The sound of steel-on-steel guitar caught a teenage Cary Baker's ear on Chicago's Maxwell Street in 1970. Drawn to that haunting resonance, he discovered Blind Arvella Gray, a street performer with a Dixie cup safety pinned to his lapel. His rendition of "John Henry" seemed to stretch endlessly through the bustling marketplace. This encounter ignited a lifelong fascination with street musicians—performers who transform public spaces into impromptu stages.

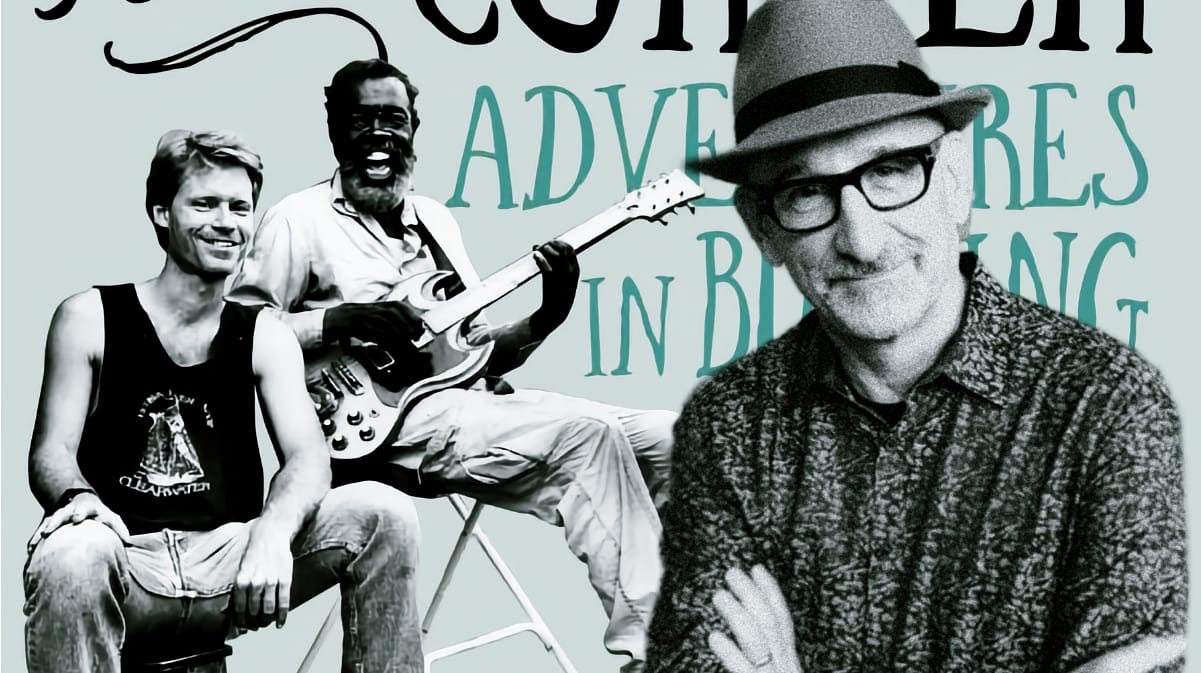

After four decades of navigating the music industry as a publicist for labels including I.R.S., Capitol, and his own firm Conqueroo, Baker has returned to his first passion: writing. His debut book, Down on the Corner: Adventures in Busking and Street Music, published by Jawbone Press in November 2024, assembles stories from over one hundred musicians who pursued audiences on sidewalks, subway platforms, and seaside boardwalks. Baker explores how these impromptu performance spaces shaped generations of musical innovation from the blues pioneers of Chicago’s Maxwell Street to the doo-wop groups who harmonized on urban corners.

The book's narrative weaves through unexpected connections between famous artists and street performance—Mick Jagger thanking Ramblin' Jack Elliott for a London subway performance he witnessed during a school field trip; Violent Femmes being discovered on the street by members of The Pretenders; and musicians like Lucinda Williams, Elvis Costello, and Billy Bragg who refined their craft through busking. Beyond these recognizable names, Baker pays equal attention to seasoned street performers whose artistic contributions happen outside of recording studios and concert venues.

Lawrence Peryer recently hosted Cary Baker on the Spotlight On podcast for a wide-ranging conversation about Down on the Corner and the fascinating history of busking. The pair also touched upon the street musicians who inspired the book, memories of Chicago’s fabled Maxwell Street, why these public musical expressions remain vital in an increasingly digital world, and how yacht rock might be the antithesis of street music. Listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for clarity, length, and flow.

Metal on Metal

Lawrence Peryer: I’m curious how you initially became interested in street musicians and the early artists that sparked the writing of Down on the Corner.

