There's a video of Josh Johnson performing "Marvis," a song from his album Unusual Object. Initially, we see him from above, in the center of a circle surrounded by blackness, and he's flanked by an array of effects pedals and electronic gear. A single note blown into the saxophone becomes a gentle, shimmering drone. Johnson adjusts the pedal knobs with toes adorned in striped socks and adds harmonies and altered layers to a developing sax melody. A steady kick drum appears and somehow swings. The conventional cohabitates with the left field—this is the solo work of Josh Johnson.

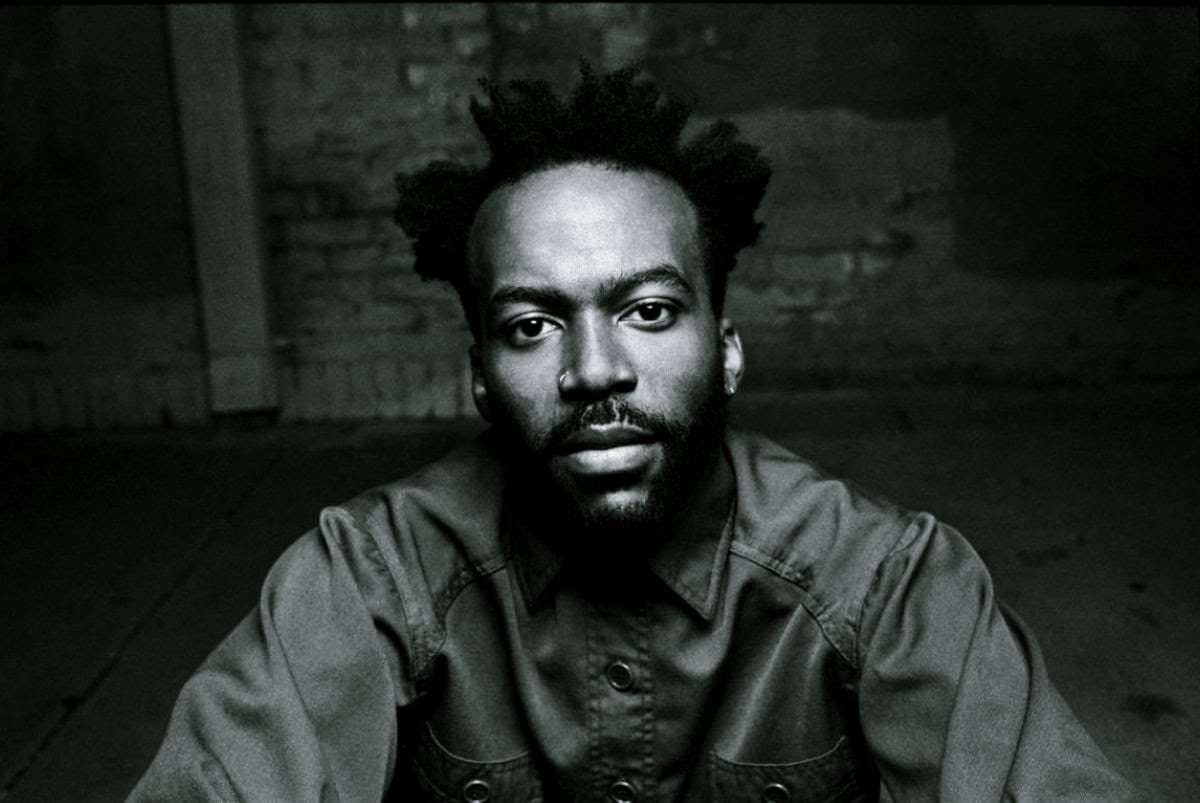

You may have encountered Josh Johnson as a collaborator rather than a solo artist. It's possible you may not have realized this. As a part of the burgeoning and youngster-led Los Angeles underground jazz scene, Johnson is an active member of Jeff Parker's The New Breed and Miguel Atwood-Ferguson's ensemble, has acted as the musical director for singer-songwriter Leon Bridges, and played on songs by a range of artists that includes Carlos Niño, Harry Styles, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Moonchild, and Miley Cyrus. In the midst of all this, Johnson produced Meshell Ndegeocello's The Omnichord Real Book for Blue Note Records. The album went on to win the first Grammy Award for Best Alternative Jazz Album.

Alternative jazz? That's a curious term, probably best interpreted outside of 'alternative' as it applies to rock music or even when perceived as a difference to tradition. But, in a way, we can feel Josh Johnson existing in something that's an alternative to what one might normally expect. There are heaps of tradition homaged in Johnson's work, but they are radically accented with techniques and processes that would stymie the purist set. Unusual Object resolutely expresses this sort of 'alternative' and showcases Johnson's eclectic bent. The album is undeniably jazz, but it's somewhat undefined, too. One can hear with certainty that this is a solo work, but the means that make it 'solo' only appeared in recent history. Johnson explains this better through the "Marvis" video than anyone can.

Josh Johnson recently guested on the Spotlight On podcast, chatting with host Lawrence Peryer about this application of genre, the dual importance Chicago and Los Angeles bring to his artistry, limitation as a tool for accessing creativity, and how Unusual Object began as a solo album that wasn't. Johnson is a deeply creative soul, and we think you'll enjoy this conversation, which has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Who Benefits From Genre?

Lawrence Peryer: Something interesting about your Grammy win is this idea of 'alternative jazz.' I'm a Grammy voter, so when I open the ballot, I have to pick categories, and I make a beeline to the jazz section. Seeing how things get filed, sub-filed, and classified is always interesting.

Josh Johnson: I have a lot of different feelings about it. I'm often asking myself, who benefits from genre? What are we hoping that genre does?

To me, 'alternative jazz'—the naming of that category—is somewhat of an acknowledgment that we understand that our labels are insufficient. We don't know how to get too specific, but here's another avenue for music to be recognized within this institution. It's positive that there's an acknowledgment that we've been trying to fit so much under this umbrella, and maybe it's not representative of how music is being made.

Lawrence: The Grammy you won was for Best Alternative Jazz for an album you produced for Meshell Ndegeocello — The Omnichord Real Book. You could say, "Yeah, I guess that's alternative jazz" because there's going to be a shorthand that develops, and, you know, it's not a Count Basie reissue. So, I guess it's alternative jazz.

I hope that classification is almost like an incubator. In a few years, it will be like, "This is the new mainstream or where the genre's moved forward." It doesn't matter for the music, but those things have a way of sticking over time. If it encourages someone to make music, I'm into that.

Josh: We're naming things after they happen. I think that spirit and the music are being made. I guess the question is, does a category like that bring some wider stuff happening in communities around the world?

Lawrence: Given the diversity of work you've done, different players, different contexts, and different roles within the project, have you noticed any career impact? Does the phone ring differently because of the Grammy?

Josh: There's an impact that may be less connected to career—someone being like, "Hey, I saw you won a Grammy. Now, I want you to be a part of something." Perhaps it's helped connect me with other people in communities I sometimes step into. I feel like I kind of move between a lot of different worlds.

Lawrence: If something you're doing in one area can bring some love and light to those other areas, that's not a bad thing at all.

Josh: Meshell Ndegeocello embodies that very much. If 'alternative jazz' is the name we need to give to the thing that can recognize and alchemize a unique presence in music, then I'm cool with that.

Navigating the Unknown

Lawrence: Do you know what someone thinks when they need to call Josh Johnson? How might that be different when it's a music director role versus a "come in and help me produce a project" role versus "come in and do that crazy thing you do with the saxophone"? Do you know what it is?

Josh: I'm not sure that I do. Sometimes, it's more general—we need a person who does this. We think this person would be a good fit. Increasingly, it's much more specific. It's not just like, "Oh, the song needs a saxophone." It's situations where I'm asked to show up with my perspective on music and its influence on how I make music with others.

To your point, it is different in different situations. And it can be hard for me to know. I'm finding that there are times when people articulate clearly what they're looking for. There are other times when that's something we'll discover as the music happens. I think I'm learning to walk into the room, curious and ready to learn something. That's been a good way for me to navigate the unknown.

Lawrence: The word "curious" is a proxy for a certain open-heartedness and open-mindedness, like bringing a vulnerability to the table that allows you to be tuned in sensitively as an artist.

Josh: That's important to me. I think something I've come to understand as an important part of my life and my life in music is leaning into that and seeing that as something that is—I don't want to say valuable in the capitalist sense—but can be energizing for other people.

Lawrence: Can you tell me about the music you were first exposed to? And what was the first music you chose to listen to as opposed to the ambient sounds of your parents?

Josh: My parents are big music fans. So I think the first music is probably like a mix of soul, gospel, and R&B playing around the house, soundtracking early childhood. When you're a kid, your access to music is through what you hear around you. And there comes a point where you become or have the means to seek things for yourself. But I would say it was kind of like R&B and hip-hop. It was mixed with electronic music, indie, and post-rock stuff by middle and high school.

I was also playing music in church, in a way, but jazz still came into the picture early. That's when I first started playing saxophone, fifth-grade band, or something like that. I remember taking to it and asking for some CDs of saxophone players for Christmas. And I think my parents got me like a stack; maybe it was like five things, and four of them didn't connect with me. The one that did was a Lester Young compilation. I put it on, and I was like, "This dude's talking to me."

Roots in Chicago

Lawrence: I love talking to artists from the Midwest in general, but Chicago in particular, just because of the sort of melting pot slash lineage for American music. As you grow as an artist and a human being, do you have an articulation of the importance of Chicago to you as an artist?

Josh: It's interesting to have been away from there for so long—Los Angeles is my home now. I would say that Chicago is integral to the foundations of my music-making experience as a player, but even more as a listener. That was where I experienced culture, and I think it was also such a fertile artistic community with a lot of infrastructure.

Even with firm roots in Los Angeles, there are so many things in my life or people I'm connected to and make music with that have roots in Chicago.

Lawrence: What was the initial reason for choosing Los Angeles over staying in Chicago?

Josh: So I'd attended Indiana University's Jacobs School of Music and then moved to Chicago. Then, a few friends applying for a fellowship program encouraged me to apply. It offered direct mentorship from some musical heroes of mine. Ultimately. I got invited to audition for this program, which meant coming out to California for the first time. I ended up getting into that program.

Many different kinds of teachers came in and out of there, but the biggest draws were Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock. I thought I would do that and then return to Chicago or move to New York. But once I finished, it felt like I'd started to connect with and find community here. I was excited about some of the things happening here and just being able to explore some other interests in music.

Lawrence: The group of musicians generationally that have emerged in Los Angeles over the last fifteen or twenty years is incredible. I see how the city emerged and the fascinating creative music scene there. There's so much great stuff going on. The way genre is integrated and transcended is exciting.

Josh: It's interesting. I mean, it's changed so much even in the time that I've been here. I remember finishing grad school, deciding to stay, and telling friends in Chicago or New York. And everybody's like, "What are you doing? Why would you do that?" And it's interesting to see some of those people now live in Los Angeles.

Play the Same Way You Hope and Dream

Lawrence: Could you share a Wayne Shorter anecdote? Did he drop any knowledge on you? I view him as almost like a Yoda figure, and he might tell you more about life than technique or harmony.

Josh: He was never really talking about music in musical terms. Wayne Shorter encouraged you to pull things out of yourself that you didn't know existed. There's a lot of mystery to it, for sure. He's often talking about music as it relates to an actor playing a role in a movie.

I remember we took a break from rehearsing, and he was sitting at the piano, just putting his arm down and hitting a bunch of notes. He pointed to me and said, "You got to play the same way you hope and dream."

It's never like, "On this chord, you do this thing," but it elicits something out of you that you're like, "I don't know that I understand this fully, but I'm reaching for something." And often, what you find is something that's beyond speaking in musical terms. He asked, "Do you ever try playing like a little kid? Do you ever play like you don't know how to play?"

It's abstract enough to think, "It's not about the saxophone. We're trying to tap into something deeper than a note or a chord." Being around that presence helps connect me to the 'why,' reflecting on what space I'm creating or trying to connect. You can get so wrapped up in the tools that you lose sight of the 'why.' What is it that you're trying to express? What's your point of view?

Lawrence: Something that fascinates me about the jazz world is the poles of deep conservatory training—intense technique and knowledge—and the other extreme of oral tradition—the musicians sitting with other musicians talking about philosophy and spirituality, learned and shared wisdom. There's so much richness, regardless of which side of the microphone or the instrument you're on. It's a world that just keeps giving.

Were there touchstones at the beginning where you said, "I want to make something that's mine in the vein of X"? Is there any sense of context or lineage here that you could shed light on?

Josh: I would say not for the whole. There wasn't a template. It feels connected to how I think about influence in music sometimes. For some people, there's a record that they're like, "This is the reference point." And I think, based on my experience, within different material, there are things that maybe I'm conversing with and ideas that I'm trying to explore.

I wasn't sure I was making a solo album. And that's the question in Unusual Object: What's a solo album? It's just one input because there's an incredible lineage of solo saxophone albums in more improvised music traditions. So, the short answer is no. [laughter]

There are ideas that I've been fascinated with or developing. I've been employing these in other people's music and more collaborative situations, but what's it like to try to make a whole work from this? Like, can I? What's it like to try to do it for real?

It's almost a reaction to swinging in the other direction, out of curiosity and interest, but also maybe as a way to reorient myself and my priorities in music.

Lawrence: I love the diversity on the record. Some pieces remind me of almost some Synclavier works from the eighties, like your songs "Sterling" and "Lost City of Industry." They have this very modern classical sort of feel to them in my mind.

Josh: I have a lot of different interests in music, and I've learned that things are best when I'm led by curiosity. Some people start at the same place every time, and they can generate many different things. For me, each thing is different. So, there's stuff that starts on the saxophone. There's stuff that starts at the piano. There's stuff that starts with a sampler and a synth or even a voice. A lot of it begins with improvisation.

As I'm doing something else, I might dream up a certain scenario, like a solo with this shape, only playing in one part of the horn, and then contrasting it with this. So I have a little notebook, and there are always these little ideas that I write down as I have these curiosities. I do the same with composing; some just come from playing or improvisation.

Sometimes, I impose some sort of limitation. That allows me to engage with my curiosity and get a different access point to creativity. There are periods where I'm like, "Cool, I'm writing everything at the piano." But I find that hopping around and using many different processes keeps me engaged, and I also think certain instruments lead you to certain things. When I sit down at my piano, I want to play everything in the middle of the piano. That's where it sounds best. But over time, that influences some of the choices I'm making. Hopping over to another instrument will lead to different ideas and decisions.

When I was younger, I had a narrower view of composition. Now, and in much of what I'm exploring on this record, all the tools are available—anything is fair game. I don't think starting on the saxophone or starting from improvisation with electronics and then developing that idea is any less valid or potentially rich. It's a mix of all of that for me. It's like trying to understand, sonically, if these things live together.

Different Doorways to the Same Place

Lawrence: Obviously, the pieces will have a fundamental Joshness. How do you manifest differently through what a piano can do and what a piano is than through a saxophone?

Josh: It's different doorways to the same place. That's fascinating to me because, like on the saxophone, I have many more facilities. Sometimes, that might lead me to write something more dense than it needs to be because I can, versus another instrument where I need to move slowly. And it's different than the tactile feeling of, "Well, this thing feels like this, but I'm not seeing it." I can't visualize moving from one idea to the next in the same way. And I find that's where all the good stuff is for me.

Lawrence: The palettes are so big and limitless. Whether you're a rules-based artist, generative composer, or whatever, playing around with the concept of limitations is helpful.

Josh: It's essential to me. It's also interesting when you get to that point where you're like, "I feel like I've exhausted this thing, so maybe now I need to expand that limitation." Different access points to creativity are the thing, and the instruments matter to an extent, but imagination is the instrument. It's nuanced, but I truly believe that.

Lawrence: Could you talk a little bit about the role of Paul Bryan beyond just the printed credits? It seems like there's a real collaboration going on there.

Josh: I'd love to talk about Paul Bryan. He is a close collaborator and also recorded and produced my previous album. We play in Jeff Parker's band, The New Breed. We've been making music together for probably almost ten years.

One of his big contributions to this record is sonically giving things a sense of place, often in really subtle ways. He's essential to Usual Object's sound and helps frame the compositions sonically. These subtle moves draw your ear and help support the changes in the song's form. There's a way to keep a listener engaged besides the sonic material, and he's a master of that.

Many of the tracks were recorded with a single microphone, with effects and electronics. There are fewer elements, but they can occupy more space and be more detailed. I think Paul is sensitive and attuned to framing those moments and helped keep me from overworking things. He often has the intuition to say, "Hey, this thing—instead of minimizing that, let's blow it up."

Lawrence: Let's draw even more attention to it.

Josh: And I think that's resulted in some really interesting things. It's opened me up in some ways. Instead of being like, "Oh, that's a mistake" or "I didn't mean to do that," and eradicating this thing, it's like, "What's it like to magnify it?"

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments