What do 'It's a Wonderful Life,' 'Star Wars,' 'Back to the Future,' 'The Nightmare Before Christmas,' 'The Lion King,' 'Looney Tunes: Back in Action,' 'Harry Potter,' and 'Stranger Things' have in common?

The answer: One of the most recognizable pieces of music in cinema history… And also one of the least noticed.

Most of the time, anyway.

In the case of 1980s ‘The Shining’, it’s practically synonymous with the film itself, droning over the opening titles and setting a foreboding tone for the events to come.

This piece of music is, of course, ‘Dies Irae.’

Heard at least 245 times in film and television music between 1927 and 2022 alone, it’s one of the most referenced pieces of music in pop culture and the go-to when a composer is trying to set the mood for dark and sinister events.

Let’s dive into the history of this oft-heard but little-known bit of musical brilliance, what makes it so creepily effective, and how it came into such wide use for television and movies from the early 20th Century to today.

Plain Talk About Plainchants

While certainly not among the oldest known musical compositions, ‘Dies Irae’ is likely the oldest and most recognizable one frequently used in popular media.

Pronounced “DEE-ay ZEER-ai” (or thereabouts), ‘Dies Irae’ is a medieval European plainchant. The ‘plainchant’, or ‘plainsong’, was the hallmark of the Catholic Church from its earliest days.

A plainchant is a melodic recitation of a prayer or psalm. The characteristics of a plainchant include Latin lyrics performed without accompaniment as a single line of vocal melody.

And, rather than being dictated by counted-out bar lengths the way we’re accustomed to with music today, the length of plainchants is structured around that of the prayer itself. The rhythm is dictated by the pattern of speech rather than that of the music, in a method called ‘free rhythm.’

Lastly, a plainchant relies on modes, which are ancient Greek variants of traditional musical scales. A mode can be thought of as a scale that starts with any note other than the usual first note of said scale.

Seven main modes were used in musical notation during the Middle Ages, conjuring either a somber or holy feel depending on the mode used.

By way of example, ‘Dies Irae’ is written in the ‘Dorian’ mode, a minor key by today’s standards that makes the music feel grim right off the bat. If you were looking at the keys of a piano, the notes are crammed in right next to each other. And, the notes descend in pitch rather than ascend, literally making the music a downer.

These are all things that our ears don’t like, and we interpret them as morose… Just as intended.

Hellfire and Damnation

So, what does ‘Dies Irae’ translate to for those of us who don’t speak Latin?

It’s a sung prayer about the Biblical end of the world, typically performed during a Requiem Mass to put the dead to rest.

The first two lines of the chant, in Latin, are:

Dies irae, Dies illa

Solvet saeclum in favilla

…which translates as:

The day of wrath, that awful day,

Shall reduce the world to ashes

Some modern translators get poetic by rhyming their English versions:

That day of wrath, that dreadful day,

Shall heaven and earth in ashes lay

Spoiler alert: it just gets worse from there.

But why compose such a dirge in the first place?

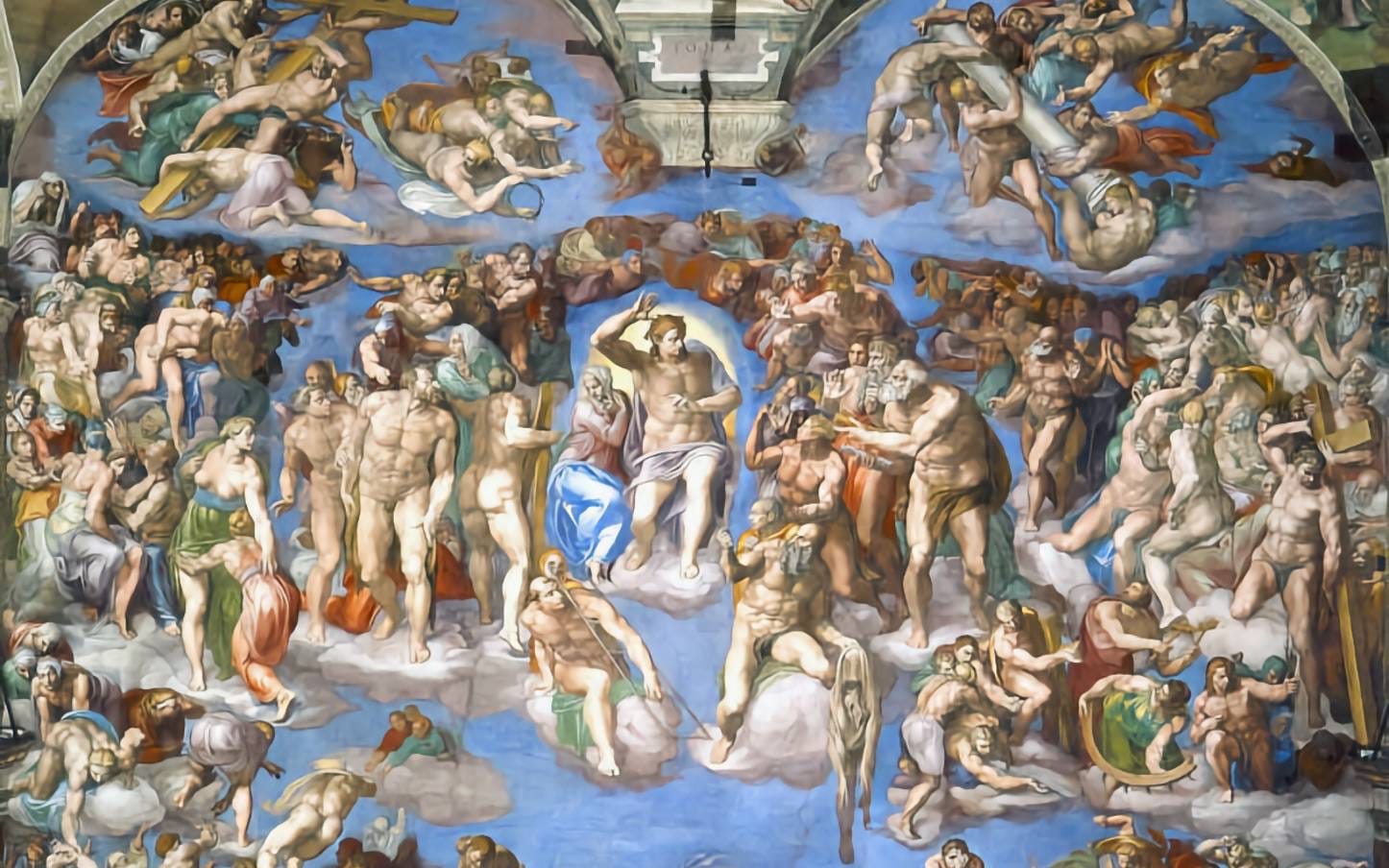

Because existential gloom and doom fit perfectly with the early Catholic Church’s fixation with hellfire and damnation.

As the classical antiquity period shambled to a close, Christianity was elevated as the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380 CE by Emperor Theodosius. This placed it in a powerful position of influence over most of Europe and Asia Minor.

And, as the Western Roman Empire all but ceased to exist in 476 CE, the centuries-long administrative framework provided by the Empire was fractured right along with it.

This made the early Middle Ages a particularly chaotic time to be alive in Europe. Lack of governance plagued the Empire’s vast former territories… And wherever there's a power vacuum, you can be sure there will be people fighting to fill it themselves.

The Catholic Church found itself uniquely situated as a unifying force where there was otherwise little unity. The organizational power of the Church provided structure and much-needed continuity for the populace as the Empire’s borders shriveled inward.

In doing so, the Church became the default repository of knowledge from the ancient world. Early medieval rulers relied on having “learned men” from the clergy to advise them.

This also meant the Church was pivotal in the day-to-day lives of the population in a way that's hard to imagine in today’s largely secular society… Nearly every facet of daily medieval life included involvement from the Church in some way.

And the beliefs of the vast majority of that population reflected a terrifying and unpredictable world of divine judgment. It was a worldview of near-constant suffering and death from war, famine, and disease.

With certain doom waiting to strike from every shadow, where else would the populace go for reassurance than the Church?

But there wasn't a great deal more the Church could offer except the promise of a better life after death.

So why not lean into it?

Some En-chanting Evening

The origin of ‘Dies Irae’ may stretch back so far that it treads on the toes of antiquity itself… And presents a tangle of traditional beliefs and historical evidence, making it no small challenge to tease one out from the other.

Some sources maintain that Judeo-Christian chants, in their most basic form, existed concurrent with the lifetime of Jesus Christ, thereby dating to the 1st Century CE. Religious chanting itself wasn't a new idea, so it would be more surprising if early Christians didn’t chant… Though there may have been a risk in drawing attention to themselves, what with the Persecution and all.

Pope Gregory I is traditionally believed to have taken up the reins with chants sometime in the 6th Century CE. The story goes that he was inspired by the Holy Spirit in the form of a white dove who sang in his ear.

And in doing so, Gregory lent his name to these plainchants as ‘Gregorian Chants’... But not during his lifetime, nor indeed for a long time after. Others hold that Pope Gregory II was a more important contributor in devising what became known as ‘Gregorian Chants’ in the 8th Century CE.

The historical record agrees with the development of Gregorian Chants between the 8th and 9th Centuries CE, specifically prompted by Charlemagne in 789 CE. Charlemagne was a forceful ruler and advocate of Christianity who was keen on unifying the Carolingian Empire with standardized religious practices. One of the ways he achieved this was by requiring all chants to be performed in Latin as opposed to disparate regional languages.

For hundreds of years, Gregorian plainchants formed the backbone of Catholic liturgical music. They eventually crowded out all other Christian chant styles by the 12th and 13th Centuries CE.

And this is where ‘Dies Irae’ comes back into the picture.

A Good Day to Die

‘Dies Irae’ is believed by some to have been created by Pope Gregory I himself in the 6th Century CE. But the lyrics bear a strong resemblance to a late 4th Century CE Latin translation of the Biblical book of Zephania.

If it's true ‘Dies Irae’ was inspired that long before the lifetime of Gregory I, this would place it squarely around the time Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire.

But, while it may indeed be much older, the chant as we know it today is commonly credited to the Franciscan friar Thomas of Celano in the 13th Century CE.

Unfortunately, just when Gregorian chants seemed to be at their peak, culture was shifting and musical tastes were changing along with it.

Whereas Gregorian chants were sung with a single melody (though with many singers), a new-fangled style known as ‘polyphony’ was gaining popularity. With the addition of harmonies, chants were no longer confined to a single melody.

As the devout Catholic years of the Middle Ages gave way to the Renaissance and the rise of Protestantism in the 16th Century CE, the Church felt pressured to overhaul its music. After the Council of Trent sessions between 1545 and 1563 CE, clumsy attempts to force Gregorian chants to conform to the newer styles resulted in them not really being Gregorian chants any longer.

The old-fashioned chants were effectively made obsolete.

But ‘Dies Irae’ outlived them all.

A Hymn of Death Gets New Life

‘Dies Irae’ and Gregorian chants in general languished in obscurity for at least a hundred years… And, when ‘Dies Irae’ was rediscovered, was reborn with all new trappings.

The first known quote of ‘Dies Irae’ after the demise of Gregorian chants was in Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s ‘Mass for All Soul’s Day’ from around 1670. Music had entered the Baroque period by this time, but those iconic first four notes are unmistakable. And, while it retained its choral quality, was more sweeping in scope with the addition of an orchestra.

Many more famous quotations were to follow from some of history’s great Classical composers. But, while the essence of ‘Dies Irae’ is present, it’s not usually included in its entirety. Instead, it often appears as a launching point for compositions that dance around the chant rather than shout it.

A few of the highlights include:

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Requiem Mass in D minor, Circa 1791

- Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14, Circa 1830

- Franz Liszt: Totentanz for piano and orchestra, Circa 1849

- Giuseppe Verdi: Requiem Mass, Circa 1873-1874

- Camille Saint-Saëns: Danse Macabre, Op. 40, Circa 1874

- Sergei Rachmaninoff: Symphony No. 1 in D minor, Op. 13, Circa 1894-1897

- Modest Mussorgsky: Songs and Dances of Death, Circa 1894-1897

None of these esteemed composers forgot the doomy origins of ‘Dies Irae’, with each adding their own spin to the deathly theme.

‘Dies Irae’ hasn’t been forgotten when it comes to film music, either.

The first example from cinema’s earliest days is the 1927 score for Fritz Lang’s silent film ‘Metropolis’, composed by Gottfried Huppertz.

As time has marched on, the nods to ‘Dies Irae’ in cinema have, for the most part, boiled it down to its first four famous notes… And even then, sometimes disguised in such a way that you probably don’t notice it unless you’re looking for it.

But you certainly feel it.

You feel the dread of Jason and his Argonauts as they prepare to battle the Children of the Hydra’s Teeth.

You feel Luke Skywalker’s pain and rage when he discovers the burnt remains of his aunt and uncle.

You feel Elsa’s apprehension at leaving all that’s familiar to pursue a dangerous path into the unknown.

Not even video games are a safe haven from the dark portents of ‘Dies Irae’, including lending its name to one.

And there have even been calls throughout the last few decades to bring ‘Dies Irae’ back into regular practice within the Catholic Church… Vatican II pulled it in 1970 to try to make the Church’s message more positive.But you can’t cheat death forever.

Terror Becomes Timeless

As prolifically as it's used, you may wonder how many examples are intentional versus coincidence… And that’s a fair question. Just because it’s the oldest doesn’t mean that other composers couldn’t have stumbled onto those same notes in that same order by accident. Some reviewers find it even where it wasn’t intentionally quoted by composers.

But maybe that simply serves to emphasize its timelessness.

‘Dies Irae’ is a magic brew of audible sorrow. It reaches into obscurity and summons the primal terrors that humans have both fled and honored from time immemorial.

And there’s no reason to think it will stop now.

###

FAQs About This Article

wherein an AI reads the article and suggests a few questions that remain unanswered...

Q: Why did the Vatican II pull 'Dies Irae' in 1970 from regular practice within the Catholic Church?

A: The decision to remove the "Dies Irae" sequence from the Requiem Mass in the Catholic Church stemmed from the reforms initiated by the Second Vatican Council (Vatican II), which took place from 1962 to 1965. Vatican II sought to modernize and renew various aspects of Catholic liturgy and practice to better engage with contemporary society and promote greater participation of the laity in worship.

One of the key documents produced by Vatican II was the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, known as Sacrosanctum Concilium, which was promulgated on December 4, 1963. Sacrosanctum Concilium outlined the principles for the reform of liturgical practices within the Catholic Church.

Regarding music in the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium emphasized the importance of preserving and fostering the treasury of sacred music while also allowing for the incorporation of new musical forms that are in harmony with the sacred liturgy and the spirit of the times (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 112). The document encouraged active participation of the faithful in the liturgy and recommended the use of vernacular languages in addition to Latin.

As a result of the reforms initiated by Vatican II, there was a revision of the Roman Missal, the liturgical book containing the prayers and texts used in the celebration of the Mass. The revised Roman Missal, promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1969, included changes to the Order of Mass and the texts of various liturgical prayers, including those used in the Requiem Mass for the deceased.

The removal of the "Dies Irae" sequence from the Requiem Mass was part of this broader effort to simplify and streamline liturgical texts, as well as to promote a greater sense of hope and consolation in the funeral liturgy. While the "Dies Irae" sequence had long been a traditional part of the Requiem Mass, its vivid imagery of judgment and wrath was seen by some as inconsistent with the pastoral tone desired for funeral rites in the modern context.

Instead of the "Dies Irae," the revised Roman Missal provided alternative texts for the Requiem Mass, including passages from Scripture and prayers that emphasize themes of mercy, hope, and the resurrection of the dead. These changes reflected the desire of Vatican II to make the liturgy more accessible and meaningful to contemporary Catholics while remaining faithful to the Church's rich tradition.

Q: How did 'Dies Irae' evolve from its origins in Gregorian chants to its modern-day usage in film and other media?

A: The evolution of "Dies Irae" from its origins in Gregorian chants to its modern-day usage in film and other media reflects a fascinating journey through the history of music and culture. Here's a breakdown of how this iconic motif has evolved over time:

1. **Origin in Gregorian Chants:** "Dies Irae" originated as a medieval Latin hymn, likely dating back to the 13th century. It was part of the Catholic Requiem Mass, sung during funeral services and reflecting themes of judgment, death, and the afterlife. As a Gregorian chant, it was performed in monophonic plainchant style, characterized by a single melodic line without harmonization.

2. **Influence of Classical Music:** During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, composers began to incorporate "Dies Irae" into their compositions, expanding its musical scope beyond the confines of plainchant. Famous composers such as Mozart, Verdi, and Liszt used the motif in their Requiem Mass settings and other compositions, adding harmonies, orchestration, and thematic variations.

3. **Integration into Romantic and Modern Music:** The 19th and 20th centuries saw further adaptations of "Dies Irae" by composers of the Romantic and Modern eras. Works such as Hector Berlioz's "Symphonie fantastique" and Sergei Rachmaninoff's Symphony No. 1 incorporated the motif, often as a symbol of doom, fate, or impending catastrophe. The motif's dark and ominous connotations made it a powerful tool for evoking dramatic tension and emotional intensity in music.

4. **Utilization in Film and Media:** With the rise of cinema in the 20th century, "Dies Irae" found a new platform for expression in film scores. Composers began to use the motif to underscore moments of suspense, horror, or impending danger in movies. From classic films like "The Shining" to modern blockbusters like "Star Wars," the motif's association with death and judgment made it a fitting choice for enhancing the atmosphere and narrative impact of cinematic scenes.

5. **Continued Influence in Contemporary Culture:** In addition to film, "Dies Irae" has also made its way into other forms of media, including video games, television shows, and even popular music. Its recognizable four-note motif has become ingrained in the cultural consciousness, often serving as a shorthand for themes of mortality, fate, or supernatural forces.

Overall, the evolution of "Dies Irae" from its origins in Gregorian chants to its modern-day usage in film and other media reflects the enduring power of music to evoke emotion, convey meaning, and transcend historical and cultural boundaries.

Comments