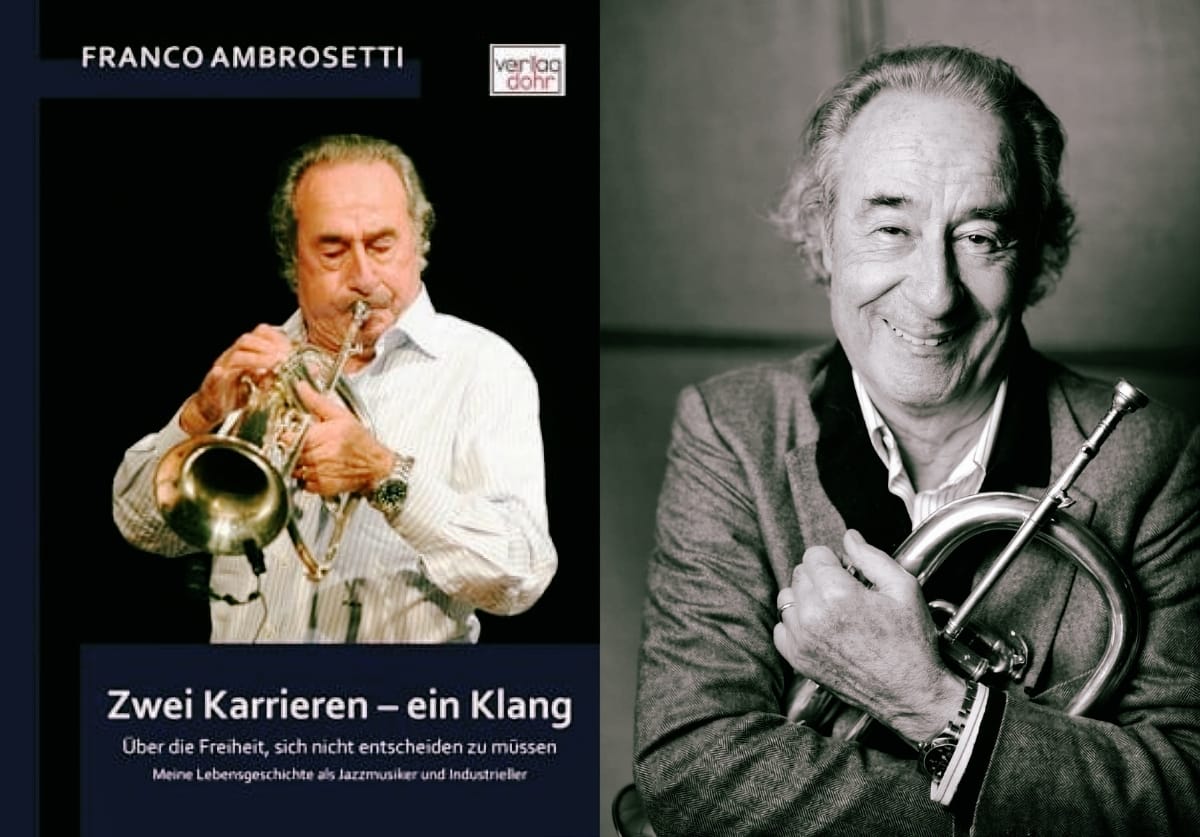

European jazz trumpeter Franco Ambrosetti embodies a rare duality in the modern music landscape—a successful business executive who maintained a thriving career as a respected jazz musician. Born into a musical family in Lugano, Switzerland, Ambrosetti followed his father's footsteps in business and bebop, eventually leading the family's industrial manufacturing company while performing alongside jazz legends like Dexter Gordon, Phil Woods, and Michael Brecker. His ability to balance these two worlds led him to pen his memoir Two Roads, Both Taken, challenging the notion that one must choose between artistic passion and business acumen.

After selling his business in 2000, Ambrosetti focused primarily on music and continued exploring his creative impulses. His story is a template and inspiration for pursuing multiple passions without compromising.

Through candid observations about musical evolution, the development of "soul" in performance, and the cultural contrasts between European and American attitudes toward musicians with multiple careers, Franco offers unique insights into both the business and creative worlds he navigated for decades.

Lawrence Peryer: What early musical encounters shaped your direction as a musician?

Franco Ambrosetti: All the musicians that were in the group with my father were influential: George Gruntz, with whom I played in Duo, Trio, and Big Band (George Gruntz Concert Jazz Band); Daniel Humair with whom I still play; and, of course, the musicians who visited us, Benny Golson, Nat and Cannonball Adderley, Romano Mussolini with whom I did my first tour in 1961 and also the first concert of my life in Rome. There’s also Barney Wilen, Woody Shaw, who was coming to Zürich when I was at the university, Raymond Court (who was a member of my father's quintet before me), Kenny Clarke, later Friedrich Gulda, Freddy Hubbard, etc.

Lawrence Peryer: How did watching your father balance music and business influence your choices?

Franco Ambrosetti: I understood that my father's ambition was that I would follow his steps into the family business. So, I did, although my ambition was to go to the US and be a professional musician. But now, and even then, I didn't regret following my father.

Lawrence Peryer: How has your approach to interpreting ballads evolved since your father's early critique about playing them "correctly but without soul"?

Franco Ambrosetti: The "soul" came with the age. "Soul" comes after one has experienced frustration (like when a girlfriend lets you down). Soul means, I think, expressing your deepest feelings, the wounds you collected—especially in love affairs—and the failure you've collected. It comes and never goes away.

Lawrence Peryer: Your book’s title, Two Roads, Both Taken, challenges the famous Frost poem's premise. What made pursuing parallel careers possible?

Franco Ambrosetti: I've learned that one can practice two jobs and be successful in both, like managing a company and playing music, if one has a tolerant boss. My father was a musician and businessman—my best example!

Lawrence Peryer: Most trumpet players take frequent breaks to rest their lips during practice. You developed a different approach: playing for 30-45 minutes without removing the mouthpiece. What led to this unusual method?

Franco Ambrosetti: It's about the time. I had little time to practice after 8-9 hours at the office and maintaining a family with two kids. I had to invent something to keep my "chops" in good shape.

Lawrence Peryer: What insights about leadership and collaboration have you found true in corporate boardrooms and jazz clubs?

Franco Ambrosetti: Leadership and collaboration are important in both fields. Leading a big band is not so different than leading a small company manufacturing wheels.

Lawrence Peryer: How do you manage the psychological balance between your business and musical lives?

Franco Ambrosetti: During a jazz tour, you feel the pressure of performing, traveling, etc. Therefore, it's nice to return to your elegant office and deal with totally different problems. When business problems hang overhead, it’s like a vacation to go on a jazz tour and breathe fresh air.

Lawrence Peryer: How does risk-taking differ between your business and musical ventures?

Franco Ambrosetti: In musical improvisation, the risk is immediate: you might hit a wrong note during a solo. In business, realizing that you made a mistake may take a long time. And, in music, it concerns you alone; in the business, it may involve many people. Mastering the mistakes is important in both fields.

Lawrence Peryer: Italo Calvino wrote about "lightness" in art—removing weight and density to find elegance. You've discussed this in relation to music. How has your playing evolved?

Franco Ambrosetti: I played too many notes and song phrases when I was young. Then I heard Miles Davis and his evolution from too many notes when he was with Charlie Parker to fewer and fewer notes as he grew older. "Only the best notes,” he said. No need to be prolix!

Lawrence Peryer: What's your perspective on jazz education and its standardization?

Franco Ambrosetti: The gain is that more people know about jazz. The loss is a standardization of jazz improvisation: between Ornette Coleman and Stan Getz, there is a big difference. You can teach what are the right notes to improvise the blues, but not the style one should choose.

Lawrence Peryer: In the 1960s, many Communist states viewed Western jazz suspiciously, yet audiences embraced it. What did you observe about jazz's role when performing behind the Iron Curtain?

Franco Ambrosetti: I realized the only way to escape "tyranny" is jazz improvisation, which means "liberty.” At last, the freedom to improvise! Jazz is freedom!!

Lawrence Peryer: American jazz clubs often celebrated musicians with diverse careers, like doctors and lawyers who played professionally. You found a different attitude in Europe. Could you explain this cultural contrast?

Franco Ambrosetti: In the south of Europe, the moralistic aspect is dominant; therefore, being talented in more than one profession is suspicious. There is a basic conviction that one can excel in only one job. Not two! Especially when you are well-off.

Lawrence Peryer: Coming from Italian-speaking Switzerland, you've described the culture shock of working in Zürich's banking world while playing jazz. How did that experience affect you?

Franco Ambrosetti: The austere culture is a legacy of Protestantism (Zwingli in Zürich, Calvin in Geneva). But freedom was generally present in jazz clubs. Improvisation without freedom is unthinkable. In my later life, it is still the same.

Lawrence Peryer: What made your musical connection with pianist Geri Allen special?

Franco Ambrosetti: Geri Allen was a fantastic person and a great, highly-gifted pianist: the feminine version of Hancock's finesse.

Lawrence Peryer: How did your Bach project with Uri Caine develop?

Franco Ambrosetti: Bach was a great improviser. He took a theme in the Goldberg Variations and created many versions of it. Since jazz improvisation follows similar rules—keeping the original chord sequence while creating new melodic lines—it was natural for Uri and me to approach Bach's music this way, respecting his spirit of innovation.

Lawrence Peryer: What inspired the selection of musicians for your recent album Cheers?

Franco Ambrosetti: I simply invited my dear friends to a "musician's party.” I'm not very happy with the album; I was not in good form. I'm not satisfied with the results.

Lawrence Peryer: What trends do you see affecting jazz's future?

Franco Ambrosetti: I think that jazz follows what happens in classical music: in the classical world, they still play Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, etc. The same will happen to jazz. But jazz was the trigger that brought back the improvisation that Bach and Beethoven were using. Nowadays, even the cadenza is starting to be improvised.

Lawrence Peryer: Which emerging musicians give you optimism about jazz's evolution?

Franco Ambrosetti: None. After the "free jazz" and "fusion,” nothing really happened. But I hope improvisation will not disappear.

Lawrence Peryer: What creative directions are you currently exploring?

Franco Ambrosetti: My next recording will be with a five-member singing group, arranged by Alan Broadbent. We’re recording in New York City this October.

Stay updated on Franco Ambrosetti at francoambrosetti.com and follow him on YouTube and Bandcamp.

More modern trumpet masters:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Spotlight OnSpotlight On

Spotlight OnSpotlight On

Comments