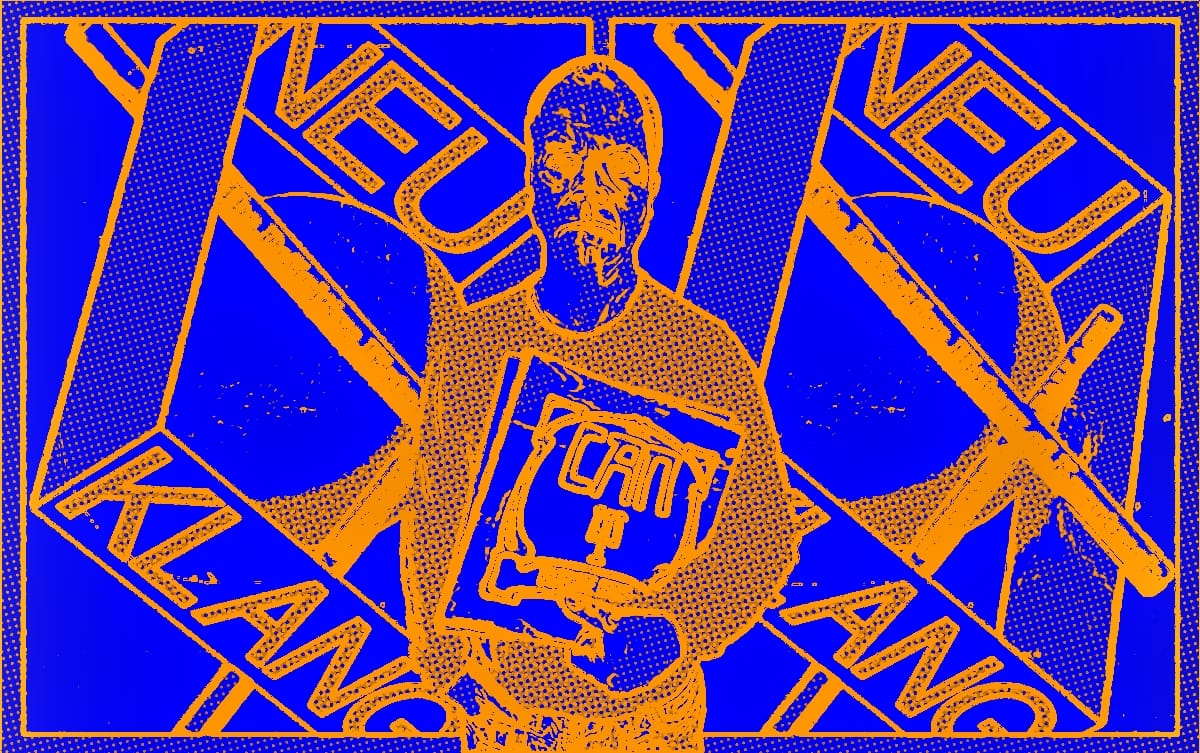

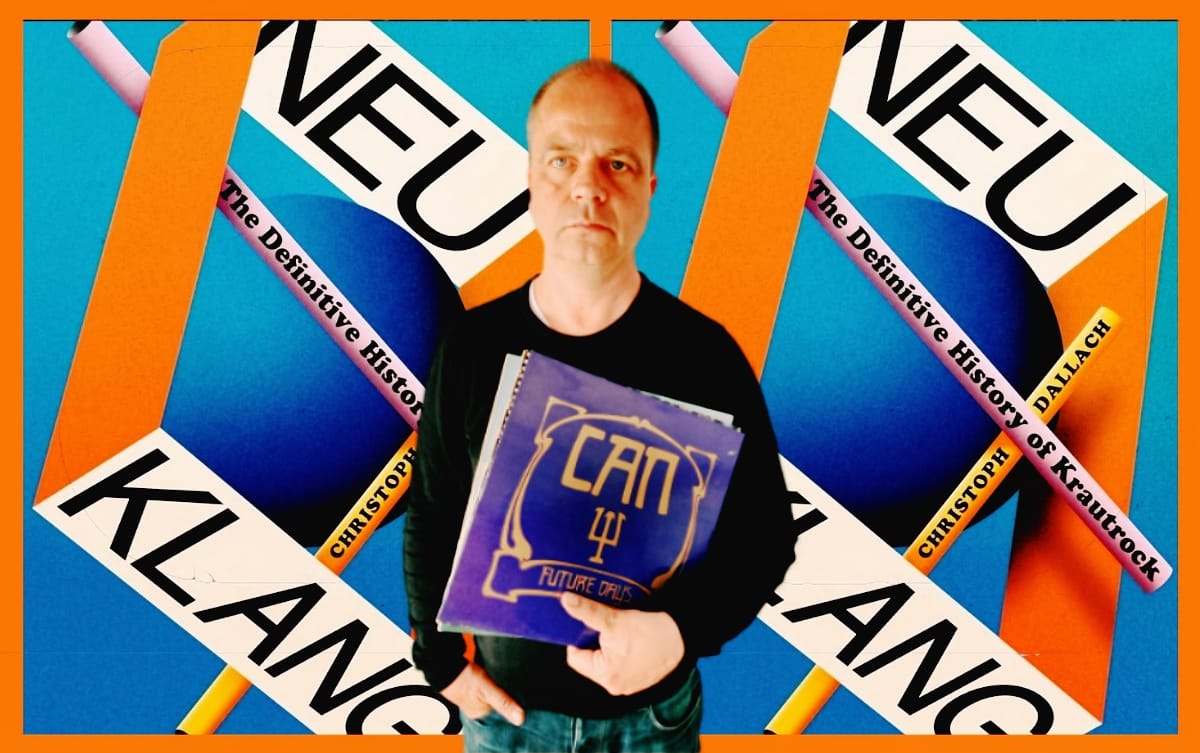

The echoes of post-war German experimental music continue to reverberate through modern sound. New releases featuring synthesizer drones, motorik rhythms, and cosmic guitar jams permeate the bins of the hippest indie record shops. Christoph Dallach's Neu Klang: The Definitive History of Krautrock excavates and explains the persistence of this sonic occurrence and gives voice to the pioneers who crafted an entirely new musical language from the rubble of mid-20th century Germany. Through extensive interviews with members of Can, Neu!, Cluster, Tangerine Dream, and others, Dallach assembles an extensive oral history that pulses with the same revolutionary energy that defined the movement itself.

Against the backdrop of 1968's global youth movements, West Germany's musical revolutionaries grappled with a uniquely complex inheritance. Their rebellion wasn't simply against conservative social norms but against the weight of recent history itself—against Nazi teachers still in classrooms, against the silence of traumatized parents, against the saccharine escape of Schlager music that dominated the airwaves. What emerged was a musical expression that rejected both Anglo-American rock conventions and Germany's musical traditions in favor of something that felt beamed in from the future itself.

Through Dallach's careful curation of voices, a portrait emerges of artists determined to find what Can's Irmin Schmidt calls "a third way"—neither purely avant-garde nor conventionally popular, but something that existed in the spaces between established forms. Dallach uncovers a larger story of a generation attempting to forge a new cultural identity from the ashes of the old. This led to a loosely aligned movement of bands creating sounds that would influence everything from ambient music to post-rock, from techno to experimental electronic music. Krautrock and its rebellious spirit are here to stay.

Christoph Dallach was a recent guest on the Spotlight On podcast, discussing Neu Klang: The Definitive History of Krautrock and its topic in entertaining detail. Many incredible and discoverable bands are name-checked, along with thoughts on the future of Kraftwerk, the culturally influential upheaval of 1968, differing views on the term 'Krautrock,' how the young confronted their parents about the war, and, of course, the role played by the ubiquity of Schlager music. This extensive conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

'I Don't Belong in This Book'

Lawrence Peryer: Tell me about your decision to choose the oral history format for your book.

Christoph Dallach: I've always liked that form. I remember when I started this job at the beginning of the '90s, there was an oral history about Andy Warhol's Factory, where everyone remembered how it was. What I like is the idea that people remember things differently. I don't believe there's one truth.

People don't lie. They just have a different recollection of how things went. For example, in my book, [the band] Faust—four guys who aren't too keen on each other and stopped talking years ago—but they all green-lighted their quotes and remember things differently. But I think none of them was lying.

I always found that interesting. There's this famous Japanese movie by Kurosawa about a stagecoach robbery in a forest. After the robbery, everyone involved remembers how it went, and they have four or five very different recollections.

I've been conducting interviews at my job for over thirty years. I like that form, but I never liked it when someone told me how they saw it. So, I always try to get people to tell me how they did it.

Lawrence: And there were some notable holdouts in the book?

Christoph: Yes, of course. Kraftwerk, they just don't talk, but they rarely do. I spoke to Ralf Hütter long ago and asked someone who knows him quite well—not many people know him well, but we have a friend in common. I asked him to ask Ralf, and he said, "I don't belong in this book. Kraftwerk are not a rock band."

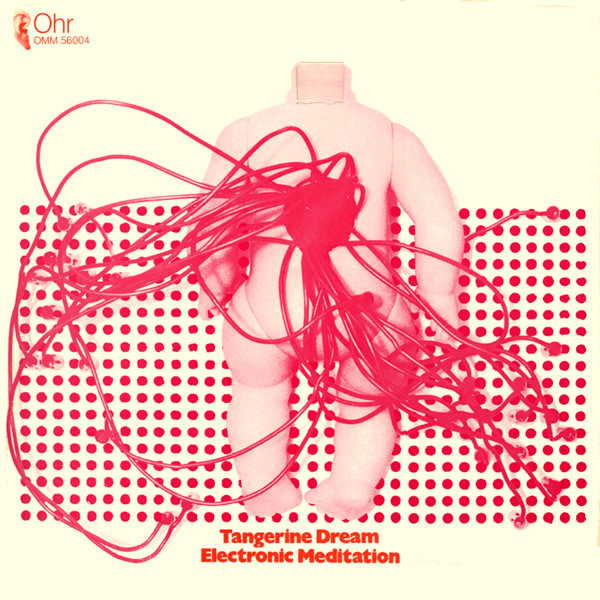

At some point, he's right. And at another point, he's wrong. Because, like Tangerine Dream, they're not a rock band, but they belong in this book.

The other person who's missing is Edgar Froese from Tangerine Dream. And with him, it's a bit sad because I love Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream the same way. Growing up, I often listened to Tangerine Dream, so I wanted them to be in the book. Edgar, if you will, was the band. He was the main character in Tangerine Dream.

He said yes, and then we had a date. But for some reason, it didn't work out. I had to cancel on short notice, and we said we'd find another date. Before we had the other date, Edgar left this planet. I was really sad about this because I think he left a gap. But through the magic of Discogs, I checked the names of people who worked with Tangerine Dream. I found Steve Schroyder, whose stories I loved a lot. What he says about the early Tangerine Dream was beautiful. And I have Peter Baumann.

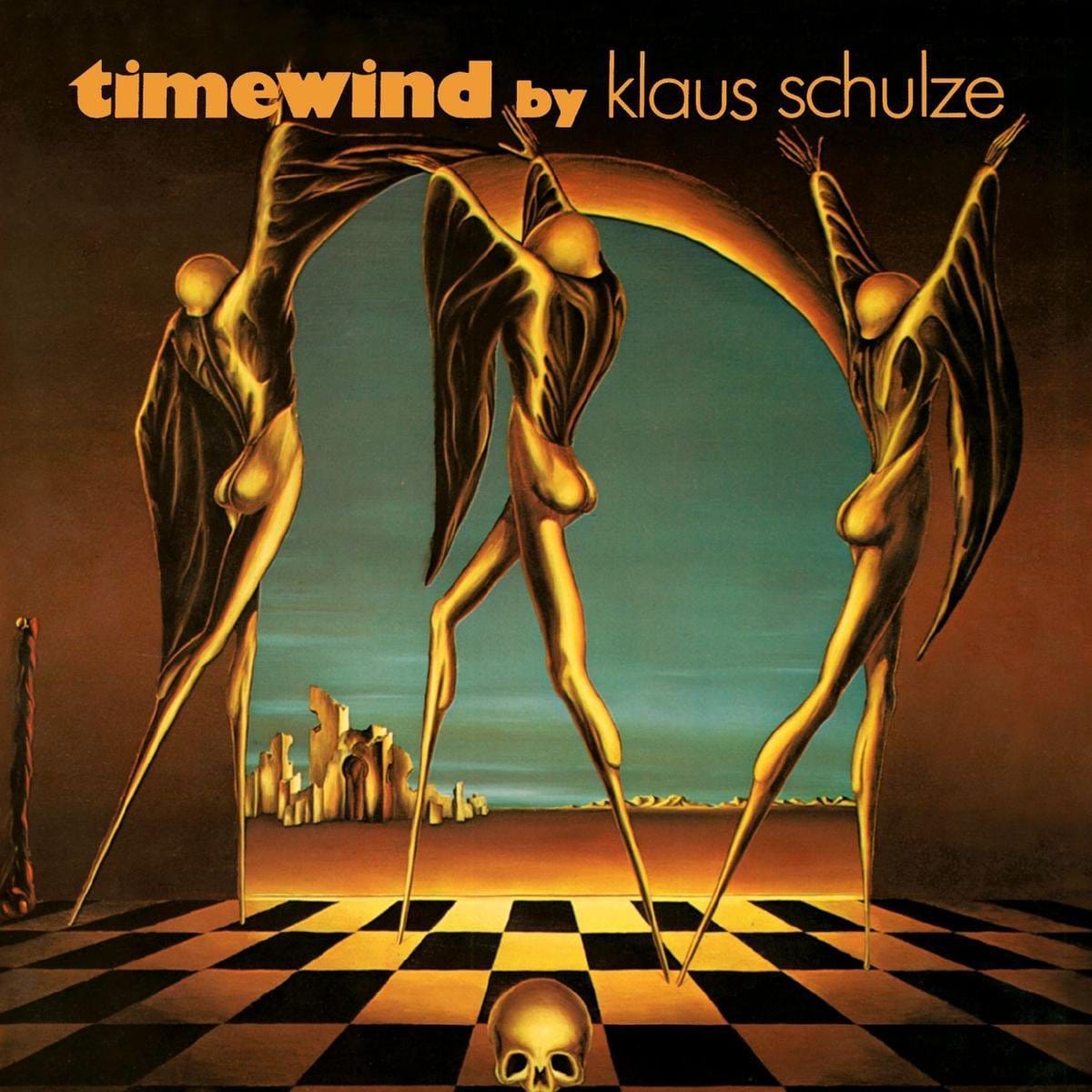

The most important artistic, in my opinion, Tangerine Dream version was Peter Baumann, Christopher Franke, and, of course, Edgar Froese—the Virgin Years, as people call it. The era from '72 to '76, when they were with Virgin Records. And I have Peter Baumann in the book, which I'm happy about. But otherwise, I have to say, I have everybody I wanted.

A Robotic Way to Continue

Lawrence: To stay with Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk for just a moment, what do you make of the continuation of Tangerine Dream? As a fan, is that okay with you?

Christoph: In all honesty, for me, it's a mistake. I get the idea that his widow said Edgar gave his blessing to a couple of other young people to continue with Tangerine Dream, which somehow is okay, but on the other hand, it's very strange. Because now you have three people who otherwise don't have any connection with Edgar.

I went to a show last year in Hamburg. Yes, it was good. They tried to reproduce the Virgin years, which I like a lot. It was very interesting, but the whole time, I thought, "It's wrong—they should change the name."

Christopher Franke and Peter Baumann are still alive, who were very important for Tangerine Dream. I think one of them should be part of this to make sense. This is like if Paul McCartney would say to a couple of young boys, "You could be the Beatles when I'm gone; you have my blessing." They're not the Beatles. And these guys, for me, with all due respect, are not Tangerine Dream. They should change the name. What they do is good, but it's not Tangerine Dream.

Lawrence: As the classic rock generation of people leaves us, it's interesting to ponder that it's possible that that music, big portions of it at least, is at risk of disappearing if it's not kept alive in a performance context. Who should be performing that music live?

Christoph: But at what price is the legacy kept alive? I think you should accept when the story is over. I grew up being a Queen fan when I was young. The new singer does a great job, but it's not Queen. He's not Freddie Mercury. Brian May is fantastic on guitar. And the show I saw had beautiful moments, but it's not Queen. It's something else. I left after twenty minutes. I think one should accept when the story is over.

Lawrence: Do you think Kraftwerk will continue after Ralf?

Christoph: That's a very good question. I don't know. Gene Simmons once told me that he imagines Kiss going on as holograms. Gene Simmons, for me, is a genius because his idea of the band appearing as masked comic characters gives them every freedom they want.

Kraftwerk are a bit the same. This whole robotic thing—they could find a robotic way to continue. I think in the end, it's just Ralf who must decide if he wants the story to continue or not. I have no idea, but I think having four robots is possible.

I went to this strange ABBA show in London where you have these holograms. It was beautiful and scary at the same time. I attended the one-year anniversary and sat beside the original members on the balcony. When the hologram characters on stage said thank you, all the lights went to the balcony, and the original ABBA members stood up and said hello to the audience. So it was the ABBA musicians, around 70 or 80 years old, and very young copies of them on the stage. It was highly impressive. ABBA opened a new door. And this may be possible for Kraftwerk, too.

Neu! at the Flea Market

Lawrence: To Ralf's point about "we're not rock,"—it's clear to me that the American and British commentators in the book are less comfortable with the "kraut" part of krautrock than the German commentators are. The Germans object much more to "rock." [laughs]

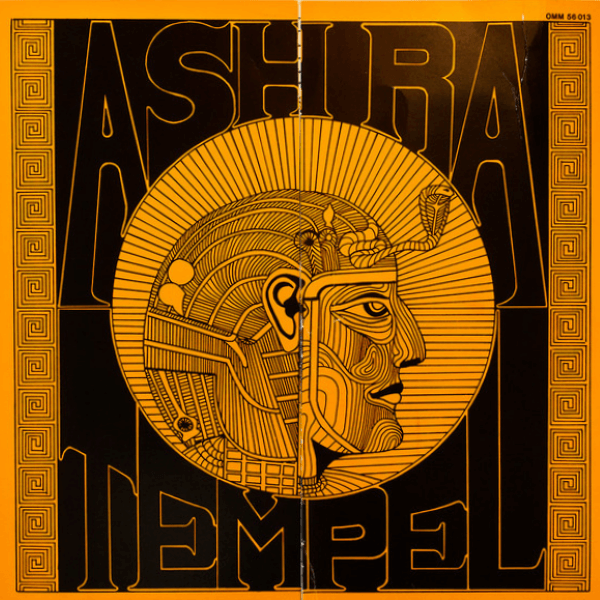

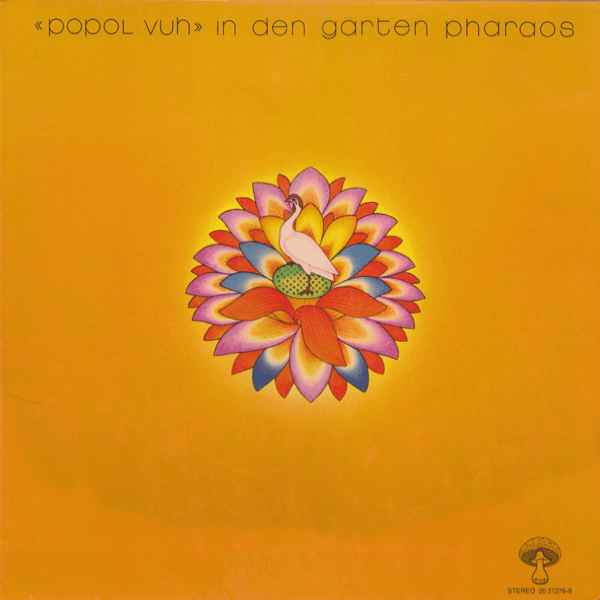

Christoph: They insist they're not rock bands, which is true in 90 percent of cases. For example, you might call Can a rock band. In many ways, they are. But in the end, what Can are is unique. But Tangerine Dream are not a rock band. Popol Vuh are not a rock band. Kraftwerk aren't a rock band. And so on.

In my book, Brian Eno says he hates the term "kraut" because it comes from the war. If I remember correctly, Daniel Miller of Mute Records says he still hates it, and he's the one reissuing all the Can records. The British considered it a disrespectful term for Germans, so they were more critical of it than the Germans, who now see it as a joke.

Nigel House, who runs the Rough Trade Shops, says it's nonsense because bands like Tangerine Dream and Can have nothing in common besides being German. But putting them in one section of your record shop helps to sell these records. So if you go to Rough Trade and you're looking for a classic Tangerine Dream, Amon Düül, Faust, or Neu!, you go to the Krautrock section and find it. That is a straightforward, good answer.

Lawrence: You might not walk over to the experimental rock section or the electronic avant-garde section or whatever it is, but having them all filed under "Krautrock" gives them a framing.

Christoph: Growing up, Julian Cope's book about Krautrock, Krautrocksampler, was important to me. Maybe 60 percent of the bands he mentions I'd never heard of. But back then, there was no chance to get these records. He wrote about it beautifully, and I would have loved to listen. But back then, finding a Popol Vuh record was impossible. Finding a Cluster record—impossible.

Lawrence: Even in Germany?

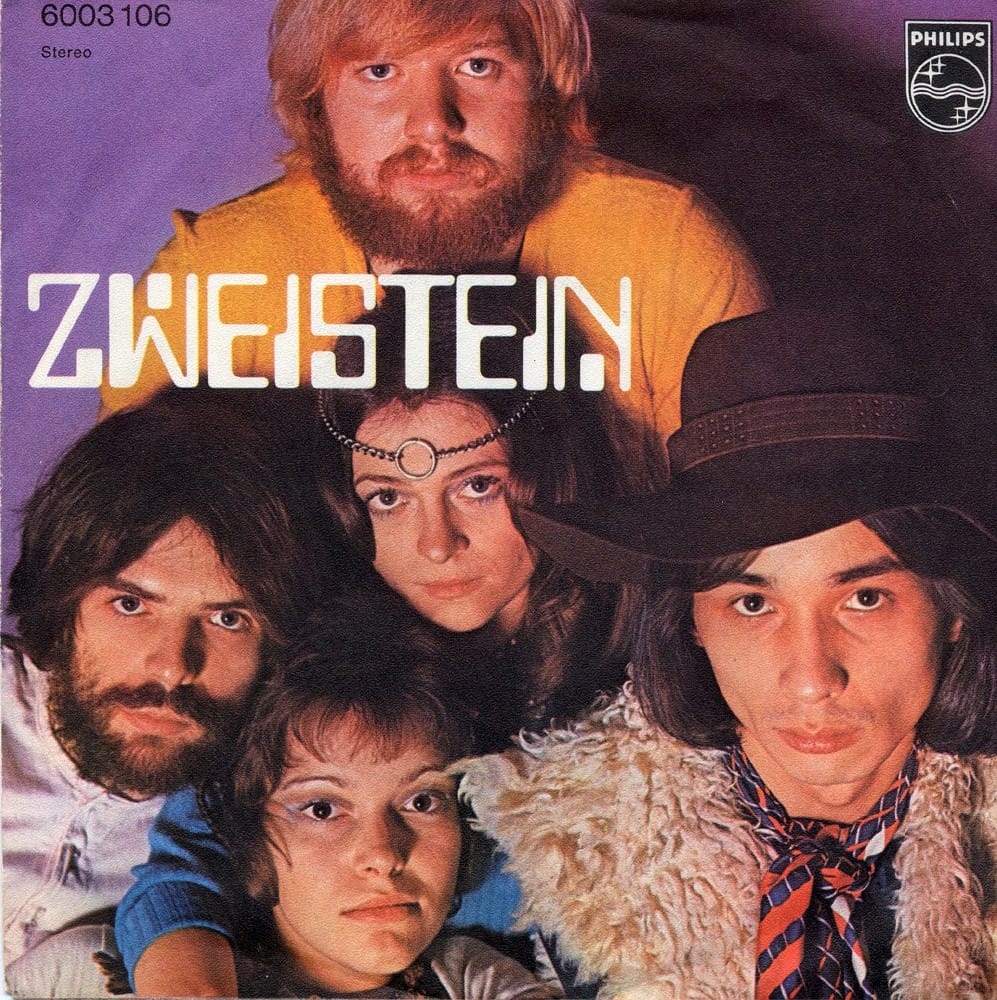

Christoph: Even in Germany. Nowhere. You found Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream, of course. If you were lucky, you found Neu! at the flea market. But you couldn't get most of it. And these days, like it or not, you have Spotify or YouTube, and you just Google "Cluster" or "Harmonia," and you can listen to it the next second.

And even rare records like Zweistein and Suzanne Doucet, which are rare to this day—you could listen to them. If you see her mentioned in my book, you Google it, and two clicks later, you can listen to that album. And if you like it, you can go to the Krautrock section at Rough Trade or somewhere else and get these records. Most of them are available now.

Some of the bands are still touring. I just saw that Guru Guru, for example, are playing in Hamburg next week, which is fantastic. And so it helps these musicians get discovered by a very young generation.

Lawrence: Were there any new revelations or new insights that came to you that you didn't have at the beginning of the book?

Christoph: Well, most people in Germany believe that Kraftwerk invented electronic music in Düsseldorf. But then I learned about Thomas Kessler's electronic studio in Berlin. Thomas Kessler was an interesting avant-garde composer from Switzerland who had the studio with the first synthesizer they ever had in Berlin in '71. He showed Edgar Froese from Tangerine Dream the first synthesizer.

Edgar Froese's Tangerine Dream were a blues rock cover band. Then Edgar went to the Electronic Beat Studio in Berlin, and bands like Ash Ra Tempel, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, and Agitation Free all went to that studio. If you look at when records were released, electronic music was produced in Berlin before Düsseldorf, which people in Düsseldorf don't want to hear. But that's probably historical truth, which I learned while working on this book.

Starting at Zero

Lawrence: So I want to talk a little bit about the cultural context of the music. There's this notion of transcending, reconciling, or escaping the past—the past being the World War II era of their parents. So there's the sociopolitical aspect of it. There's also the post-war culture of Schlager music being the only thing left. [laughs]

Christoph: It was mainly Schlager and jazz. Jazz was always there, even in Germany. Before rock and roll, jazz was the music of freedom. Jazz was forbidden in the war under the Nazis. Some tough kids just played and listened to jazz, and they went to jail for listening to jazz. It's unbelievable, but it's true.

The political aspect of these Krautrock musicians is very important. I learned a lot through the interviews I conducted for this book. Although I grew up in Germany, I never thought too much about growing up in the '50s and early '60s. I started to understand how horrible it was to grow up in then. People like Jaki Liebezeit, the Can drummer, he was being shot at. Hans-Joachim Roedelius went to a bunker because bombs were going down. So they remembered the war.

And then growing up in destroyed cities, with fathers being absent, or coming back and just being quiet. Not wanting to talk. They must have gone through horrible things. There were a lot of Nazis, don't get me wrong, but if you went to the war, maybe you were very young, you didn't have any choice, and it must have been super horrible.

So, you had Nazi teachers, Nazi policemen, Nazi people in all positions of society. Some were frustrated that things didn't go how they wanted. I heard horrible stories of teachers in schools being unhappy about the outcome. The people in my book were the ones who opposed them. When some Nazi teacher said horrible stuff, they said, "What are you talking about?"

Like Irmin Schmidt of Can, who had a tough time in school because he was young and bright. He said that he liked some of the teachers and then found out about them having some position in Hitler's army. He said, "How could you do it?" and made it public. He had to leave school a couple of times, and he fought with his father a lot about his position in the Third Reich.

Most of the people in my book were opposed. They didn't say, "Oh, yeah, that's how it is." They fought with their families and their fathers. They decided they had to find a new way and answered with art. There were new ways of literature, painting, and music.

They were the ones who started the new Germany. In some way, the Second World War ended in Germany in '68 because a whole generation said, "No, that's enough. Shut up, and now we are taking over." That's when a young, new Germany started, and there were tough fights. I found this touching.

There's no Krautrock sound, and these bands couldn't be more different—again, like Tangerine Dream and Can—but a whole idea keeps this together—starting at zero and creating something new. Not simply to be original but to get rid of the past and the Third Reich. They needed to make it clear they were very different and needed a new way.

This is what they all have in common—the urge to start at zero. They didn't want to sound like the Beatles or the Stones—and not because they said the Beatles or the Stones are bad, but it's not their history. It's not their story. They didn't have the blues because it's not their history. They're not from Nashville. They're not from New York. They're not from London. They're from Berlin, from Düsseldorf, Munich, and Hamburg.

I don't claim that I was the one who coined that formula. That was, in all honesty, Julian Cope. These bands have a different sound. They're not the Scorpions—the sound of the Scorpions could have come from New York, Los Angeles, Boston, or London. But Harmonia, they sound like Düsseldorf or nothing you have ever heard. Kraftwerk, Can, Popul Vuh, or Amon Düül sound like nothing you've ever heard. All these bands are unique, and that's what they all have in common.

Lawrence: We know 1968 was a pivotal year socially and politically worldwide, certainly in Western countries, with the youth movements and a lot of reaction against authority and authoritarianism. How was that manifesting specifically in Germany?

Christoph: There were loads of student demonstrations. Police were going strong against demonstrators, and there were big fights. There was a pivotal moment in Berlin when a policeman shot this one student, Benno Ohnesorg. Three people in my book may have been close by and even heard the shot.

This is a big thing in Germany, the killing of Benno Ohnesorg, who was just peacefully demonstrating. And this is where some parents started thinking, "Maybe our children are right." Even in Munich, which is ultra-conservative to this day, but back then, even more so, everyone started demonstrating. The students started, and there was this general feeling of wanting a different society.

This changed the country radically in a beautiful, positive way. And I think, yeah, in Germany, it was a phase of transition of the young generation taking the old generation out for a fight. Eventually, the older ones accepted that things had to change. And things changed. It was a pivotal historical moment in German society.

Lawrence: I did have questions about Schlager music. What would analogous music be to an Anglo or an American audience? Is it sort of adult contemporary or easy listening?

Christoph: It's easy listening, which is complicated because I like American easy listening. [laughs] In a surreal way, it's even more cheesy. It's a mixture of the Carpenters and Ray Conniff but done in a really uncool way.

The music pretended everything was great after the war: "Let's go into the sun. Let's go to Italy. Let's fall in love." It was everywhere. People didn't want to be reminded of the ugly past. Back then, in a destroyed country, you listened to music that told you everything was great. But the music was horrible and in no way beautiful.

Of course, some of the Schlager musicians were talented. Some were good. However, American easy listening had writers like Burt Bacharach and Hal David, the lyricist. Amazing. So, it's hard for me to compare that to Schlager. Schlager was like the basement for this, and they were the penthouse. Burt Bacharach's music wasn't just easy listening; it's highly complicated. It's amazingly creative.

Lawrence: Sophisticated popular music.

Christoph: Sophisticated pop music, yes. But Schlager music was horrible. The only escape was jazz, and then rock and roll coming over was freedom, too. Bill Haley came over to Germany and found a joyful resonance—a young audience destroying places where he performed out of joy, not because they didn't like Bill Haley. Bill Haley was big here in Germany. Then, the Beatles, the Stones, and so on—it changed a lot. But before that, it was horrible. [laughs]

Purchase Neu Klang: The Definitive History of Krautrock from Faber & Faber, Bookshop, Powell's, Barnes and Noble, or Amazon. Follow Christoph Dallach on Instagram.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments