It’s difficult today to imagine the impact the movie Alien had when it first debuted at midnight, May 25th, 1979, on the opening night of the fourth annual Seattle International Film Festival.

It’s so entrenched in our collective experience that it’s hard to imagine just how freaked out those first audiences were when the “chestburster” made its splattery (and aptly named) debut. Among iconic horror movie moments, the chestburster scene always ranks highly.

And you’d be hard-pressed to find a horror, science fiction, or cinema fan for whom the titular character (known canonically as a “xenomorph”) isn’t well-known.

What is less well-known is Alien's place in film music history, why it still gives listeners the chills today, and the tumultuous story behind its score.

In Space, No One Can Hear You Scream in a Galaxy Far, Far Away

In May of 1977, director Ridley Scott was still riding high on the critical acclaim showered upon his first film, The Duellists. A historical drama, it won the “Best Debut Film” award at the 1977 Cannes Film Festival. Suddenly a hot commodity, Scott had already teed up his next project. Staying in his chosen lane, his next feature would be another historical drama, adapting the 12th Century medieval tale Tristan and Isolde.

But the chance viewing of a sizzling new phenomenon called Star Warspopped that balloon in short order and changed the course of cinema history.

“I never saw or felt audience participation like that, in my life. The theater was shaking … I thought, I can’t possibly do Tristan and Isolde, I have to find something else. By the time the movie was finished, it was so stunning that it made me miserable. That’s the highest compliment I can give it; I was miserable for a week … Then, somebody sent me this script called Alien. I said, wow. I’ll do it.” - Ridley Scott, Cinema Blend

Scott could hardly wait to make a space movie of his own. Alien, not unlike the film that both depressed him and changed the trajectory of Scott’s career, has since become a cultural touchstone.

In Space, No One Can Complain About Retrofuturism

Alien is one of those rare films that has transcended the time in which it was made to become an example of retrofuturism: not only how those in the past imagined the future, but how those in the future perceive the past. The film owes much of this timeless quality to its score… but the score alone wouldn’t have saved it.

Hairstyles come and go (and come again), making those in Alien look surprisingly contemporary. The clothes are suitably nondescript by design, from plain tighty-whities and t-shirts to workmanlike coveralls. The spacesuits remain believable even compared to modern ones.

And while the movie is set in the year 2122 and the tech, such as keyboards and monitors, does look primitive by modern standards, maybe low-tech utility is exactly what you could expect to see on an old, filthy space freighter.

Their ship, the Nostromo, isn’t a yacht – it’s a commercial towing vehicle. It’s built for function, not comfort, and the crew isn’t even supposed to be awake for most of the trip. The interior of the ship is cluttered at best; grimy and dripping with condensation at worst.

Trying too hard to be “futuristic” is the doom of many movies for whom fashion and technology eventually catch up.

On the contrary, the only entertainment showcased onboard the Nostromo is a brief scene featuring “Eine kleine Nachtmusik.” Captain Dallas, played pragmatically by Tom Skerrit, sits alone in the escape shuttle listening to Mozart while awaiting an update on their indisposed crew member, Kane, memorably portrayed by John Hurt.

Using classical music was a bold and forward-thinking choice, avoiding the pitfall of shoehorning a contemporary pop song into a contemplative scene and thus gruesomely dating the movie.

A classic never ages.

When it comes to scores, not all films can make that claim.

In Space, No One Can Hear You Never Go in the Water Again

Having a score rather than a soundtrack was a fairly novel idea in the 1970s. By and large, cheaply produced (and profitable) soundtracks bristling with radio-friendly pop songs had come to dominate film in the decades after World War II.

Can you imagine Sigourney Weaver’s iconic character, Warrant Officer Ellen Ripley, fleeing the alien through that maze of strobe-lit corridors to the thump of a four-on-the-floor disco beat? It could have happened…

But unlike the alternately hilarious and wince-inducing Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk, it turns out an orchestra withstands the test of time quite well compared to contemporary pop music… and the industry was already going through a sea change, so to speak.

In 1975, Jaws made composer John Williams a film score superstar. Having written one of the most famous scores of all time, he rode the wave of the movie that practically invented the summer blockbuster .

Williams won the Academy Award for Best Original Score for Jaws, redefining what a major hit movie sounded like to the extent that his work for that film isstill talked about in scholarly circles to this day. Suddenly, pop soundtracks no longer possessed the gravitas to carry a major film.

And, instead of being reserved for dignified movies that chased little gold statues, Jaws made film scores accessible to the masses… and profitable.

Williams’ win beat out fellow composer Jerry Goldsmith’s score for The Wind and the Lion. Goldsmith did go on to win his own little gold statue the following year for his score for The Omen, after being nominated eight previous times for other films.

And two years after that, he wrote the score for Alien.

In Space, No One Can Hear Your Score

Jerry Goldsmith had already been in the business for 28 years when he got tapped for Alien, with a prolific resume of respected works for TV and film that stood second to none. He’d already scored major sci-fi hits such as Planet of the Apes and Logan’s Run, making him a perfect candidate.

But he wasn’t the first choice.

Director Ridley Scott’s choice was Japanese composer Isao Tomita. With an education in classical composition, Tomita began experimenting with early electronic music. He was renowned for his synthesizer work, with which he created re-imaginings of famed classical compositions such as Gustav Holst’s “The Planets” in 1976.

Tomita began experimenting with “space music,” and in 1978, released The Bermuda Triangle. It’s easy to see how Scott could have imagined such soundscapes supporting his directorial vision… and it gives one pause to think of how Tomita’s classically-inspired synth work might have sounded in the final cut.

Nonetheless, it was out of Scott’s hands. 20th Century Fox President Alan Ladd Jr. insisted that Scott go with a more “traditional” option in Jerry Goldsmith.

“I was sitting in a projection room all by myself and I was absolutely terrified … I kept saying, ‘It’s just a movie, it’s just a movie,’ but it really scared the shit out of me.” - Jerry Goldsmith, Vulture

Already well-known for being experimental and embracing unusual instruments in his work, Goldsmith put on his creative hat and came up with some truly avant-garde ideas.

In addition to a full orchestra, he included a didgeridoo, a conch (used to make the haunting “alien howl” during the main titles), a renaissance-era instrument called a “serpent,” and an Echoplex. Even with traditional instruments, he employed them in an unusual way, such as string musicians striking the bridge of their instruments with their bows.

Layer these things one atop the other, and you have a genuinely alien score.

While Goldsmith was working away, Scott and film editor Terry Rawlings plugged in a temporary score to act as a sort of guidepost for what they envisioned for the finished product. Some of Goldsmith’s own work on 1962’s Freud: The Secret Passion was used, including the main titles, “Charchot’s Show,” and “Desperate Case.” Also used was Howard Hanson’s “Symphony No. 2” for the end credits.

“We tend to get a pretty great temp score … Because you’re able to choose from anything you want, you can stick in all your favorite stuff, either present or past or just made. And it drives [composers] nuts, because they say, ‘Oh damn.’ I always remember my first experience with one of the biggest of all composers early on, and I had this terrific score for him. He went, ‘Goddamn it, I don’t want to hear it! I want to hear the film silent.’” - Ridley Scott on working with Jerry Goldsmith

Goldsmith was known for being candid, and Scott for being strong-willed. Goldsmith hated temp scores and resented having to write music based on someone else’s preconceived notions. He purposefully ignored the temp score, instead drawing on the film itself for inspiration.

“The message I was getting from him was he wanted me to be visual with the music. Well, I can’t be visual with the music; that’s not what I’m supposed to do. Let the director and the cinematographer put the visuals on the screen, let me do the emotional element.” - Jerry Goldsmith, liner notes for “Alien: The Complete Original Score”

Not content with how Goldsmith disregarded the temp score, Scott sent Goldsmith back to the drawing board to re-write no less than five major cues. Scott wanted to get the tone closer to what he had in mind with the temp score… more dissonant, more ambient, more space-horrory.

"I always think of space as being the great unknown, not as terrifying but questioning … there’s an air of romance about it … I thought, ‘Well, let me play [Alien’s] opening very romantically and very lyrically and let the shock come as the story evolves … don’t give it away in the main titles.’ It didn't go over too well. I wrote a new main title, which was the obvious thing, weird and strange, which everybody loved. The original one took me a day to write and the alternate one took me about five minutes." - Jerry Goldsmith

It didn’t stop there.

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Scott purchased the rights to Goldsmith’s score for Freud: The Secret Passion to use the portions he liked for the score in his finished movie. He also kept Hanson’s “Symphony No. 2” for the end credits in the final cut.

To add insult to injury, Scott and Rawlings sliced and diced Goldsmith’s score and used bits and pieces where ever they felt they best belonged… if at all.

Such a la carte butchery of his carefully curated work, intended to complement specific parts of the movie, infuriated Goldsmith.

In Space, No One Can Deny Greatness

With the availability of audio releases of Jerry Goldsmith’s complete score and video releases featuring his score restored to the film, you can judge for yourself if you prefer his vision over Ridley Scott’s.

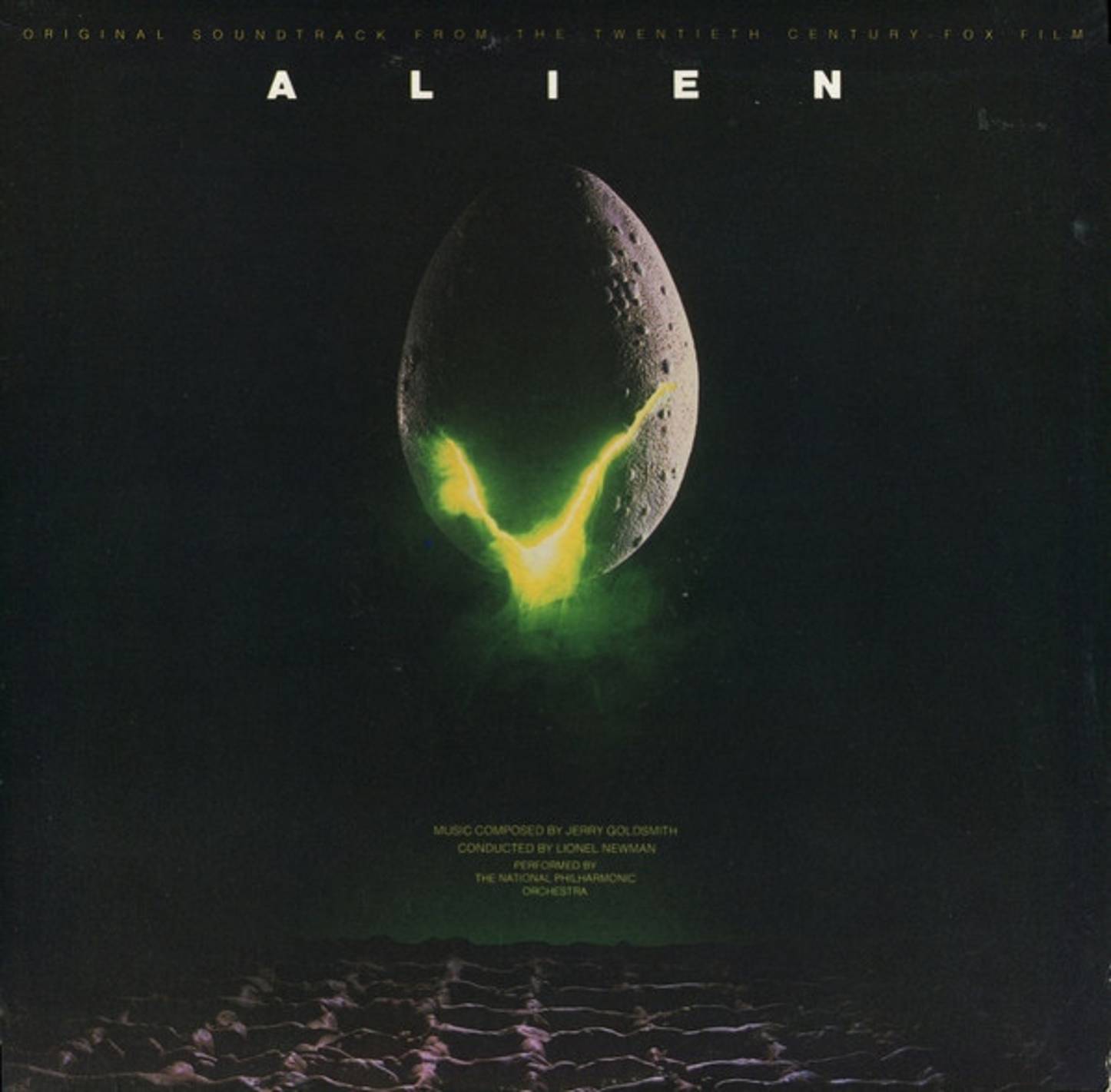

And, whether you agree with Scott’s taste in film music or not, Alien was nominated for 13 awards at the time, including the Grammy Award for Best Soundtrack Album, Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score, and the BAFTA Award for Best Film Music.

That doesn’t include more recent acknowledgments, such as winning the 2007 International Film Music Critics Award for Best New Release, Re-Release or Re-Recording of an Existing Score. This honor was bestowed on Goldsmith’s complete remixed and remastered score using the original tapes, with bonus goodies for the true Alien melophile.

Sadly, Jerry Goldsmith died in 2004, hopefully accepting the honor in spirit, if not in person.

In 1985, he commented, “I told Ridley that working on Alien was one of the most miserable experiences I've ever had in this profession.”

For his part, Ridley Scott later praised the score, saying, “Jerry Goldsmith's score is one of my favourite scores. Seriously threatening and beautiful.”

What a perfect summary of the film as a whole.

Comments