Cary Baker: I grew up in the Chicago area in the suburbs, a pretty middle-class existence. One day, my father, the son of Eastern European immigrants, wanted to show me Maxwell Street in Chicago, where his parents used to take him. It was a flea market with a sense of community, and he assured me I'd only want to see it once.

We parked near the University of Illinois, walked across Roosevelt Road, and the first thing I heard was slide guitar against metal on metal. We followed the music and found Arvella Gray—a blind, Black, older street singer with a Dixie cup safety pinned to his lapel. He sang a long version of "John Henry," adding lyrics about Maxwell Street.

When he finally took a break, I introduced myself. I was only 16, with a blues radio show on my high school FM station. I asked for an interview. Around that time, I picked up a new publication called the Chicago Reader and thought it would be a good home for my story about this blind street singer. At age 16, I typed up a story based on the interview and sent it to the Chicago Reader. Soon, there it was in print—my first article.

Before long, not only did I want to see Maxwell Street more than once, but I was going there almost every Sunday. There were many street singers there. I was old enough to see Maxwell Street Jimmy Davis, who had made an album for Elektra Records, Little Pat Rushing, and others.

After majoring in journalism at Northern Illinois University, I got a call from a punk/new wave magazine in New York called Trouser Press, asking if Milwaukee was near Chicago. They told me about a band called Violent Femmes, who had just been signed to Slash Records. They played punk rock on acoustic instruments—folk punk—and they were buskers, street singers. I went to Milwaukee, about a 90-minute drive, and interviewed them in the street where they demonstrated their street music.

The third major inspiration for my book came when I moved to Los Angeles in 1984. I walked down Venice Beach Boardwalk and heard a singer who sounded like Otis Redding—a deep, resonant soul voice. It was an older Black man named Ted Hawkins. He was genuinely good. He had been institutionalized, imprisoned, and had a hard life, but he had gotten his act together and played reliably on the boardwalk every weekend.

Ted Hawkins was signed to Geffen Records. He was a street singer who got one album that didn't sell much but got a lot of press. He toured the world—it was the best thing that ever happened to him.

I kept encountering street music at South by Southwest conferences in Austin. Mary Lou Lord would play outside, sometimes joined by Billy Bragg (himself a busker) or Elliott Smith. In New Orleans, I saw Dixieland, blues, and folk buskers in Jackson Square and Royal Street. Those experiences sparked my interest in writing this book.

Lawrence: When you look back at your earliest writing, has your perspective on street music changed?

Cary: I think I initially wasn't sure about the legality of busking. I thought municipal governments might view them as outlaws. But as I experienced New Orleans, Austin, and Venice Boardwalk, I realized they're enriching the experience of being outside. Buskers add life, vibrance, and color to a community. As I interviewed about a hundred people for the book, the consensus was that from subway stations to downtown areas to beach boardwalks, street music is a blessing.

Many cities have explicitly legalized it now. The challenge is getting and respecting performance spaces. I've noticed buskers tend to return to the same areas. One couple in New Orleans told me they would get up at 3 a.m. to hold their space for hours.

I wanted to convey in the book that street singing is an asset—a colorful, cool, vibrant addition to a city.

Anything Not a Stage

Lawrence: How far back does this unbroken chain of street performance go?

Cary: Busking goes back to ancient Greece and Rome. There was a book on busking published in 1981 that’s more focused on street performance in ancient Greece and Rome, Shakespeare in the park, and Benjamin Franklin, who was not only a statesman but occasionally a musician and singer.

My book starts around 1920 with Blind Lemon Jefferson in Dallas and Reverend Gary Davis in Durham, North Carolina, and some pre-World War II blues artists. I also cover an era I was too young for—doo-wop singing groups. I found Jay Siegel of the Tokens, who told me how they performed at Rockaway Beach. There were Black vocal groups, Italian ones like Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, and Jewish ones like the Tokens.

I spoke with Mike Stoller of Leiber & Stoller, who wrote hits for Elvis Presley. He told me, "First, we didn't write doo-wop, we wrote R&B. And second, I never saw groups on street corners, but I heard plenty of them rehearsing in the men's room at the Brill Building," where much of the recording, A&R, and songwriting for that era happened.

So I included men's rooms in my definition of busking—anything not a stage, really. I have beaches, tubes and subways, streets, curbs, riverwalks, and now men's rooms as well.

Lawrence: Non-traditional public performing spaces.

Cary: That's right.

Lawrence: I understand that doo-wop was shaped by the places it was performed—non-amplified music, voices in a circle or line.

Cary: Absolutely. Doo-wop is deeply rooted in the streets. The Dells are a perfect example from Chicago. "Stay in My Corner" and "Oh, What a Night" were doo-wop songs. They added instruments in the studio, but you can hear the street corner influence in those songs. You could imagine them on the streets of Harvey, Illinois, a south suburb of Chicago, where they performed after school.

Lawrence: How did street performance and the Chicago blues sound fit together? Was there a progression?

Cary: Maxwell Street goes back much further than Blind Arvella Gray. He was one of the final artists to play before the neighborhood was gentrified, which I think was an awful mistake. Maxwell Street could have been what Beale Street is to Memphis, Bourbon or Royal Streets are to New Orleans, or East Sixth Street is to Austin.

Maxwell Street was first populated by Eastern European, mainly Jewish, immigrants in the 1940s, but by the late '40s, it had become predominantly Black. You could see a young Muddy Waters playing there. Chuck Berry played there. Little Walter, often called the Coltrane of blues harmonica, played Maxwell Street in the late 1940s.

I heard a funny story from Bobby Rush at the Blues Music Awards in Memphis. He had played a blues bar on Chicago's South Side all night, loaded his equipment, and went straight to Maxwell Street. Walking down the street was B.B. King, not yet a superstar in the early 1950s. Bobby Rush knew him and said, "Hey, B.B., you want to sit in with me?" B.B. said, "I'd love to. It'll cost you 50 bucks, though." So they played for a couple of hours and made 55 dollars in tips. Fifty went to B.B., and Bobby Rush and his band split the remaining five dollars. That's his busking story.

Not Expecting Stardom

Lawrence: Can buskers make a living, or are they solely doing it as a hobby?

Cary: It is definitely a living. When I finally saw Blind Arvella Gray's apartment, I was delighted that he lived in relative comfort for a street singer living on quarters and dimes thrown into his Dixie cup. He didn't live in splendor but had a very nice Chicago-style brownstone apartment.

Many buskers are savvy business people. Nowadays, it's not just about quarters or dollar bills thrown into guitar cases. It's QR codes, PayPal, Venmo, and social media. "I'll be playing in Boston Commons between one and three today. Come down. Here's my barcode." People might even pay in advance. It's become a livelihood.

Lawrence: What about performers who move back and forth between club careers and busking? You mentioned several such artists in the book. What kept them returning to that life?

Cary: One of my favorite stories is about Fantastic Negrito, who has won about three Grammys. Real name Xavier, he’s from inner-city Oakland. He developed an act that sounded a bit like Prince with some hip-hop elements and got signed to Interscope Records in the late 1980s. But it didn't work out for Xavier. He got dropped from the label and went back to Oakland to become a pot farmer. Still missing music, he would go out to the streets of Oakland and play. There, he discovered a different sound and persona. Instead of being Xavier, somewhat like Prince, he became Fantastic Negrito playing folk blues, going back to his roots.

He wasn't thinking about performing acoustically until he heard himself busking, which he was doing purely for pleasure and passion, not expecting stardom. But that finally elevated him to winning Grammys in the blues category and touring successfully.

Lawrence: You've shown that this isn't just a New York and London phenomenon but a global one. What have you learned about common elements of street music worldwide?

Cary: You can find street musicians in Sydney, Beijing, Singapore, and many places. However, I limited my scope in the book to North America, including Canada, and Europe, because many key buskers I focused on were from these regions, including American expatriates.

I spoke with Billy Bragg, who told me that although he now plays major festivals and theaters, if he doesn't get a sound check, it's no problem. He learned to wing it on the streets of London, so he can wing it on stage with just a bit of tuning.

I interviewed Americans who went to London and Paris to busk. Mojo Nixon, who sadly died shortly after I interviewed him, told me he wanted to join The Clash after college. He went to Britain and started playing in the London tube.

Madeleine Peyroux, a jazz singer with several excellent albums, was raised by a bohemian, hippie single mom who took her to Paris during childhood and to Cannes for the festival, basically telling her, "Sink or swim. Sing for these people." She performed in front of Parisian cafes, which is how she developed her skills.

Madeleine also told me that busking saved her and probably many others during the pandemic. Living in New York, she would go into the streets where it was safe enough, at a distance, to perform. She missed playing, and it kept her creative juices flowing. For people feeling isolated when all concerts were canceled, having that human contact with a busker was life-saving on both sides.

Lawrence: What about the dangers of street performance? There’s a courage to put yourself out there in a quasi-legal environment. There's an element of risk because you don't always know how tolerated it is, especially in an unfamiliar town. I worry for them—their money's on the ground, are they vulnerable?

Cary: Mary Lou Lord shared many stories about being an attractive young woman in the London tube or French subways. She described a suspicious-looking one-armed man who eventually urinated in her guitar case. After that, she felt she'd seen everything.

I'm sure some get robbed—it's easy to snatch hard-earned money from a musician's guitar case. Street performers face many risks.

Peter Case is a respected singer-songwriter who was previously in the new wave band the Plimsouls and, before that, the Nerves. After high school, he hitchhiked from Buffalo to San Francisco—a dangerous journey even when hitchhiking was safer than now. He arrived in San Francisco homeless.

Despite coming from a middle-class background, he was a rebel following his dream. He found an abandoned car in a junkyard to sleep in, found a place to shower, and busked daily on Fisherman's Wharf or near City Lights Bookstore. He met fascinating San Francisco characters. Allen Ginsberg once came out of City Lights and spontaneously joined him for a session, though they'd never met before.

Spontaneously Imperfect Music

Lawrence: What aspects attract you to street music? How do you compare it to other types of studio-produced music?

Cary: I watched the yacht rock documentary recently, and it struck me how street music is the antithesis of yacht rock in many ways. What I love about street music is its spontaneity, its low fidelity, its accessibility—anyone can do it. If you're good, you sometimes develop a following. And so much depends on luck.

The Violent Femmes might still be performing in Milwaukee if Chrissie Hynde and James Honeyman-Scott of The Pretenders hadn't had time after their soundcheck, noticed the band, and invited them to open for their opening act. Similarly, Ted Hawkins being discovered by a Geffen executive—that's just luck. There are countless buskers in every city whose names you'll never know. I made a point on Maxwell Street to learn their names—Little Pat Rushing, Maxwell Street Jimmy Davis, Blind Jim Brewer.

Arvella Gray meant the most to me and guided me throughout this process. I like to think I helped him and helped busking a little by writing that Reader article and producing his record. It wasn't a bestseller—I don't care. This book won't be a bestseller either—I don't care. Both were created out of love for homespun, lo-fi, and spontaneously imperfect music.

I enjoy all kinds of music, including the polished sounds of Steely Dan and Michael McDonald from that yacht rock documentary, but there's something special about street music that captivates me. I'll sit and watch a busker for hours.

Lawrence: Do you think about a taxonomy of street musicians in terms of people making original music versus those just entertaining to earn money?

Cary: Regarding original versus cover material, I was at a book festival that coincided with a farmers market. A busker was playing electric guitar with a backing track. I gave him a dollar but wondered, "Does this really count?" Some people are playing their hearts out, whether cover songs or originals, but this seemed to be playing by numbers. But I can’t walk by a busker without throwing a dollar in. These days, I'm very conscious of good busker karma.

Lawrence: You mentioned the changes to Maxwell Street, which connects to broader changes in American cities and their impact on cultural groups and the arts. You also noted the cultural significance of having music on the streets and how cities have come to recognize that. There's a spectrum between tolerance and active support. To your knowledge, what places today are particularly good for buskers, and which seem more hostile?

Cary: Subways are probably challenging, though commuters appreciate the entertainment that brightens their journey to work.

I get the sense that New Orleans genuinely appreciates what they have, though it was hard-fought. I interviewed an attorney who advocated for buskers and someone from a musician advocacy group specific to New Orleans. The city has recognized that much of its color, interest, and tourism revolves around music. Visitors expect to hear everything from Dixieland to R&B to Trombone Shorty's unique sound. The city has taken stock, and busking is permitted now—you can set up within reason.

Some cities have regulations about decibels, amplification, or drums, but many are realizing they're enriched by street music. In an era when you can order almost anything online, what brings people downtown? Many work remotely—why go to Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica or South Congress in Austin? It's the experience, the community of being among other people. What enhances that more than performance and music? I've seen poets and orators, but music particularly makes you smile and feel better about humanity, your day, and being in a diverse urban environment.

I wish Chicago would reconsider Maxwell Street. There is a makeshift new Maxwell Street on Des Plaines Street, but it didn't impress me when I visited. There were musicians representing various ethnicities, but it lacked the character of the original with its decrepit buildings, famous deli featured in The Blues Brothers, and the record store where you could buy Little Walter 78s for a dollar. Experiencing that at age 16 was priceless, and I probably wouldn't have if not for my father, who thought he was "taking me slumming." It changed my life.

I'm a city kid living in a gated desert community now, far from urban streets, but when I walk through Palm Springs and see an old man playing "Lady of Spain" on accordion, I smile and give him a dollar. I love street life and walking through downtowns. Long may there be downtowns, and long may there be busking.

Purchase Down on the Corner: Adventures in Busking and Street Music from Jawbone Press, Bookshop, Powell's, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon. Follow Cary Baker on Bluesky, Instagram, and Threads.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments