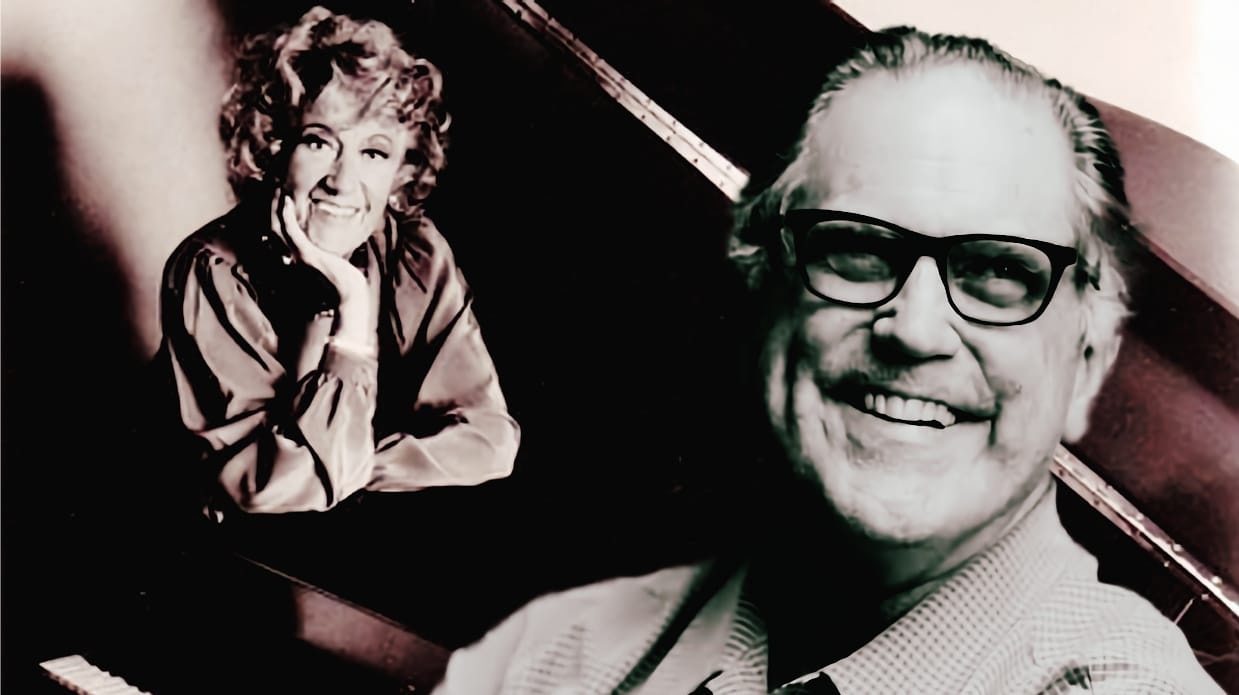

For jazz critic Paul de Barros, chronicling pianist Marian McPartland's life meant navigating layers of carefully curated personas to find the truth beneath. His biography, Shall We Play That One Together? (reissued by the University of South Carolina Press with an informative new foreword by the author), reveals McPartland as both the familiar host who guided millions through the culture and complexities of jazz on NPR's Piano Jazz and an artist who spent decades finding her authentic musical voice.

McPartland's journey from proper English pianist to American jazz innovator traces an arc through the history of twentieth-century music. She emerged from the variety halls of World War II-era Britain to become an essential figure in American jazz, though not without difficulties. The path required her to grow beyond the comfortable confines of mere entertainment and risk revealing her genuine artistic self—a process that paralleled the larger evolution of jazz from popular dance music to a serious art form. Through de Barros's careful research and intimate access, it's apparent how this rich and varied life led to the beloved and influential figure that McPartland became.

Beyond her own musical development, McPartland has an extraordinary legacy as a cultural bridge builder. The archives of her Piano Jazz radio show are an unprecedented archive of musical conversation, capturing giants like Bill Evans and Dizzy Gillespie in candid moments discussing their craft. McPartland also championed women instrumentalists decades before gender equity became a mainstream concern in jazz. Most crucially, she helped demystify jazz for general audiences without diminishing its artistry, bringing sophisticated musical concepts into millions of homes through the power of her engaging personality and genuine curiosity about her fellow artists.

Lawrence Peryer recently hosted Paul de Barros on the Spotlight On podcast for a wide-ranging conversation about Marian McPartland's life, legacy, and the many challenges of getting the full story from such a fascinating but guarded jazz luminary. De Barros also gives valuable insight into the art of the interview, implying its similarity to jazz improvisation—a delicate dance between structure and spontaneity, between faithful reproduction and creative interpretation. The transcribed interview has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On podcast player below.

Reading the Room

Lawrence Peryer: You've interviewed many people in different degrees of depth over the years. How do you handle any psychic resistance you know you're running into, such as when you're getting canned answers? As a craftsman, how do you chip away at that?

Paul de Barros: It's like being in a boxing match. You're just like, "Are they leading with their left? Their right? When do they duck? When do they not duck?" Some people are easy. Other people are guarded. Other people are just plain liars. You have to just read the room.

There are two or three really important things that all of us who have been in this field would agree on. The first one is to do your homework. There's nothing more frustrating for an artist than to have some ignoramus sitting there asking idiotic, inane questions that they could have asked their cat. As an interviewee with a student newspaper, I just had that happen to me. At the end, I said, "Can I just tell you a couple of things with all the greatest love in the world? Don't ever interview an author without reading their book."

Lawrence: Jazz or non-mainstream music artists are grateful when you've done your homework, right? There's not a lot of coverage these days. We get a lot of feedback like, "Thank you so much for actually listening to the music."

Paul: And so many people don't. So, know the stuff. But then, beyond that, I have a rule of thumb: always ask your hippest question first. And what I mean by hip is to show that not only have you listened to all the records everybody knows about, but you've also listened to that record nobody knows about. You say, "Man, how did you wind up doing that record with Bob James in Philadelphia in '71?" The person at the other end of the line or across the table from you will think, "Oh, this person knows who I am." Because that's what we want; we want to be seen.

Sometimes it doesn't work. And again, you just have to be aware, just like if you were playing music. I interviewed Ray Charles for the Jackson Street After Hours book, my jazz history of Seattle. Ray Charles was notoriously unpleasant despite his public image and could be mean. Ray didn't have any time for anybody he didn't trust, and he didn't trust most people for obvious reasons. The way Ray grew up and that he was blind—people tried to cheat him all his life, which made him a very mistrustful person.

Ray had a very tight iron circle around him. The only way I could finally get in to interview him in his studio was to have Quincy Jones call him personally and say, "Ray, you have to do this. Paul's okay." It wasn't enough that I could call the manager and say, "Quincy says it's cool." He said, "No, we need to hear from Quincy." It was just ways of making sure it wasn't going to happen, you know, but it finally did.

So I get into Ray's studio. There are all these keyboards, and he is drinking tea. He just is not putting out a friendly vibe. I know he's thinking, "How long do I have to put up with this guy?" I ask him what I think is the hippest question about the Seattle scene, which is about this bass player named Milt Jarrod. I knew that Milt was important to him in his life, and this was nothing. After twenty minutes, I thought, "Wow, I'm not getting anything."

So, if I'm getting frustrated and worried, I look around the studio and see a Rhodes piano. Out of the blue, I said, "Ray, how do you like the Rhodes, man? I know you started with the Wurlitzer, and nobody else was playing that, and then everybody turned to the Rhodes." And suddenly, if Ray Charles could see, you would see his eyes light up. He looked at me and said, "You recognize that's a Rhodes over there in the corner?" I said, "Yeah." "Well, what else do you want to know?" [laughter]

Lawrence: I have found that in these situations, as well as working with artists in their art or professional lives, most are essentially music nerds like us.

Paul: There's a kindred spirit. And I think Marian came to feel that way. She, like Ray Charles, was not a trusting person. I don't know why. I never found anything in her background, other than her bad relationship with her mother, to make her feel like everybody was trying to trick her, dupe her, or get something out of her. But that's the way she acted. It was really hard to gain her trust.

A Common Denominator

Lawrence: I'm curious about your interest in Marian McPartland as a subject. What were your feelings about her standing or place in the tradition when you first decided to take on the project?

Paul: When I came to Marian, I thought of her as an interesting piano player, but what attracted me to her was her jazz advocacy. I was intrigued by the fact that this woman from England, with this amazing voice on the radio, was so fluent in playing the music and the personalities and culture. Unlike many people who loved the music, she could get across to the average person. Marian was someone where if you're at a cocktail party and you said you're into jazz, inevitably the first thing out of somebody's mouth would be either, "Yeah, I love Dave Brubeck" or "I listen to Marian McPartland." She's a common denominator. That intrigued me.

Lawrence: In the new foreword to the book, you discuss the specific challenges of working with Marian and, more broadly, the tension, constraints, and opportunities that having direct access creates.

Paul: It was intimate; that's the best word for it. It was like a biographer's dream. Biographers go to libraries and sift through people's archives, looking for every scrap of information. Marian was her own archivist. Down in her den, below the kitchen in her lovely little house in Port Washington on Long Island, she had the Marian McPartland and Jimmy McPartland archive and library. You've got all the articles, and then you're reading something that makes you think of a question like, "When did you meet Django Reinhardt?" And all you have to do is walk up the stairs, and there she is in the kitchen having tea, and you can ask her directly.

On the other hand, she was a very guarded person, so despite that physical intimacy for four or five months at her house, six days a week, she also had a ready-made answer for every question, and it wasn't always true or complete. That was one reason she had so much trouble letting somebody else write the story.

Lawrence: Yeah, I don't remember the exact number, but you weren't the first and maybe not even the second to try, right?

Paul: The sixth! She initially had that reticence—she wanted me to stop talking to people because she said, "You've got the story. The story's about me." Marian told this story about when she first heard Helen Merrill, the great singer. She and Jimmy were driving, and they just pulled off the highway to listen to the rest of the song. But Helen kept telling Marian, "Just tell this guy the story. Why are you making up all this stuff? He wants to know the truth. He's not going to do anything wrong."

Lawrence: It's interesting that even dissuading you from calling people, that hook of control...

Paul: She was just trying to put people in their place all the time. It wasn't because she was a jerk—that was how it manifested, but it was just out of fear. Marian was always scared that she wouldn't make enough money, that she wouldn't make ends meet, and that her career wasn't going anywhere. She overcompensated so much that she made a really good living as a jazz musician, which says a lot. Marian was a very hard worker and ingenious at coming up with ideas for keeping her career going and fresh musically.

Learning to Swing

Lawrence: Something I liked early on in the book is the span of time that her life and career encompassed. Could you talk about the musical stew she came out of?

Paul: She came out of a completely different tradition of being a variety entertainer. It did her a disservice for many years because she was so good at it that she leaned on audience-pleasing things for many years in her music. None of that was ever going to get her anywhere artistically.

She was such a really good listener—she had a great ear. And she was a good mimic. I think it helped her in those years when she could come in for a rehearsal in the morning for a show that would be that night and have the book down.

What makes you a great jazz player is reaching into yourself and finding what's inside, putting it into music, and swinging. Musically, England was way behind the jazz curve because the BBC didn't like jazz. So, they didn't get music like Benny Goodman, Jimmy Lunceford, and Count Basie. It just wasn't played.

Lawrence: They mostly played easy listening or what we would think of as easy listening.

Paul: Yeah, it was warmed-over jazz but had a racial bias. It was really like the Paul Whiteman bias of "let's make this Black music not sound so African. Let's get this rhythmic business out of there and make it a little more sweet." And that's what she grew up listening to: bouncy-feeling music. It wasn't swinging.

We talked pretty deeply about this because when you come up as a white person in America and you're enamored of Black music, there are places to go to get it. I grew up as a tenor saxophone player, wanting to sound like King Curtis. Well, that wasn't an impossibility in 1961. You had the records, and you had Black guys playing the music that you could see. She didn't have any of that. She was a white woman, a girl in England. Prim and proper middle class. How was she going to figure this out? So she slowly learned to swing from Jimmy McPartland, Bill Crow, and Joe Morello.

Lawrence: In reading the book, almost as soon as you introduce Jimmy, there's the foreshadowing that this will never work. Yet they were connected forever. They were so different temperamentally and in how they approached life. It seems they were designed to make each other crazy, or he was certainly designed to make her crazy.

Paul: And yet they did have a lot in common. They were both rebellious. They did not want to be bossed around by anybody. They had this jazz attitude of saying, "I'm going to do things my way." They were both very compassionate people who wanted the world to be nicer. And they liked the role that music played in that. So they shared many basic jazz music values, even though he came from this ruffian background in Chicago, and she went from this kind of bland middle-class background in Bromley.

When I talked to Clint Eastwood about Marian at the Monterey Film Festival, I said, "What about a film about Marian?" He said, "I would do a film about Jimmy and Marian." He was fascinated by Jimmy, who he heard in Oakland growing up.

An Epic Life

Lawrence: How you described her music and her musical evolution sounds emblematic of somebody who could or would give a little but not give it all. It took a while for her to be able to be vulnerable musically.

Paul: I think that's very perceptive. Like many artists who never even crossed that threshold, it was difficult for her to realize that the place where you reveal yourself the most is the place where you're usually most scared to go. Because you lose control or you think it's stupid.

Let's go back to Ray Charles for a minute. At least three people told me that in Seattle, Ray Charles used to sing the way that made him famous as a joke. He thought it was funny to sing the blues in the style of gospel music. He thought it was just cute. It turned out to be the invention of soul music.

Sometimes, the things we think are trivial to our creativity are the best things we have to offer. And I think that Marian didn't know that, and it took her a while. I asked her, "Why did you play that way with Linc Milliman on this record? It's like you're somebody else." And she said, "I don't know, I just decided it was time to let it all hang out." That was in the sixties when your friends would suddenly say, "I'm going to India. I quit my job." People made crazy decisions to be free, and I think that helped her.

Lawrence: How you frame the before and after for her in the sixties shows that she came into the seventies differently.

Paul: She did. Marian knew what she wanted to play and was fed up with trying to please everybody else to make money. She figured, "Well, I'll make money in the schools. But I will make music I like when I make records instead of trying to do this garbage I've been making for Capital Records." I don't think she thought the Capital stuff was garbage, but there was that horrible record, My Old Flame, and I found some things she didn't tell me about. She actually did a record for Muzak. She didn't want anybody to know about that stuff. I can't blame her.

Lawrence: What's Marian's relevancy to what's going on in today's jazz? Do you talk to contemporary artists who know her and look back to her?

Paul: I do, and I think that her influence is huge amongst a certain cohort of women, including people like Joanne Brackeen and Maria Schneider, who would readily tell you that Marian was inspirational in how she stood up constantly for women musicians. She helped just by saying, "Why aren't you listening to this person? All these women players can really, really play."

There's a dedicated cohort of musicians that picked up the flame—people like Terri Lyne Carrington and the trumpet player from BC, Ingrid Jensen. They're stepping forward and pulling some political levers that Marian never could. Instead of saying, "We're going to have a women's jazz festival," they go to the main jazz festivals and say, "We're playing here. How many of us are you going to hire now?" And that's what's happened in the last ten years.

I can't say Marian is responsible for that, but there's a direct line between what she did and said all those years, and I don't think any of the women involved in that movement today would deny it or suggest that there's no straight line between them.

Lawrence: How do you view her NPR show Piano Jazz? As someone who does a lot of research work, how do you value that body of episodes?

Paul: I think the Piano Jazz Archive is a huge resource. Shari Hutchinson, Marian's producer for almost the entire show, and I have talked about trying to turn it into an accessible archive, a jazz education resource.

I think it's an incredible document. You've got Teddy Wilson, Cecil Taylor, and the early Diana Krall and Norah Jones. You've got Dave McKenna. You've got all these piano and horn players, Dizzy Gillespie, and the Bill Evans tape. Not only is the playing there, but you have Marian, who's knowledgeable, asking questions and drawing out answers and analyses in many cases.

The Dizzy Gillespie one is one of my favorites, where Dizzy recognizes that Marian isn't hearing bebop the way he hears bebop. And so he beats out the counter rhythms for her. It's like, "No, Marian, this is how it is," and talks to her very sophisticatedly about six chords and how they can work differently than she's thought. Where are you going to get information like that?

Lawrence: That's incredible. And accessible to the public.

Paul: She had to learn to do that. Shari told me that the first time she had Bill Evans in the studio, she started referring to musicians without explaining who they were, as if everybody knew. Shari had to take her aside and say, "Marian, most people listening to this show don't know who that person is. You need to say bass player from the forties."

It was a rare privilege to get to know Marian McPartland, a creative and intelligent woman who had lived an epic life. Not many people get that opportunity, and I'm very grateful.

Lawrence: If you could have a shot at one more person to have that level of intimacy with, or with their material, who would it be?

Paul: Well, this may shock you, but once I finished that book, I vowed never to write another biography again. (laughter)

Lawrence: Fair enough.

Paul: It was frankly just too much emotional turmoil. At some points, it wasn't fun to be deeply involved with somebody else's life. It gets a little confusing. But it was sure a great experience. I've been asked about other people, specifically asked to do various biographies. And I just said, you know what? I think I'm done with biography. If I work on another book, it'll be a novel or a book of short stories. (laughter)

Purchase Shall We Play That One Together? The Life and Art of Jazz Piano Legend Marian McPartland from USC Press, Bookshop, Powell's, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments