" And he listened to it and The Band and all of that.

Lawrence: What did he think of rock music? Did he find things that resonated for him?

Anders: Like all true musicians, he didn't use the labels. For him, it was all music.

When I was seventeen, my brother and I started The Savage Rose. It was a huge success from the start. It was interesting because it was a rock band, but it was a different kind of rock band because we were influenced by classical music. My father understood that it had different harmonies and a unique way of thinking about music.

Lawrence: Do you still listen to newer music? Or do you have a canon that you revisit repeatedly?

Anders: My time catching up with new trends and music is more limited now than when I was young. I had a lot of time then because I made an album occasionally and was touring. Now, it's more of a question of pursuing my path. So I cannot say I'm very much into the new trends. I hear things, but I'm in no way complete.

Lawrence: It's pretty much impossible to be these days. There's so much music. It's so exciting, but it's so daunting.

Anders: I read that every day, three hundred thousand new songs are being put on Spotify and all of these platforms. Three hundred thousand songs.

Lawrence: I see a lot of hand-wringing about how there's so much music, and not much of it's good. But that strikes me as a net positive for the world. My sort of pithy one-liner about it is that, of all the world's problems, I wouldn't put too much artistic output in the top five.

Anders: Neither would I. But the industry is changing so rapidly that it's hard to keep up. Maybe that's the hand-wringing situation because how do we orient ourselves in a world that is quickly changing? Even concerts are changing.

When I was a young man, we made our albums, and we could go into the studio for a month and make these incredibly developed things, as the Beach Boys or The Beatles did. We made artistic statements in the form of an album. That's impossible because you can't make money from music that way anymore. So everything is changing; maybe I cannot say if it's for the better or the worse. The world has always been changing, but it is changing in a very quick manner now.

I once recorded an album with Kenny Werner and Benjamin titled Everything Is Subject to Change. That statement is truer now than ever.

I Don't Know About Jazz

Lawrence: A hallmark of your career is this integration of genre; you take inspiration from wherever it strikes you. You don't seem limited.

Anders: Your music reflects the music you are into, and I have been into many different types of music. I have been into Cuban, Turkish, jazz, classical, African, and Brazilian music. So, I have focused on a lot of things that are now reflected in my music. And I think Benjamin and I are like each other in this way: we are not limited by what others call labels or genres.

I'm into music. I once saw an interview with Duke Ellington on television, and he was asked a question: "Mr. Ellington, what is jazz to you?" And Ellington says a wonderful Ellington-esque quote, He says, "Yeah, I don't know about jazz, I know about music." And he always maintained that view. It wasn't just a smart remark on a television show. He meant that he didn't care about jazz; he cared about music.

That's so wonderfully reflected in his music; he is open to inspiration. Open to sound, open to new ways of doing things. Inspiration from everything. I think Mr. Ellington was right, and I feel the same way.

Lawrence: Did you ever see him perform?

Anders: Yes, I did in the Tivoli Concert Hall. He was very sharp-looking, and of course, it was wonderful. Johnny Hodges was there. I also saw him in 1969 when my band, The Savage Rose, played at the Newport Jazz Festival. He was there with his band, and I heard it. He's always been one of the stars in the sky.

Lawrence: Who else do you remember from that '69 lineup?

Anders: That was the year when the Newport Jazz Festival opened up to other genres. So there was rock music and soul music, James Brown. My band was scheduled to play after Sly and the Family Stone.

Lawrence: Wow.

Anders: It made me a little nervous because they always were and still are one of my favorite bands. I love them very much. It's such original, fantastic music. They tore the place apart; everything was in riots after the show. And so luckily our performance was postponed to the next day.

Lawrence: Give everybody a chance to cool down a little bit. [laughter]

Anders: But I heard so many things there. James Brown, as I mentioned—everybody was there. It was fantastic.

Lawrence: That's an interesting era when the concert bills mixed genres. Here in America, you had Bill Graham putting Miles Davis opening for the Grateful Dead or the Jefferson Airplane, or some of those rock bands would go to Europe and play on jazz festival lineups. It's such an interesting time to illustrate that comment from the musician's point of view; it makes sense to be in all those contexts and environments because they're all just playing music.

Anders: And Sly and the Family Stone inspired Miles. So everything is mixed anyhow. Let's just keep it that way.

Make Their Instruments Sing

Lawrence: You have some interesting projects coming up. I'm wondering about your interest in composing for military brass bands.

Anders: I love the sound and the homogeneity of the sound of the brass instruments. So, in the autumn, I wrote a piece based on seven poems written by children in Theresienstadt Concentration Camp during World War II. It was a huge success, and now it will be played in the museum in Theresienstadt in Prague, Czech Republic.

Writing for such ensembles as a military brass band or a string quartet is inspirational. It's very easy to write good-sounding music for them. I love writing that music.

Lawrence: Yeah, there's something beautifully subversive and very pointed from a commentary point of view about juxtaposing the children from the concentration camp with the sort of military martial style of music. It's very powerful.

Anders: The military or brass band can be much more than marching music. It's any music you write for them; you can write anything. You don't have to write marches. I write soulful tunes for these instruments. In Denmark, and I know in America too, the musicians in the military bands are very skilled and very good. So they can make their instruments sing like any other orchestra.

Lawrence: What's the cadence of your creative life at this point? Is part of your year composing and part of your year performing?

Anders: When I'm not playing, I'm composing. When I'm not composing, I'm playing. Maybe I'm playing a little less than I used to when I was younger, but that's not my choice. I think it's as much a question about the markets and how live music is changing.

But I'm still playing. I have different bands. I play with Benjamin, and I have a trio. I also have a duo with a cello player, and we play together every month. I also play from time to time with my daughter Marie, a soul and gospel singer. So, I'm busy as a musician and a composer. And I hope to keep it that way.

Learn more about Anders Koppel at wisemusicclassical.com. Purchase Time Again on Qobuz or Bandcamp, and listen on your streaming platform of choice.

If you enjoyed this, be sure to check these out:

Comments