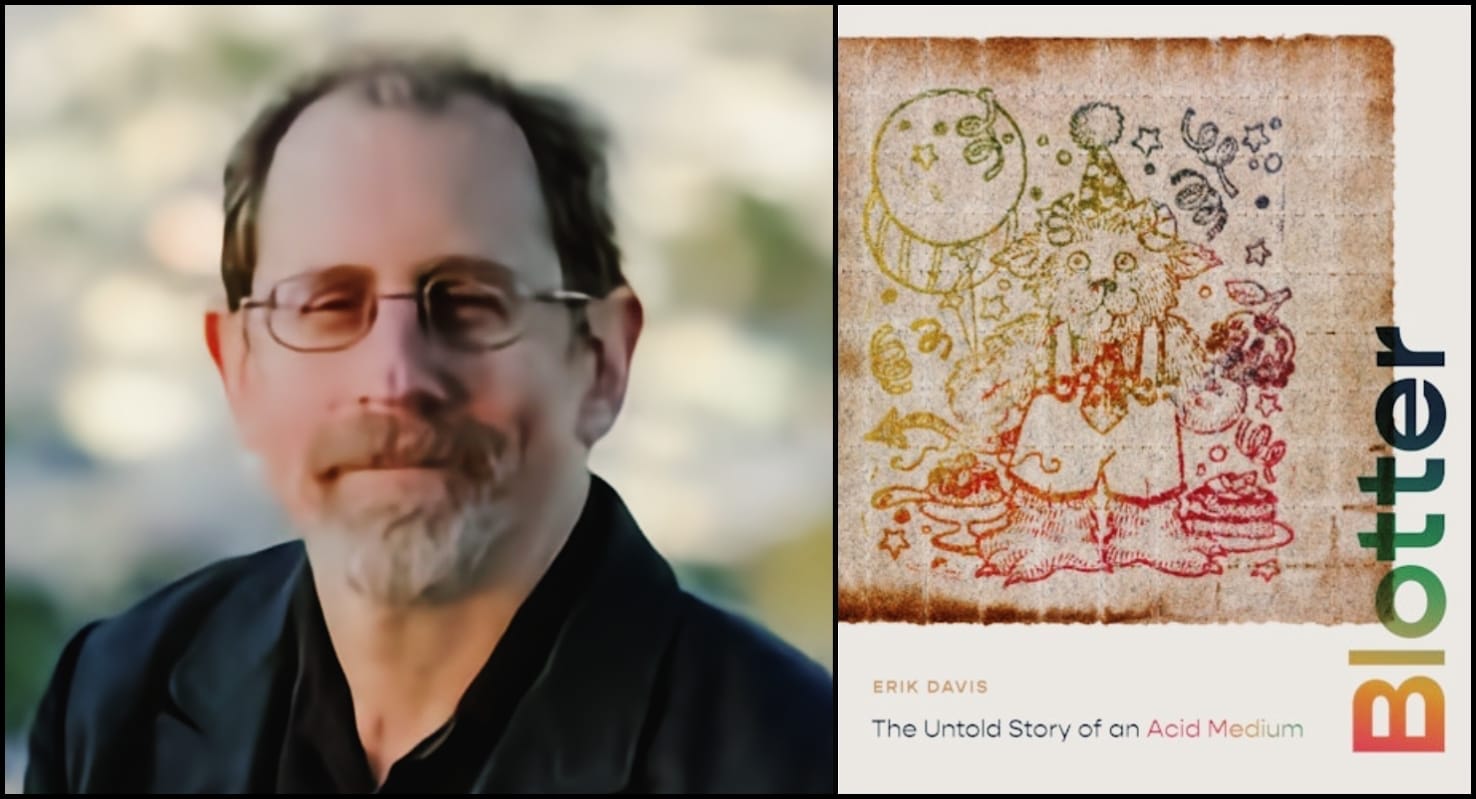

Acclaimed author Erik Davis has spent his professional life researching and writing about the connections between technology, spirituality, and counterculture. His approach is unique because it combines a rigorous academic approach with a deep, experiential understanding of his topics. His 1998 book, TechGnosis: Myth, Magic, and Mysticism in the Age of Information, quickly established Davis's name in the countercultural zeitgeist, effectively documenting how alternative spirituality and technological movements influenced each other.

Davis has since increasingly explored psychedelia and its effect on modern history, art, and popular culture. His research has proved valuable in chronicling these radical mind-shift changes and placing them in a historical context. The books High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies and, most recently, Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium have overturned stones on important facets of American culture that are often unrepresented, or worse, misrepresented.

Davis's fluidity with moving from institutional spaces to underground communities makes these books special—he maintains scholarly precision while exhibiting a knowing and entertaining perspective on the scenes he's researching. This openness and active participation in the scenes Davis follows helps earn the rare trust of influential figures like Mark McCloud, the art curator of The Institute of Illegal Images and the backbone of the tales that make up Blotter.

What's particularly compelling about Blotter is it's so much more than a book about perforated LSD art. Davis examines how spiritual seeking, criminality, the art world, and bureaucratic opposition interweave to create complex cultural narratives—whether he's analyzing DEA documents about the LSD trade or documenting the stories of underground artists and chemists. On the Spotlight On podcast, host Lawrence Peryer discussed these heady concepts with Davis while also interacting with nostalgia and experiences with interconnected scenes, such as those associated with The Grateful Dead. The highlights from this conversation are excerpted below and have been lightly edited for clarity.

The Outlaw and the Sheriff

Lawrence Peryer: I devoured this book. I wasn't expecting such strong feelings of nostalgia, and I'm still living in its emotion. Something that triggered it was when you caused me to look up the DEA's blotter index. Just looking through that was like looking through a photo album.

Erik Davis: Yes, it's a remarkable document.

Lawrence: There's this idea that "the outlaw and the sheriff are often more alike than not." I've usually had this sense that the DEA are some of the most interesting characters regarding information about drug subcultures.

Erik: I was interested in that quote, which I use in the book. The DEA wrote in the early 1990s about how the LSD manufacturing subculture has an unusual mystique and is not like other criminal operations because the profit motive does not solely drive it. There's a sense of a crusade and higher values along with financial motivation. It reads just like a subculture historian like me would write.

The Blotter Index is one document made by a character who focused extensively on blotter and tried to study it as intensely as possible, understanding where different materials were coming from and analyzing the perforation marks to identify continuities.

The Blotter Index is only part of this decades-long DEA study reflected in the issues of Microgram. This internal document, now mostly available online through the 1990s via Erowid, required much effort to collect. It involved friendly librarians, unnamed people inside the DEA, and Alexander Shulgin.

These documents are fascinating because they're internal. They're mostly filled with chemical analysis and discussions about analyzing and comparing street drugs. Still, they have this opening section about weird developments in the field from across the nation and sometimes globally. There are reports of new formulations, drug delivery devices, and new production runs, with extensive information about blotter.

Interestingly, the DEA is the first collector of this otherwise ephemeral and designed-to-be-consumed form. They paradoxically help sustain the memory of this evanescent cultural form.

Lawrence: It represents bureaucratic earnestness—if we do this, we will do it thoroughly and professionally. Although they distinguish or acknowledge the ideological aspect of the LSD trade, they don't make allowances for it or say, "Let's not be as harsh about this as we are with, say, the crack epidemic," which was happening in parallel. There are limits to the empathy or understanding you want for them.

Erik: They were going after the LSD trade in the late '80s and early 1990s when it arguably wasn't impacting society negatively. There weren't many emergency room disasters or people jumping out of buildings. Still, acid always galled the DEA in a particular way because these were members of their own class, sometimes people who were better educated than them.

It's an upper-middle-class culture of intellectuals rather than an underclass they can lord over. It's not like the crack epidemic, where they control racialized populations, which is part of what drug prohibition has been about throughout American history. Instead, you have these university kids who could be working for Wall Street, and they couldn't catch them.

Except for Leonard Pickard and a few others, most of the high-level families that continue to produce LSD crystal in quantity and quality remain undisturbed. That is incredibly galling to these agents. Operation Looking Glass, an early '90s campaign that targeted the Grateful Dead scene, emerged because when the Dead became hyper-popular in the late '80s and 1990s, the DEA legitimately saw that this would involve a resurgence and return to a more mass psychedelic culture, which was true.

Interestingly, this paralleled the rise of rave. The "In the Dark" and mega stadium transformation of the Dead happened roughly around the time rave started in England. By the early 1990s, there was also a psychedelic renaissance inside electronic dance music.

The DEA played many nasty games, especially because so many low-level dealers ended up doing serious time due to how they weighed the materials. One of the things that motivated me when thinking about the criminality and religiosity of the acid underground—which, to me, is the most interesting conjunction—was this relationship between enforcement and ideology.

I saw an incredible interview with Joel Blaeser, an acid dealer in the '80s Dead scene. After getting arrested, he ended up in a supermax prison because he was in the wrong place at the wrong time. His reflection on the experience was fascinating because it revealed moral, ethical, and religious values, even though he wasn't religious. He spoke about what inspired him about the Dead scene—the sense of celebration, love, and light—and how those values carried him through his prison experience.

When he was busted, they essentially tortured people to try to get them to turn on those higher up the chain. He didn't turn; you have to draw on serious moral sources to do that. It's the kind of decision that martyrs make. In a way, it is a kind of martyrdom—taking on an unjust law and enforcement agency that's criminalizing a relatively benign substance.

That's how I got to know Mark McCloud, who owns and collects the extraordinary archive behind my book Blotter. Mark and I united in preventing an unnamed Ivy League professor with important friends from joining the psychedelic intelligentsia. Mark had a particular issue with him because he was an informant who, when pressured, not only informed on people but tried to set up innocent individuals. Jon Hanna and I wrote a sarcastic account of this man for our underground community.

Mark read that piece, and we bonded over our shared ethics. You need to trust someone like me to sit with you for months, hearing tales proximate to criminal activity, including stories about people still alive. My ability to recognize and affirm those values is partly how I wrote this kind of book with my background in elite education while maintaining the trust necessary to tell these stories.

Lawrence: Is Microgram still being published internally at the DEA?

Erik: I believe so. I think it's still called Microgram. Recent examples didn't have as much street information at the front as they used to. The chemical analyses are much more sophisticated now, with color images—the earlier ones were like zines.

Other Possibilities Emerge

Lawrence: When I was in sixth grade, we all got a flyer to take home warning our parents about dangerous drugs that would make kids jump off buildings. I remember it vividly almost fifty years later—this hysteria. It reminds me of other subcultures that have that same weird paranoid interaction with authority, like UFO subcultures or non-mainstream religions. They're all threatening because they cause people to question consensus reality.

Erik: That's generally one of the more agreed-upon readings of why the crackdown on LSD was so significant—the drug represented the capacity to undermine conventional values and personality structures. So much of what maintains a society are inherited values, practices, and assumptions about how the world works. If you have something that can erode, suspend, or deconstruct these assumptions, that's dangerous from society's perspective because you're opening up new forms.

I'm not a psychedelic utopian because these new forms aren't necessarily better, and sometimes they're worse. In the 1960s and early '70s, there was a real faith that powerful trips—face-melting 500-microgram breakdowns or 1,000-microgram breakdowns—were great because they could clean you out. They would strip away that old personality and prepare you for a fresh new day. I always think of the Sun card in the Rider-Waite deck, with the naked child on a horse with blonde hair—that's such a hippie idea that if we can just shed these corroded adult war machine selves, something natural and pure will emerge. But that's not true. Other possibilities emerge, but they're not necessarily as morally coherent as that.

We include an example of one of these hysterical letters in Blotter. Many were from different parental agencies, similar to the PMRC stuff but earlier. The hysteria became so extreme that the DEA itself had to make a public statement saying, "No, dealers are not targeting children directly."

One nice thing about this book is that I mostly avoided these larger sociological questions. I focused on these physical objects, giving the story a nice tangibility. Whether something happened in 1976 or 1978, it did happen, and here's what it looks like. Here's what we know about how the blotter makers worked, what they worked with, and how that related to other countercultural crafts and print technologies.

Timothy Leary plays a minor role because he's not making blotter. He might appear on some blotters or sign some, and that's part of the story. But the humble blotter gives you another line in. I was inspired by Jesse Jarnow, who helped edit the book and wrote Heads, a social history of psychedelic culture emphasizing smaller players and scenes rather than the famous narratives.

As the boomers fade, finding other stories—particularly more social stories of scenes, unknown individuals, and collective practices—becomes incredibly valuable. These will help people navigate this new cybernetically inflamed, VC-fueled psychedelic renaissance, which will be extremely confusing once the simple hype proves inadequate to address the challenges inherent in this mystery tradition.

Bound Up with Perforations on Paper

Lawrence: One thing that clouds the work of being a collector or interested bystander in the blotter art world relates to vanity blotter. Because it's such a criminal-adjacent and underground field, there's no objective definition, even when fine artists get involved. It's not a form that requires specific paper—there's a tradition of vegetable ink and offset printing, but it's not necessarily defined as "this is blotter art, this is not." Does it have to be perforated to be blotter art?

Erik: It's simultaneously a blessing and a curse. Blotter art as a collectible object emerged in the late 1990s, around 2000. Initially, these were pieces of blotter, many from the street but usually undipped, signed by psychedelic luminaries. The images themselves were from the street.

Then, people started printing new ones not intended for the street, just as vehicles for signatures or collectibles. In that form, perforation is required—not because it's needed to make acid on paper valuable, but because that's what blotter is.

The size has varied, including the size of the hits, even in the vanity blotter world. But beyond that, there hasn't been quality control or development of a critical apparatus to rigorously distinguish between valid and invalid forms of the art.

There's been a lot of low-quality material, both in terms of images, paper, and printing, that has been bought and sold online because you can't see or feel the paper digitally. While some individuals and outfits have maintained very high quality and developed their criteria, there's plenty of room for copycats and inferior work because there isn't the framework you have in other art forms.

It maintains its underground quality even as a non-drug delivery device. There's a great quote from Matthew Rick, who runs Shakedown Gallery and has been selling for almost twenty-five years: blotter is essentially contraband, so it will never be purely assimilated. Disney might do a skateboard deck, but they'll never do a blotter edition. It maintains this outsider quality that, for historical reasons, is bound up with perforations on paper. This limits its appeal but also makes it interesting.

It's affordable, too. A new, beautiful blotter edition on nice, hand-perforated paper might be twenty or thirty dollars. Signed editions might cost fifty dollars and up, but generally, it's a democratic medium for collectors.

Lawrence: Do you know how Mark would answer that question? How does he discern his collection?

Erik: I wouldn't put words in his mouth, but he's pretty omnivorous, which doesn't mean he likes everything. As a former art history person who taught sculpture and was an artist himself, he has excellent taste—he's quite accurate in distinguishing excellence from mere fun. But because it's a completist operation, he takes in a lot of material, though I don't think he has every silly Rick and Morty blotter out there.

Unlike street blotter, which mostly doesn't refer to LSD directly—maybe through wink-wink symbolism like lightning bolts or occasional Albert Hofmann references—vanity blotter often reflects on and remembers LSD history. For example, there's a wonderful portrait in the book of Orange Sunshine chemist Nick Sand in protective gear, looking in a mirror. It's clever and captures his personality well.

There are other examples, like Ryan Kerrigan's blotter commemorating Dock Ellis's no-hitter against the Padres in 1970—a key moment of black psychedelia. Because of its outsider status, blotter can serve as a memory palace for underground history, sometimes in nostalgic ways like Dancing Bears or Ken Kesey images, but also in more complex and interesting ways.

Lawrence: Could you explain why the paper was criminalized because of its association and as the medium?

Erik: That's an interesting question because it was somewhat ambiguous. Paraphernalia has a particular legal status, like crack pipes or syringes—things that can have other uses but are part of drug taking. They have a gray market quality that is not explicitly scheduled or controlled yet potentially illegal due to their intimate connection.

The most interesting story involves Mark McCloud, who collected and then started making blotter for trade before being arrested with a huge amount of undipped material. They surveilled him for months, took everything from his house—all his archives and materials—and mounted a serious case against him as a supposed kingpin. But all the paper from that bust was undipped.

In court, they showed some of his paper, which were found dipped from dealers across the country. Mark's lawyer argued this only proved someone bought his paper and dipped it—they couldn't pin it on him. The question became: why would he have all this paper? The defense hinged on the idea that blotter by itself is art. This classification as an art object was instrumental in keeping Mark McCloud out of prison.

This also kick-started the whole vanity blotter world we discussed earlier. Others realized there was case law supporting undipped blotter as legal. In the early years, people buying undipped blotter art were advised to frame it, as the police might still make arrests due to its ambiguous status.

Of course, you can still use it. If someone's too lazy to make their own paper, they might buy vanity blotter and dip it. Some vanity blotter isn't printed well enough to dip, but the higher quality material—more valuable because of the care taken in production—is excellent for putting drugs on.

It gets appropriately loopy in terms of its status—whether it's illegal or not, whether there's something untoward about it. That ambiguity is part of what makes it interesting.

Check out everything Erik Davis is up to on his long-running blog, Techgnosis, and his email newsletter, Burning Shore. Purchase Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium and other books by Erik Davis from MIT Press, Bookshop, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Powell’s.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments