Laura Nyro had a bad night at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967.

‘The evening hit bottom with Laura Nyro,’ music writer Michael Lydon wrote in his account of the festival. He described her as a ‘disaster…who [could] be written off from the start…a melodramatic singer accompanied by two dancing girls who pranced absurdly.’ Nyro certainly felt the same. Reportedly convinced that the audience was either jeering at her or preparing to, she left the stage in tears. The night belonged to Otis Redding, Jimi Hendrix, the Who; certainly not to a weird nineteen-year-old girl dressed all in black and singing old-timey-sounding songs like ‘Wedding Bell Blues’, which offered a disorientating combination of Broadway showmanship, jazz rhythms, and Motown-style backing vocals. The set was at best disappointing and at worst a complete debacle that told Nyro she shouldn’t bother with live performance again. She was just too weird, even for Monterey, a concert where psychedelic music took front and centre. For a moment, it seemed that she would fade away from popular music just as quickly as she had flickered into it. But six years later, Nyro was not gone; far from it. Columbia, her record label, had even gone ahead and re-released her debut album, newly titled The First Songs, which celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this year.

What happened in those six years? For starters, Nyro was staggeringly prolific, putting out four albums in four years: Eli and the Thirteenth Confession(1968), New York Tendaberry (1969), Christmas and the Beads of Sweat(1970), and Gonna Take a Miracle (1971). But these releases only tell half the story; none of them even saw much commercial success (though they were critically lauded). What really happened between Monterey and the First Songs re-release was that other recording artists took Nyro’s songs and made them hits. Some of these songs came from Nyro’s later albums (‘Eli’s Comin’’ off of Eli and the Thirteenth Confession, was a hit for Three Dog Night in 1969), but many of them came from that initial record. Originally released by Verve Folkways in 1967 as More than a New Discovery, it has more hits on it than any of Nyro’s other albums.

Those hits — ‘And When I Die’; ‘Stoney End’; ‘Wedding Bell Blues’ — came to be crucial entries in the pop canon of the late sixties and early seventies. And, remarkably, each of them sounds like it could have been penned by a different writer. Barbra Streisand’s screamingly melodramatic rendition of ‘Stoney End’, for example, is worlds away from the plodding Western-style recording of ‘And When I Die’ by Blood, Sweat & Tears. Both are in a different ballpark to the Fifth Dimension’s version of ‘Wedding Bell Blues’, which has the same light, airy quality of whipped cream. Only on The First Songs, in Nyro’s voice, do these pieces come close to occupying the same universe.

There’s a strong argument for the irrelevance of re-releasing any album. This one in particular, because Columbia’s release of The First Songs was not even the first re-release of Nyro’s album — Verve Forecast was the first to repackage More than a New Discovery as The First Songs in 1969, two years after its initial release. In many ways, Columbia’s version was simply a money-grabbing exercise. They wanted a version of the album on their label, since the others existed on Verve. They also wanted to fill a void that Nyro had left. Two years earlier, in 1971, she had gotten married to a carpenter, moved to the countryside, and decided to retire from music at the tender age of twenty-four.

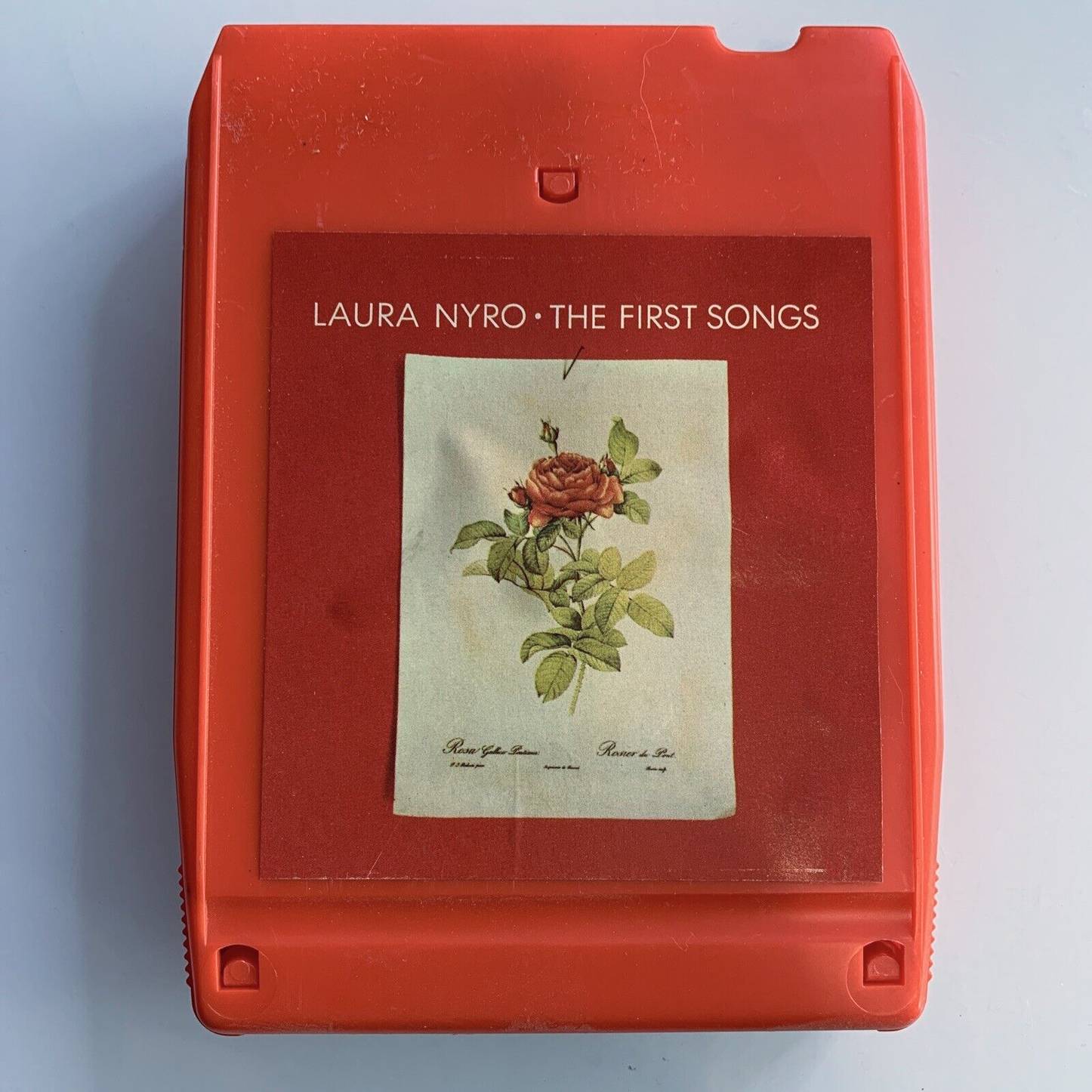

But the re-release also reflects the remarkable impact that Nyro had made on popular music in a relatively short amount of time, and the track list of The First Songs reflects this. For one thing, it’s reordered to prioritise the hits. ‘Wedding Bell Blues’ opens Side One and ‘Flim Flam Man’, a hit for Streisand in 1971, opens Side Two. The album closer is ‘And When I Die’. For another, Columbia chose to rebrand the album entirely, with a new illustration of a rose against a yellow and red background. The removal of the original album art — a darkly framed photograph of Nyro looking down with a smile at something just off-camera — feels like a loss, the destruction of something. And much like the new title, it aims to rebrand Nyro as a songwriter, not a singer.

But it only takes ten seconds of The First Songs to recognise that Nyro was a singer. And what a singer! A range three octaves tall and wide, with a hearty belt and almost overwrought diction; Nyro wails and growls and catapults, holding up against brass backings, unimpeded by rhythmic variations and key changes. It isn’t even effortless. It’s full to the brim with effort. That’s the point. Even as early as The First Songs, everything is gut-wrenching with Nyro, whether she’s desperate to get married or telling the men of California what to do (‘You can shine m—eyyyyyye shoes!’ she informs them on ‘California Shoeshine Boys’, chewing through the vowel sounds like a cowgirl chewing tobacco.) But even on her most aurally upbeat numbers, there is in her voice a keenly felt and unambiguous pain. It provides the thumping heartbeat of songs like ‘Stoney End’, which is written with pure naïvety of C Major and, in Nyro’s recording, opens with the cheery wheezing of a harmonica, but in actuality details an aching story of poverty and grief.

The question of what a singer-songwriter is started about the time Laura Nyro was making music. Nyro came of age with a slate of musicians who made it big not just because they could sing (sometimes they couldn’t sing) but because they could write. By the 1970s it was no longer enough to be a good singer: to be notable, a true musician, you had to write your own songs too. This is an unspoken belief that is an undercurrent of how we scrutinise pop music today. Even though some of our biggest pop stars are singing songs written by another person (take Max Martin, who has handed out so many hits he strung together a West-end musical from them), it’s just cooler if they had a hand in it too, or at least if they say they did. But the thing is that singing is an act just as alchemical, as mystical, as sophisticated as songwriting. That’s what makes The First Songs so special. ‘I have to sing,’ Nyro said to Ed Sciacky in a rare interview in 1989. ‘I see singing as an art,’ she told him, with an air of confession. I wonder why it seems unpopular to admit this today. Pop singers have developed an art to their craft, too, just as opera singers do. When, in the same interview, Sciacky asks Nyro if it bothered her that she wasn’t heard singing her own music as often as other people were, she pauses. ‘It’s kind of a nice thing for a writer,’ she says diplomatically. But what about the singer?! you can practically hear Sciacky wanting to say. Isn’t the singer just as important?

When I think of Nyro’s response to Sciacky, I think what she was really trying to do was not ignore the role of the singer, or even lower it in comparison to the role of the songwriter, as we so often do. The fashion of the singer-songwriter reflects a modern fascination with autobiography and voice, and this is particularly true for women in the music industry. It feels impossible nowadays to separate a singer from the songs, even if they’ve made every effort to write distinctly from another perspective. If Nyro put out ‘Wedding Bell Blues’ today, it’s all too easy to imagine the discussion that it might prompt: who is Bill? How long has she been seeing him? Is there a statement here about women and marriage? Is she actually going to get married soon? Never mind that Nyro wrote Wedding Bell Blues when she was fourteen and it isn’t even about her. It’s not only more convenient to elide singer, songwriter and person. It makes more money. Nyro sensed this, and it’s part of why she disliked the industry and its trappings so much. Sciacky’s question pays deserved attention to the role of the singer, yes, but it also subconsciously betrays how we see voice as immediate autobiography, how anything that a person sings aloud should somehow be a part of them. Nyro’s stance is one of equal weight, and audible across every track in The First Songs. Yes, songwriting is an art; and so is singing. They are not inextricable. Rather, we gain more from each when we understand them as acts that complement each other, not ones that are co-dependent.

On the first episode of his show Spectacle, Elvis Costello and Elton John watch a clip of Nyro singing ‘Wedding Bell Blues’ at the Monterey festival, the very same one she apparently bombed. ’If she came up there today with that look and that sound, I think she’d take it right into the charts,’ Costello comments. But I don’t know if that’s true. Even on a commercial repackaging like The First Songs, Nyro is weird and complex; she messes around with rhythm, writes confusingly obscure lyrics (‘the lyrics still confuse me today,’ Barbra Streisand said of ‘Stoney End’ in 2014), crunches together harmonies that are delicious, yes, but also disorientating. If fifty years of The First Songsproves anything, it’s that Nyro is still what she always was: a maverick and one who relished not just breaking convention, but pretending it never existed in the first place.

Comments