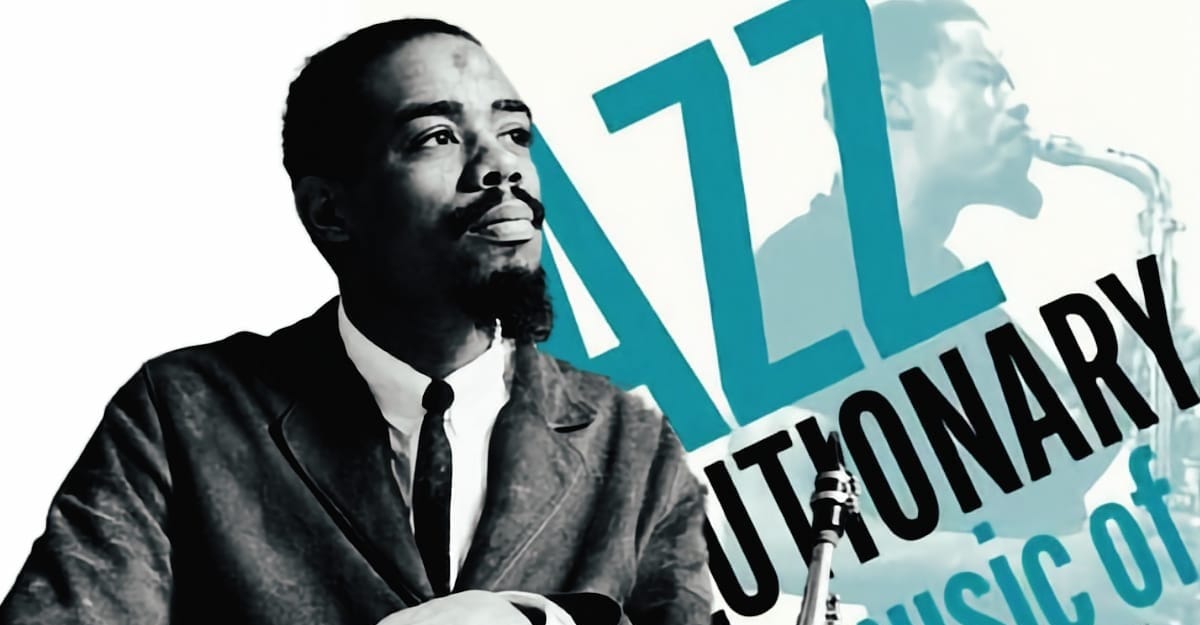

Time moves differently in jazz mythology. Legends stretch across decades while lives end too soon, leaving behind scattered recordings that echo with unrealized possibilities. Eric Dolphy's distinctive voice—through alto saxophone, flute, and bass clarinet—speaks of these tensions between time's persistence and its sudden stops. His sounds float through the air like particles of light caught in an old photograph, simultaneously present and irretrievable.

The segregated streets of 1940s Los Angeles shaped Dolphy's early musical consciousness. Dreams of classical performance crashed against racial barriers while bebop filtered through Central Avenue's nightclub windows. Here began the pattern defining his artistic journey: doors closed while others opened unexpectedly, and each newfound artistic relationship nudged Dolphy toward innovation. The young multi-instrumentalist who once yearned for symphony halls would instead help architect new sonic spaces, pushing against convention until convention itself began to bend.

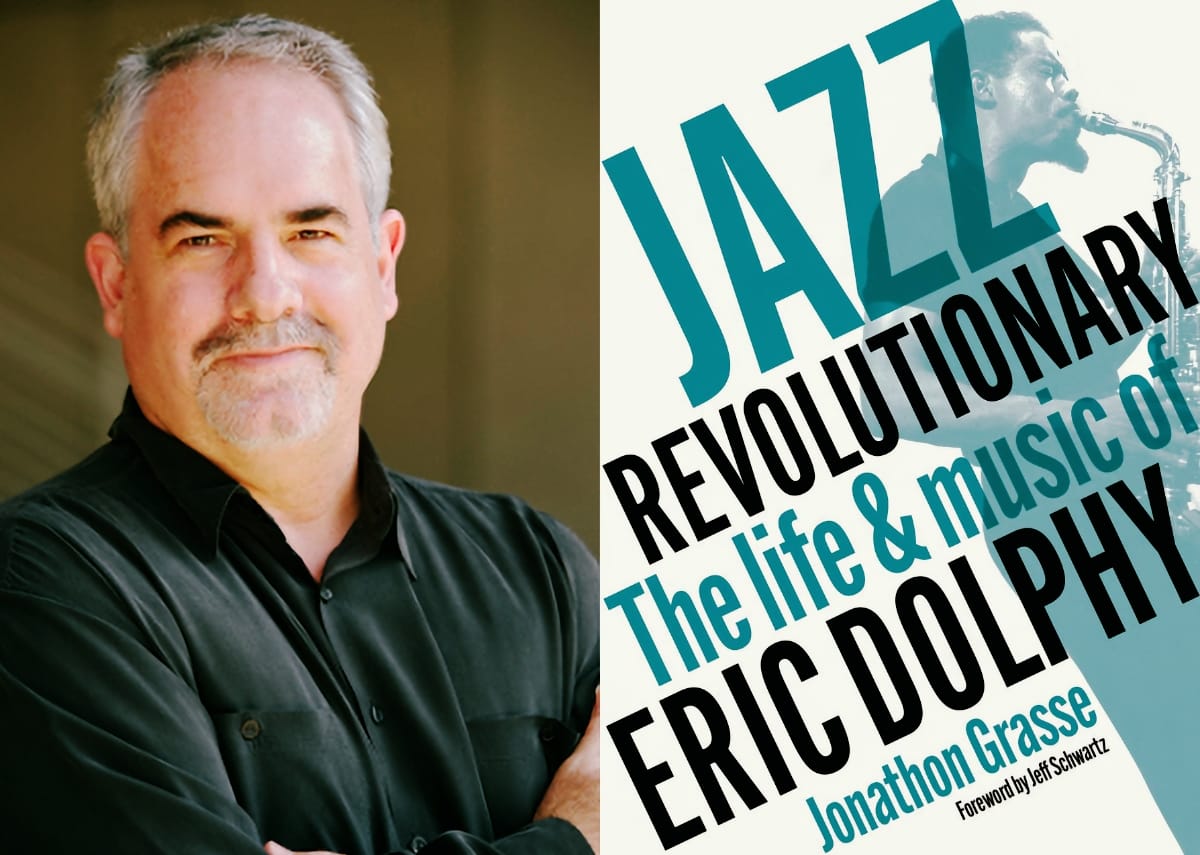

Jonathon Grasse's Jazz Revolutionary: The Life & Music of Eric Dolphy excavates these moments of transformation with scholarly precision and deep empathy. Through meticulous research and musical analysis, Grasse illuminates how Dolphy's vocabulary—leaping intervals, bird-like calls, and explorations of harmony's outer edges—emerged from historical and personal circumstances. The biography traces Dolphy's evolution from a Los Angeles studio musician to a vital force in New York's avant-garde, examining how his collaborations with Charles Mingus, John Coltrane, and others energized and complicated jazz's tumble into modernity. Against a backdrop of hostile criticism and limited commercial prospects, Dolphy maintained an unwavering artistic vision until he died in Berlin in 1964, leaving behind recordings that continue to challenge today’s aspiring jazz musicians.

Lawrence Peryer recently hosted Jonathon Grasse on the Spotlight On podcast for an in-depth discussion of Eric Dolphy and the process of writing of Jazz Revolutionary. Topics included Dolphy’s formative years in Los Angeles, his friendship with John Coltrane, the legacy of the Village Vanguard recordings, and his explorations of the 'Third Stream.’ The interview has been edited for length and clarity for this article. You can listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On podcast player below.

The Light Bulb Effect

Lawrence Peryer: Your multidiscipline background as an academic and a composer—I'm curious how your technical understanding of music and instruments shaped your approach. How would that differ from how a more journalistic biographer might approach this?

Jonathon Grasse: I had to walk back the technical stuff. I worked with some people in the publishing process, and it was deemed better to focus on a broader general audience that would appreciate every page of the book.

There are no music examples, and that's by design. I appreciate journalistic writing in that it's engaging, typically with fresh language and an inviting tone. I do my best but struggle with that side of my writing. A compromise came with the skeleton of the project itself, which is a day-to-day, diary-type approach to accounting for his recordings, whereabouts, and interactions. The technical side of the academic background receded into the back of the room.

Another challenge that complicated the approach was the lack of primary sources. Dolphy has been dead for sixty years. I did contact people like bassist Richard Davis, who was still alive. However, due to his advanced age and the nature of some of his answers to my questions, it wouldn’t have been appropriate to use any interview material. There are very few personal contacts, and that isolating factor left it up to me to structure this in a very streamlined, direct, timeline fashion.

Lawrence: I can relate to that—how the advancing age affects things, and there's only so much we can expect from people to recall events with clarity that happened a literal lifetime ago.

I'm very curious about this day-to-day or diaristic aspect, which requires going through session dates and personnel notes. Were there things you encountered where you thought, "Wow, that's a missing piece for me," or any discoveries?

Jonathon: Putting everything together was regularly like a proverbial light bulb effect through writing. It was like, "Oh yeah, I see now he did leave the Free Jazz session and go straight to Englewood, New Jersey to record another album that day."

There are plenty of anecdotes, like assuming Eric was part of an Ornette Coleman concert in Cincinnati. The promoter billed it as "free jazz,” and all these people showed up expecting no admission. Ornette apparently canceled out of frustration that, no, it wasn't free. Even a very recent Ornette biography says Eric was there, but he wasn't—he was in England touring with Coltrane in November of '61.

The timeline reveals interesting things about Dolphy’s time in and out of the Mingus workshop. He wasn't in consistently month after month, year after year. He left several times whenever he could for his own career. As far as I understand, he would leave when he could, and he was grateful for the livelihood when he was welcomed back, which was any time he was available. I didn't want to contrive anything, but there's something to say about that relationship and the one with Coltrane. I hope future writers who come across memoirs or have some other sources extend an understanding of Dolphy's work with Mingus and Coltrane because there's still more out there.

The Color Line

Lawrence: Could you talk about Los Angeles in the '40s and '50s regarding Eric Dolphy’s musical development and foundational work there?

Jonathon: Certainly. I think it would be appropriate to start with his parents—the fact that Eric was the only child of loving immigrant parents who cherished the thought of him becoming a professional musician. They encouraged him to take music seriously, and he did from age six onward.

His coming-of-age period was filled with public school music opportunities and wonderful music teachers. He excelled. By age thirteen or fourteen, his music teachers encouraged him to become a multi-instrumentalist. They would say, "Try the flute now, the oboe, the alto sax." He absorbed positive encouragement and support through public school music programs.

Moving on through into the '40s—those were amazing times. He was a fan of R&B, he loved classical music, and there was the rise of be-bop. Dolphy had adolescent dreams of playing oboe in an orchestra. But there was the color line—that phrase is a sad reminder that he would have had zero chance of making it through the ranks. That's a painful reality to come of age in segregationist, racist America. There's his rejection by a USC summer program for student musicians—he was rejected because he was African American. I include that in the book without documentation, but many reference it.

When he comes of age and becomes a jazz musician, he has Central Avenue. He has Gerald Wilson. He has Lloyd Reese, an independent music educator. And, of course, his friends and colleagues in the clubs and his experiences with Roy Porter and the 17 Beboppers are still educational, even though he's out of high school.

LA figures strongly in any Dolphy story because of the ample musical broadening and opportunities it offers. The entertainment industry is certainly significant—Buddy Collette being a primary mentor while also being a pioneer African American breaking into the industry and coaching Dolphy on his multi-instrumental development. He helped Dolphy become a valid young musician, taking entry-level gigs, whether for rock and roll or session work for a crooner.

Between Buddy Collette, Gerald Wilson, and Jerome Richardson—who to me somehow remains a mysterious persona but was an accomplished musician and great session player and multi-instrumentalist—that group provided the perfect upbringing for a still-young musician with great chops, reading skills, and tone on three instruments, which is pretty remarkable.

Lawrence: I'm curious about Gunther Schuller and what you know about Dolphy's work and ability to interface with Third Stream. What did you learn about what that meant to him?

Jonathon: I think it was hugely important to Dolphy. I previously thought that the Third Stream was questionable—and I add that in my book, just as a devil's advocate sort of discounting that artistic attempt in the late '50s through the '60s. But rather than deconstructing it in that negative way, I ended up seeing and sensing that Dolphy was extremely proud of being a musician capable of entering a concert hall and playing challenging new music pieces with a conductor, chamber music instruments, and a string quartet—he loved it.

I believe the Schuller contact was a godsend for Dolphy. From what I gathered, they became very close friends and played and rehearsed together a lot. Schuller seized on this in his own artistic world by featuring Dolphy in many groups—not just in the studio but with concert music gigs: Syracuse, Carnegie Hall, Chicago, regular appearances playing challenging concert music that was the so-called fusion with jazz.

I went out of my way to include some negative reception of that in the press—a DownBeat article here or a mainstream newspaper review there that comments on "Hey, what is this stuff? What's Schuller trying to do?" And then, on several occasions, toward the end of the review, it's like, "However, Eric Dolphy was awesome." I think the Schuller contact validated Eric's hard work in becoming a master musician with broad interests in many ways.

A Lifelong Bond

Lawrence: I have to turn to the Coltrane era. And full disclosure, the Village Vanguard performances and the subsequent European tour in '61—it's my favorite music. I'm curious about your perspective on their musical relationship off the bandstand.

Jonathon: Off the bandstand, they were deeply connected friends. That goes back to '54, and it's kind of legendary, worth repeating, that Coltrane was strung out when he came through LA and was fired from the Hodges band, and Dolphy helped him out, got him on his feet. What are the details of that? I'm not sure, but I know it led to a friendship when Dolphy relocated to Brooklyn.

According to Freddie Hubbard and some other incidental comments, they all started hanging around when Coltrane finished up with Miles in 1960. Coltrane was busy gigging, touring, and recording, and he was very successful—I mean, my God, you know, My Favorite Things and Giant Steps—earning the right to call his shots with Impulse the next year. Having that position with the label, Coltrane says, "No, I'm a quintet now; Eric's playing with us."

Coltrane went out on a limb and knew it by getting Dolphy on stage. This wasn't some sort of weird favor Coltrane was offering to Dolphy for a livelihood, which, unfortunately, some commentators have suggested. Coltrane had a deep respect and admiration for Dolphy's playing, and he said so, and he backed it up by bringing him into the band for sixteen or eighteen months.

To circle back to the core of your question about their friendship—it was a serious one—I couldn’t help but notice Ben Ratliff’s comment about Coltrane keeping Dolphy’s photo in his hotel room after his death and keeping in touch with his parents. That's just a lifelong bond.

Lawrence: I can only see it retroactively, but I would argue it also opened the lane in jazz journalism. That whole—I don't know if we want to call it controversy—whatever it was, the DownBeat interview that followed that spring.

The view of Dolphy changed once the expanded editions of the albums came out. For the longest time, we just had Village Vanguard and then whatever they called the other one. What kind of reassessment happened for Dolphy, if any? How are Dolphy's impact and contributions looked at differently?

Jonathon: I tried to exploit that in the book by mentioning that many more complete sessions and re-releases have emerged. If we date that complete Village Vanguard release back to the late '90s, there are about thirty years of hearing the real Dolphy because the original releases weren't good. They did not put Dolphy in a good spot. They weren't good takes. They cut some solos. They chose a couple of tracks from the live sets that were not Dolphy at his best. Then you get the complete sessions and realize that if you were there, you saw an amazing multi-instrumentalist. He didn't bring his flute, but he had his bass clarinet and the alto sax and blew his heart out.

Opening Eyes to What's Possible

Lawrence: Do you think Dolphy’s multi-instrumentalism made it hard for people to figure out where to place him?

Jonathon: Yeah, I think he's considered a saxophonist, and of course, there are already people doubling on flute. I think the bass clarinet is that sort of third wheel, so to speak, that, on the one hand, is awe-inspiring when you realize the talents and the different challenges to play the way he did on those instruments.

Some voices suggest that it held him back or complicated people’s view of Eric Dolphy. I don't ignore that, but I don't think it hurt him. It opened some eyes as to what was possible. And what he did in the '50s with Chico Hamilton was pioneering.

Lawrence: Can you tell me a little about the choices you had to make discussing his diabetes and other personal details important to how the story ends?

Jonathon: Jeff Schwartz, who wrote the forward, pointed out in an earlier version that I allude to his death too often. I cut that back just because it's so obvious. Most readers pretty clearly understand that he died young. As far as his diabetes, I looked for sources. I tried to understand that, and it's obvious the core of the tragedy of this early death is this undiagnosed diabetes that just whittled his body away. I looked into what were some of the inevitable symptoms he was experiencing, and it's pretty awful. It wasn't just in his last days—it would have been for months that he was suffering from the symptoms.

He had oral thrush, a mouth infection in early '64 that kept him out of the workshop. Mingus had to find some replacements—he couldn't play. That healed up, and he just continued because he had to; that was his livelihood. So he's probably had some pain, which is remarkable when you hear the Mingus European tour stuff from '64 and the U.S. concerts—the Cornell and Town Hall. Dolphy is just magnificent. I mean, great playing—some of his best work, I think, is that stint with Mingus in '64.

Purchase Jonathon Grasse's Jazz Revolutionary: The Life & Music of Eric Dolphy from Jawbone Press, Bookshop, Powell's, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments