Twenty five minutes into the 2022 documentary Squaring the Circle (The Story of Hipgnosis) Noel Gallagher, late of Oasis, says, “There’s a great quote from someone…’Vinyl is like the poor man’s art collection.’”

It is a great quote. And, despite him disclaiming ownership, if you search the internet, it now appears that in the minds of lots of people now it’s a Gallagherian original. Which is just one of the odd things about his appearance in Squaring the Circle.

But we’ll come back to Noel later…

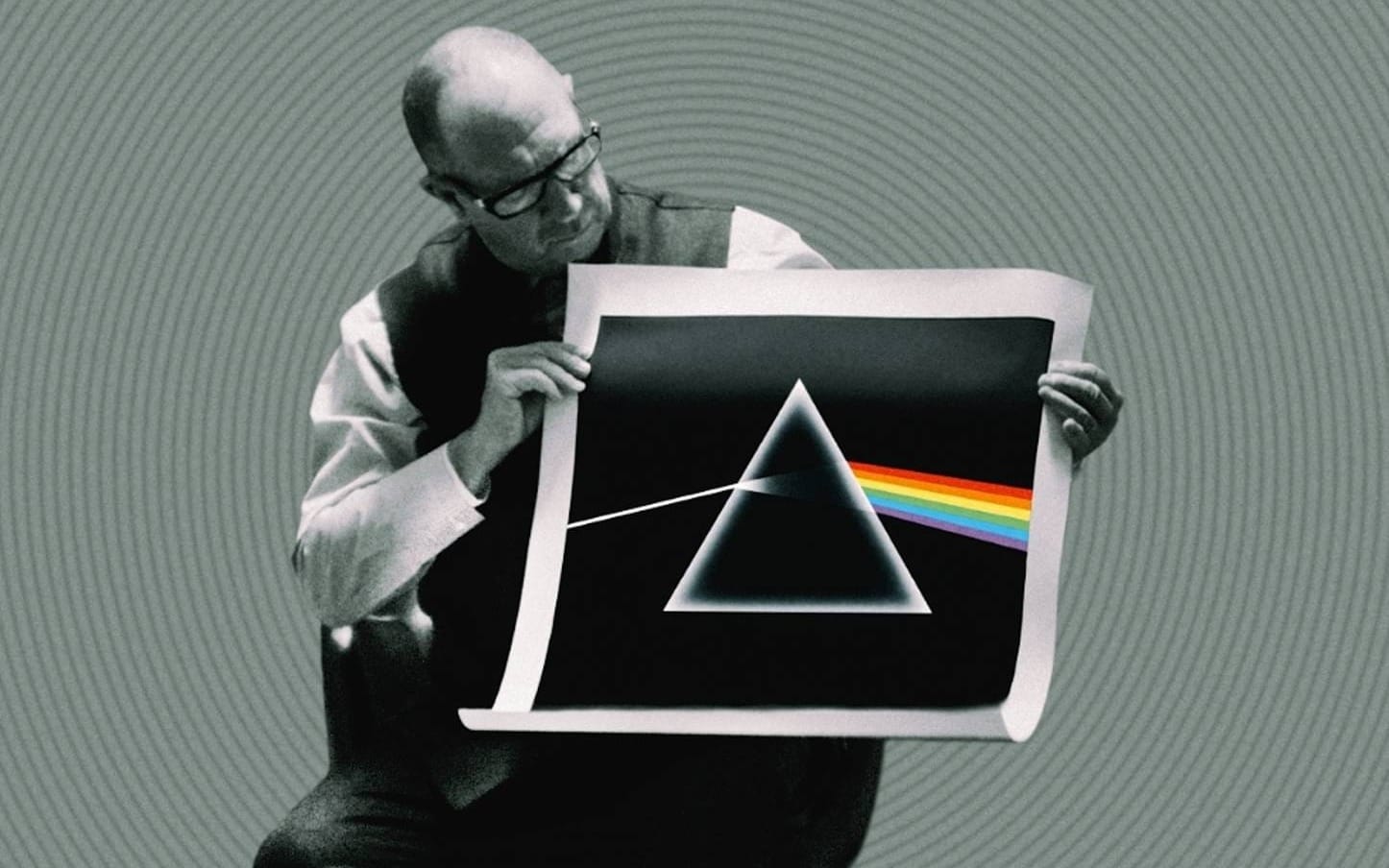

Hipgnosis was the influential London design studio behind some of the most iconic album covers of the prog and prog-adjacent '70s. Most famously, they did every Pink Floyd cover between 1968 and 1981. They also designed covers for Yes, Genesis, Electric Light Orchestra, Styx, Black Sabbath, T. Rex, Def Leppard…

Then there are poppier outliers like Olivia Newton-John, Leo Sayer, and Wings. And that still leaves artists like the Winkies (the little-known pub rockers who backed Brian Eno’s only solo tour until he suffered a collapsed lung), Hot Chocolate (clearly hoping a Hipgnosis cover could return them to their “You Sexy Thing” peak), and John Williams (the classical guitarist, not the guy who scored every blockbuster movie you loved as a kid).

The studio’s flame sputtered out in the early ‘80s. The story of their demise amounts to an acknowledging they'd become too associated with everything the punk and post-punk eras professed to be against. It’s a shame.

Seven years before Johnny Rotten put on his famous “I Hate Pink Floyd” t-shirt (which makes an anecdotal appearance in the film) two guys named Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey “Po” Powell were in art school. Then they were asked by some old friends who had a band to make an album cover.

In Squaring the Circle, Po goes into some detail about the process of making that cover. It was for Pink Floyd’s second LP, A Saucer full of Secrets. The way he went about it sounds very much like a precursor to the Xerox-based paste-ups that would later be a staple of DIY punk design, and that kind of spirit would infuse much of their future work.

Storm died in 2013 but appears in archival footage. And there sure seems to be a lot of archival footage, not surprising considering the two had planned on being filmmakers. Instead, they co-founded a design studio specializing in record covers. The name Hipgnosis, as interview subjects make perfectly clear, either was or wasn’t coined by Syd Barrett.

At multiple points in Squaring the Circle, people make a point of mentioning that, unlike Po, Storm wasn’t interested in money. He really was in it for the fun and the creativity. Po also wanted those things, but on the other hand, he also liked the money.

In addition to Po, a parade of ‘70s arena rock royalty is pulled out of the vault to reminisce. Three members of Pink Floyd, two from Led Zeppelin, one ex-Beatle, the only constant member of 10cc, and more…

To a certain type of music geek, this is fantastic stuff. I am that type of geek.

Watching it humanized Po, Storm, and others who I’d only known of as larger-than-life names. Then, of course, there are the required tales of excess once Dark Side of the Moon launched both Pink Floyd and their album designers into the highest orbits of the music business. Some are legendary and well-known, like the incident with the runaway inflatable pig, but others were new to me.

The tale of 10CC's Look Hear? could be a poster child for '70s rock's everyday indulgences.

To fulfill Storm’s vision, Po flew from the famously sheep-littered UK to Hawaii, where there are very few sheep. Once there, he managed, with some difficulty, to find a sheep.

Then, he convinced it, with the help of Valium, to sit on a psychiatrist's couch. But he had to have it made because he couldn't find one to rent. Oh, and he did this on a beach in front of crashing surf.

Now, you can't tell me that there wasn't an equivalent location somewhere closer to London he could have used, which would have been cheaper and less logistically challenging. Portugal, perhaps, or Spain. Or that they couldn’t have just set up a backdrop in a sheep pasture and matted the beach in. But Hawaii was part of the vision, so it had to be done there.

The kicker is that on an album cover dominated by the words "Are You Normal?" — which is not the title of the album — the sheep image is only the size of a 35mm negative. Except in the US. There, the record company, distrusting the intelligence of the record-buying public, freaked out and replaced the design with a full spread of the sheep on the couch.

I simultaneously scoff and wonder, "How come I never had a job that let me get away with stuff like that? Maybe I'm normal?”

Gallagher’s borrowed quote does ring true. For pre-CD dedicated music fans, the covers of records leaning in rows against the walls were like the artworks fancier people hung higher up on theirs. Being in someone’s home for the first time meant sitting on the floor, flipping through record jackets.

He describes taking the bus back from the record store, staring at records “by the Smiths or the Jam…” all the way home. I may have been 4500 miles away from Manchester, but conceptually, I was right there with you, Noel.

Records weren’t just sounds. There was the artwork, the credits, the lyrics…all part of the experience.

At 14, I read every single word on the cover of XTC's Go 2 album. And it was very, very wordy. On the back, the design was credited to Hipgnosis. I got the pun. And that made me feel like an insider.

Soon I started seeing that credit on other albums. If I was judging them solely by their covers, I might have bought them, but for the most part, they weren’t artists I was ready to spend my scant money on.

Many Hipgnosis covers defy explanation. David Gilmour describes the Atom Heart Mother design brief as “Storm said ‘…What’s the most meaningless thing we can do? We’ll just get a picture of a cow and stick it on there.’”

Others are high concept. The cover of Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy owes its inspiration to the Arthur C. Clarke sci-fi novel Childhood’s End.

Then there are the puns. 10CC’s Deceptive Bends turns a roadside warning into a diving groaner.

Despite Storm’s objections, the studio wasn’t above simply doing what the artist wanted if the money was good. He once walked out on Paul McCartney, and if you’ve ever seen the cover of a Wings album, you’ll sympathize. As 10CC sang, “Art for art’s sake, money for God’s sake.”

For all this variety, it’s weird when Gallagher cites the Smiths and the Jam. Hipgnosis never worked with either one. The closest they came was that XTC cover and the cover of Throbbing Gristle’s 20 Jazz Funk Greats. That last one was only because Throbbing Gristle member Peter "Sleazy" Christopherson’s day job had taken him from designer to third partner at Hipgnosis.

It’s not in the documentary, but that anomalous XTC cover is important. It shows just how well Storm understood what Hipgnosis was doing.

XTC was idiosyncratic, out of step, referential, and funny in a way not many first-wave UK punks shared. It was like they were already post-punk while punk was still in its first flower. They showed up in the middle of the London punk scene as outsiders from Swindon, a city that, to many Brits, exists solely to be made fun of. Virgin Records advised them to disguise their local accents so London punks wouldn’t think they were uncool. They did not do that.

Storm understood them. And he turned that understanding into the first record cover I loved. The front of Go 2 is a wall of 12-point white typewritten text on a black background. It begins:

“This is a RECORD COVER. This writing is the DESIGN upon the record cover. The DESIGN is to help SELL the record. We hope to draw your attention to it and encourage you to pick it up. When you have done that maybe you’ll be persuaded to listen to the music – in this case XTC’s Go 2 album. Then we want you to BUY it.”

Then it goes on. And on.

It’s a thesis statement of anti-marketing as a form of marketing presented in an anti-design style that’s unashamed to admit it’s actually design.

Anti-design had already established itself on UK punk record covers through examples such as the Sex Pistols' ransom note paste-up lettering, the Jam’s spray-painted name, or the Clash’s torn-edged photocopy photo. But the class of ’77’s anti-design rebellion had more in common with Hipgnosis’s iconic design sense than punk’s ethos allowed it to admit.

There’s a strong element of the 1920s Dada art movement in Storm’s concepts. Po’s more methodical focus on process, technique, and commercial viability makes him a reasonable Man Ray analog. The anti-intellectual branches of punk may resist acknowledging the influence, but many of its early shapers, both on- and off-stage, were drinking from those waters.

None of this is in Squaring the Circle, of course. In Hipgnosis’s catalog, one album cover for a band that never quite made it past cult favorite status is a barely noticeable blip. But it’s a blip that caught me at exactly the right moment to get me interested in album cover design, as well as the Ouroborosian paradoxes that come with being a consumer who understands how marketing works.

For all the things that work in this documentary, the presence of Noel Gallagher is at first baffling. It wasn’t until after the documentary finished that I saw why he was included.

Oasis, particularly their first three albums, stood out in the '90s for their mannered and posed sensibilities in a deliberate rebuttal of grunge style. Just as Gallagher never met a '60s riff he didn't put into one of his own songs, he was consciously basing the Oasis album covers on the '70s heyday of Hipgnosis.

But in the edited film, no one says any of this, least of all Gallagher. He says he likes Hipgnosis's work, that he couldn't have afforded them, and that he regrets being so hasty when picking the cover for (What's the Story) Morning Glory?

Oasis's covers aren't awful, but they feel more than one step removed from the mad creative sparks that Storm shot out like a Roman candle. Like the band's music, they are revivalist, in love with a style and dismissive of the idea that there should also be substance to justify it.

Noel Gallagher might not agree, but the cover of Nirvana’s Nevermind(conceived by Kurt Cobain, art direction by Robert Fisher) was closer in spirit to Hipgnosis’s best work than any Oasis album. And it could be seen as distilling the content of Storm’s cynical thesis on the G0 2 cover into a single image.

If you don't make the connections yourself, the presence of Noel Gallagher as another talking head alongside Paul McCartney, Roger Waters, David Gilmour, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, Peter Gabriel, et al makes no sense. 10 years after Hipgnosis's last album cover, he wasn't even a working musician but a roadie for Inspiral Carpets.

But good luck trying to tell Noel Gallagher to look at the camera and say that he asked his cover designers and photographers to mimic Hipgnosis. That's not going to get you anything but a torrent of Mancunian invective. His presence isn't unwelcome as long as it’s put in context. But it’s up to the viewer to figure that context out.

Should documentary filmmakers occasionally stop relying on interview subjects to explain why they are there and instead insert a bit of narration or a title card or something to do it?

Definitely Maybe.

Comments