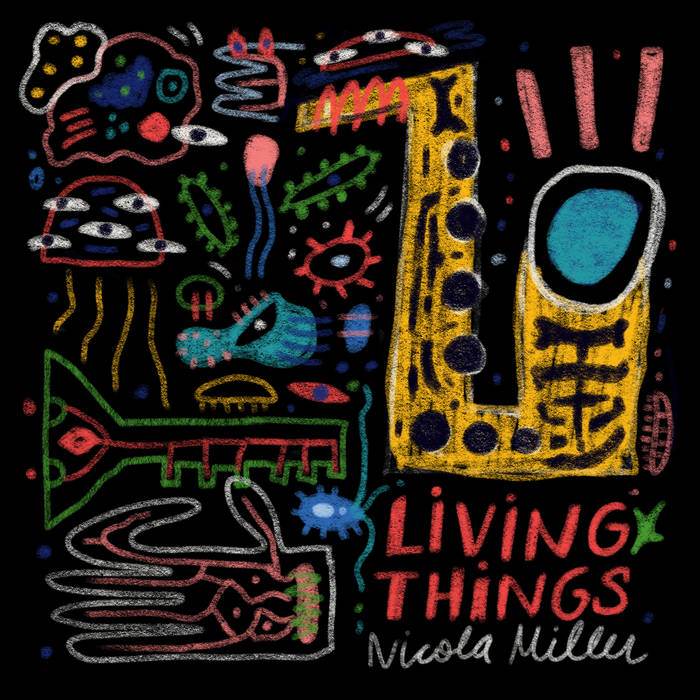

Two hours north of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, composer and saxophonist Nicola Miller has built a creative life where solitude feeds her work. Her debut album, Living Things, on Cacophonous Revival Recordings, grows from close observation of maritime nature—bufflehead ducks gliding on water, wind-bent poplars—shaping these moments into music that moves freely between jazz, experimental forms, and chamber composition.

After finishing her jazz studies in the early 2000s, Miller left performance behind for nearly a decade, teaching and exploring other paths before finding her way back to music. Teaching fiddle in Kahnawà:ke Mohawk Territory shifted her perspective, and later studying with Frank Gratkowski at Berlin’s Jazz Institut helped develop her current approach, which is rooted in careful observation of the natural world while pushing boldly into experimental territory.

For this album, she gathered musicians she'd long hoped to work with: Gratkowski on bass clarinet and alto saxophone, plus a core of Canada's most inventive players, including Doug Tielli on trombone, Nicholas D'Amato on bass, and Nick Fraser on drums. They bring life to Miller’s varied scores, from fully notated pieces to graphic instructions inspired by seaweed swaying in currents and the slowed cries of seagulls.

Lawrence Peryer: Are you in Nova Scotia?

Nicola Miller: I am. I'm about two hours north of Yarmouth, where the ferry from Maine comes in. I grew up in Ontario, super rural, on a farm where it was a long walk to get to the neighbors. This feels less isolated for me—there are people not too far away. But you still need to drive half an hour to get groceries.

Lawrence: How does Nova Scotia and your sense of place seep into your music?

Nicola: This album relies heavily on place. I live in rural areas, and I spend a lot of time alone, walking in the wilderness and observing. When I get stuck while composing, I go for a walk. It helps because I often see or hear something that sparks an idea or helps me figure out what to do with an idea I'm already working on.

"Buffleheads" is a perfect example. It's about ducks—and I think ducks are romantic, though not everybody agrees. These little black and white ducks travel in groups, and there's never one specific leader. Their order changes as they glide through the water. I watched them for quite a long time and developed the concept of writing a melody using intervals gathered from their grouping numbers. I wrote it in unison, but any player can move ahead of or behind another player at anytime. The tempo is flexible. Then, at any point, one duck will dive underwater, and usually, the others follow, disappearing for quite a while. That became the improvisation section, a textural shift.

Lawrence: I wanted to ask you about "Buffleheads.” I was curious about the balance between structure and improvisation. What a fascinating inspiration.

Nicola: The hardest part was remembering to return to the melody exactly where we'd left off after the improvisation. Once you get into an improvisation, it's challenging to recall your exact place.

Lawrence: Now that you've given me that context about the role walking plays for you, I'm curious about "Poplar." I listened to it before we got on, and it's one of my favorite pieces.

Nicola: There's a similar story behind "Poplar." For a long time, I would walk by this house owned by a retired woman who didn't live here—we have a lot of that, where people have these big fancy houses but don't live here full-time. This particular house has been empty for as long as I can remember. A big field beside it leads into the woods through a path, and you can come out the other side to complete a full loop. Now people have bought the house, which is nice that they're using it, but we can't walk there anymore.

In the spring, right on the edge of the field, there are poplar trees with a deep forest behind them. The poplar trees have these leaves that emerge in the most amazing color—bluish-green, silvery, and soft. They have a completely different texture and feeling than what's behind them. It's almost like a screen. So I wanted to write this typical chorale, a beautiful melody, and then have it obscured by noise, which is the opposite of what I was seeing.

Lawrence: I understand that you use different approaches to notation. When you walk into the room for a session or rehearsal, what do you tell the ensemble or musicians?

Nicola: My education was originally in traditional jazz, so the charts I would see always consisted of melody and chords. Theo Bleckmann and Uri Caine came here in 2018 to do a composition workshop, and I was lucky enough to participate. They challenged my perception of what jazz could look like on the page. Since then, I've been fascinated with how composers write and what they put on paper. The people in my band also all write using alternative notation quite a bit.

The album ranges from fully notated pieces like "Living Things" and "Night Crawlers," which are through-composed with sections of free improvisation, to "Poplar," which was a notated melody and baseline with instructions. "Buffleheads" follows a similar approach. "Seagulls" has notes in groups with instructions, and "Seaweed" was based on a video I took and is accompanied by instructions.

Lawrence: What might an instruction say?

Nicola: For "Seaweed," I had this video of a slow-moving wave coming in where you could just see the top of the water. As the wave came, you'd see this colorful seaweed lift with the water and then fall. After the wave left, there were still effects rippling through. That was quite random and hard to predict.

Originally, the instruction was that the drummer would represent this wave, causing the rest of us to stir with after-effects. But when that didn't quite work, we tried again, affecting each other's movements. You need to answer as soon as somebody plays a line, and it's all minuscule. We were looking at the seaweed's fine joints and how if one joint moves, the others will.

Lawrence: It's interesting to hear about the role of environment and stimuli. Do you have inspirations you draw from, or do you just constantly take in sound and react to it?

Nicola: It's a bit of both. My education originally came through the traditional jazz world, and I always had trouble fitting into that. When I went to Berlin for my master's degree, I was exposed to many new concepts and ideas and people defying genre boundaries, including Frank Gratkowski. He exposed me to many things—for instance, Messiaen uses bird calls. It's not uncommon.

When I returned to Nova Scotia from Berlin, I found myself getting more work with contemporary classical musicians than with jazz performers. I was exposed to new ideas. Seeing how they put their ideas on paper was exciting because traditional notation often doesn't do the job.

There's also a composer here named Amy Brandon, who is amazing. She's shown me a lot through her work, letting me play her pieces and seeing how she approaches composition. I'm incorporating these influences while questioning: if I'm walking and hear seagulls crying, and it's so complex and beautiful, how can I put something that intricate on a page so people can read it within a reasonable rehearsal timeframe? When you're working with jazz musicians, the answer is often an instruction, whereas it might be a different approach with contemporary classical musicians.

Lawrence: I would love to hear about the challenges you experienced in the education system. From your biography, I understand this caused you to step away for a while.

Nicola: I grew up in the country and had an incredible high school music teacher who encouraged me to move forward, exposed me to jazz, and encouraged me to pursue it. I went to Humber College in Toronto, a great school, but that was the early 2000s, and things were different for women then. Although I think it's still hard for women in jazz particularly, back then, it was especially challenging. There were a few female instrumentalists at the beginning of my time there, but after the first year, I was the only one in my year.

I want to be careful about this because it wasn't all bad—I had some great teachers who respected me. But often, it was about fending off male teachers trying to take advantage and questioning whether my worth was about what I was playing or that they were hitting on me. The answer I came away with was that I didn't have anything to offer musically, at least not in that world.

I pivoted and was introduced to the Tranzac Club in Toronto, a beautiful place with a real community where experimental music happens. I tried doing folk singer-songwriter stuff, but that wasn’t me, so I stopped altogether. I had some nice adventures—I lived on the west coast on Gabriola Island and traveled to India and Scotland. But by the end, I was questioning what I was doing with my life.

I began teaching and working in a Mohawk immersion school at Kahnawake, just outside Montreal. I loved being there and was fully embraced by that community. I learned so much and am super grateful for that time in my life. But when I moved to Nova Scotia—my partner is a boat builder, so it made sense for us to come here—suddenly, it was like the rug had been pulled out from under me because I didn't have that sense of purpose anymore.

I started taking fiddle lessons because there was a lot of fiddling around here. I realized I was always practicing—it felt so good to practice. I thought, "I should switch back to the saxophone." Then Uri and Theo came here, and they treated me like I deserved to be making music, treated me like an equal. It felt so good and different from what I'd experienced when I was younger.

Lawrence: Do you see differences between jazz or creative and experimental music versus the contemporary classical world? Are one more open or closed than the other?

Nicola: I love jazz. What I always struggled with were the expectations from people I came across—you've got to play fast, you've got to play like Charlie Parker, you've got to have all these tunes memorized, you've got to be able to play them in any key, and if somebody starts playing, you need to quit. It was so intimidating, and I'm not good at playing fast. I've never been. My brain doesn't work that way, and I just don't hear music that way.

Finding a place where I was okay with that took a long time. Much of this was due to Frank Gratkowski acting as my mentor. I learned that expressing yourself and who you are is important. You’re doing what you should do as long as you do that. But it took a lot of hard work to get there.

Lawrence: I'm very curious about the mentor-student relationship in music. How does a mentor challenge you or push you to find your voice?

Nicola: I can't say enough good things about Frank. I met him pretty quickly when I got to Berlin. I went to see Lina Allemano, who is from Toronto and spends part of her time in Berlin. I knew her somewhat; she was playing with Mike Reed, a drummer from Chicago. They were playing again the second night with Frank, and it was such an amazing show. I heard Frank and thought, "What is he doing?" He was playing flute, clarinet, and saxophone, and I had no clue how he was making these sounds happen.

A friend told me he was teaching at the school I was attending and had an ensemble. I talked to him and asked if I could join, even though I wasn't supposed to because I was in the master's program. He said, "Of course, just show up."

I hadn't really played free improvisation much before. We played, and he sat quietly, then said, "All you do is diddly diddly. You don't listen. It was terrible." I knew right then I was going to listen to this man. He was right.

Lawrence: You knew he was right?

Nicola: Yes. And it was nice just to have it be so straightforward, not this "Oh, nice try," but just to be told how it was. I respected that. So, I kept going to the ensemble and asked if I could take private lessons with him.

He cared so much about teaching me. I would do this once a month, and he would come prepared, saying, "I was thinking about you, and I was thinking we should do this." He always said, "You doubt yourself. I can hear the doubt in your playing. Don't question yourself. Just play, just listen. That's all you need to do."

Lawrence: How did Frank and the other players become involved with Living Things?

Nicola: I was thinking about applying for a grant—we have a pretty good funding body here in Nova Scotia. If I'm asking for money, I want to ask for people I've always wanted to do a project with. Nick D'Amato, I play with all the time, so he was immediately included. Then I thought, imagine if I could get Frank Gratkowski here—that would be such a treat. I put it in the application to see what would happen. I knew Frank could read anything and improvise brilliantly, so right away, that's a dream to compose for because you don't have any limits.

Doug Tielli, I’ve known him for quite a long time, and he is unbelievable. He plays a lot of free jazz and experimental music on the trombone. He doesn't consider himself a jazz musician, but he can do it—in my mind, anyway. I knew that by writing for him, I'd have access to all these sounds on the trombone, anything I could imagine.

Nick Fraser, I didn't know quite so well. Strangely, I got to know him more when I was in Berlin because he was living in Canada but was there a lot on tour. I'd always loved his playing. I think I first saw him playing with another friend of mine, Eric Chenaux, a guitar player, singer, songwriter, and experimental musician. Nick's playing just blew me away. I knew that I'd be able to write for him, ask him to improvise, and always be satisfied.

It was a treat to have them and know there weren’t limits to what I could write. I didn't have to worry about them being upset if there weren't chord symbols written down. On "Night Crawlers," I wrote a drum part, which was difficult. I don't think Nick played it fully, but he did his version. Even taking the time to read that and figure out what it was—not every drummer will be willing to do that for you.

Lawrence: Who's in your pantheon? Who inspires you in terms of, if you could pick up the horn and be in their boots, who does that for you?

Nicola: I don't think there's anybody now whose boots I'd want to be in other than my own. However, in terms of big influences, Lee Konitz was the first. I remember being at Humber College and discovering him—I think the first album I heard was with Brad Mehldau and Charlie Haden. When I put it on and heard them playing "Alone Together," I thought, "Jazz can be like this?" It was amazing—so much space and delicate, and his ideas were so creative. That sent me on a Lee Konitz obsession for quite a while. There was a time when people would say, "Oh, you sound like Lee Konitz," which was always the biggest compliment, although I don't think anybody would say that now.

And then Eric Dolphy, of course—what can you say? It almost doesn't matter what notes he plays. When I listen to him, it's not even about that. You feel this beautiful energy, and it's coming at you in full force. Eric Dolphy is incredible.

I love Henry Threadgill’s approach to writing and philosophy so much. I was just reading an interview the other day where he was talking about transcriptions. He said you've got to be careful with that. You're putting somebody else's words in your fingers and muscles, and that's dangerous because you can't get that out. You lose your voice. That's a pretty controversial view.

Lawrence: You mentioned earlier that you still get slightly jittery or nervous. Do you recognize that as something you can bring to the music and channel into the music?

Nicola: Yes, and now it's not debilitating, so that's helpful. I empathize with people who struggle with nerves because it's a full physical thing—you can do all the mental work you want, but when your hands are shaking and your heart's racing, that's pretty difficult to manage. But again, I'm grateful for being put through a process that forced me to overcome it.

Jam sessions for me are the height of anxiety, but when I was in Berlin, I thought, "If I can go to a jam session, I can do anything." So I did. I would go, and it was awful. It was a horrible experience. "Let's play this tune now, and let's do it fast"—and it's like, I don't know the tune, I can't play that fast. But I did it. I forced myself to do it.

Now, I lead a jam session for some adult students who started playing in their seventies. It's great. We have Nick D'Amato, who's on the album, and another Nick, Nick Halley, who plays drums here. He used to play drums for James Taylor and now lives down the road. He's an incredible jazz drummer. So once a month at this small-town pub—a place you would never suspect—we have this session where people of all abilities can come out and play. The main thing I hope it has is that everybody should feel comfortable, regardless of their skill level or age. And I think so far it's been successful.

Lawrence: Do you ever play outside?

Nicola: Yes, I do. It's so beautiful. I grew up on a farm, and when I return there, especially in the summer, I go down to the barnyard where there's a cement pad where the chicken coop used to be. You can sit there and look over this huge field. The amount of birdsong in the air that you can just sit and interact with or try to imitate—it's really inspiring.

Visit Nicola Miller at nicolamillersaxplayer.com and follow her on Instagram and YouTube. Purchase Nicola's album Living Things on Bandcamp.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments