(This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.)

LP: Thank you for making time today.

Kevin Sun: Absolutely. Excited to be here.

LP: I wanted to learn a little bit about your musical biography, starting with where you're from, your musical upbringing, your early musical exposure, and your interests. I'd love to learn that about you.

Kevin Sun: Sure. I grew up in central New Jersey in a small township called Montgomery. It's right next to Princeton. It's pretty rural, suburban, and very quiet. I started playing music and taking piano lessons when I was eight years old. My parents made me do it, which is sort of a classic thing, and it's the same for many Asian Americans.

And so did that in fourth grade. I started playing saxophone as part of the band program. So I was ten, and then I got into playing jazz when I was around twelve or thirteen. A friend of mine gave me a CD for an enrichment music appreciation class. It was a burned CD with a bunch of jazz recordings, and I was just curious. I had never listened to jazz before, but I heard "The Girl from Ipanema." The saxophone solo just transformed me in some deep way.

I didn't realize it was a saxophone. I heard it, and it was a beautiful sound. I couldn't tell what it was, really, because my idea of a saxophone was a fourth-grade band saxophone, which was a sixth-grade band at that time. And so I became obsessed, and I switched to the tenor saxophone, and it all grew out from there.

I kept playing and started to take jazz lessons in terms of improvising. There's a great local teacher, Laurie Altman, who used to live in Princeton, and he taught at Westminster Choir College. He taught composition, but he played jazz in the '80s and '90s. He lived in New York City, and he was playing on the scene. He's on some records, but then he moved to the suburbs, and he also had this separate life of being a serious Western classical composer. That's why he was teaching that.

He moved away from jazz, but he was a great player. He taught me a lot. We basically just played. He introduced me to a lot of music and played tunes. He gave me a lot of conceptual ideas about improvising and thinking about just playing music.

Then, I went to music school. I did my undergraduate at Harvard, where I studied English. At the same time, I was taking music courses at the New England Conservatory, and I did a master's degree there. I moved to New York in 2015.

LP: Does your undergrad experience suggest that you had an idea that music wasn't going to be a professional pursuit for you?

Kevin Sun: Definitely. Late in high school, I just wasn't sure. I love music, and I still do, but at that time, I wanted to keep my options open. It's funny because that perspective has been my whole life. It's still true today, but I was just curious what else the world had to offer.

The opportunity to study at a world-class university and be exposed to many different ideas that weren't just musical appealed to me. That is why I chose that path rather than going straight to music school or trying to play music professionally.

LP: I appreciate that this may be a little bit of a cliche or hack question, but did your undergraduate studies bring anything to your musical life? Is there any influence or perspective that studying the humanities that way, studying English in particular, makes its way into your composition or your improvisation?

Kevin Sun: It does. I think it manifests in a lot of different ways. Maybe the most obvious is song titles. I like to have wordplay in my song titles, and I think this is just very personal to me. Still, I feel like sometimes there can be a lot of lazy titling that happens after the fact in terms of certain song titles that seem just to pop up again and again, even though the music may be great.

I think the person who wrote the song was sort of an afterthought. For me, I kind of love sometimes just starting with the song title, having an idea, having some phrase that seems really fertile, or something that gets my imagination going. There are certain composers I like, like Henry Threadgill, who are amazing composers and artists but also have amazing titles. I think they can go hand in hand.

LP: It's interesting to me that you go right to the song titles. Listeners to this podcast will recognize that I bring that topic up a lot with instrumental artists because I'm very curious about the role of song titles and the different perspectives that artists have.

Some say what you just said, which is they start with a song title or a theme, and others, it's much more slapdash, to the extent of even letting somebody else name the songs or not really knowing what the song should be titled until after they play back and hear it a few times.

I wonder if, as an extension of that, there is a narrative element? Is narrative part of your improvisational construct?

Kevin Sun: It's an interesting thing in improvisation because it's all emergent. You can't plan it out ahead of time. You can have a sense of how it might go based on having played a certain song a bunch of times with the same people.

Generally, when I think about narrative as a composer and as an improviser, I try to see it in the broader context of the song. As a composer, I'm thinking about what episodes and what sequence of events are going to happen. It really varies, depending on the context of the band—if it's a smaller group versus a larger group, how much pre-composition or fixed material do you need ahead of time?

You see extremes all the time, and a lot of it can be a matter of taste. Some people like to hear, or they want to go in with no preconceptions or predetermined materials and just let the narrative be totally emergent, 100%, which can be cool, and it can also be totally boring. It just depends on what happens with that group of musicians in that room with that audience that night.

I think of myself as wanting maximum expressive possibility within a framework. I also want the framework to be maximally interesting in terms of having something formal that the musicians are really digging into. I want it to have as much complexity as I can bring in sophistication as a musical thinker and composer without totally putting the musicians into handcuffs. That's the tightrope that I'm trying to walk. That's how I see myself, at least.

LP: Could you dive into that a little bit more or make that a little more tangible for me? How does that manifest? Is that direction? Is that prompt? What's the direction the musicians are getting?

Kevin Sun: For instance, a lot of my songs, especially in the past five years, have a pretty heavy rhythmic component. To go a step further, it's metrical. It's a meter. It's actually how long, conceptually, certain things are happening, like bars of music.

A lot of times, we keep a consistent meter because that helps to make it more conducive to grooving, which is huge for jazz, which is fundamentally dance music. But what I'm interested in and have been interested in is writing music that essentially uses mixed meter a lot. So it changes meters constantly, but I want the effect to be for the listener, and I want it to be this sort of interesting flow of musical events happening in an asymmetrical kind of way, which I think is closer to our experience of reality anyway. It's not all totally regular.

The challenge here is to try to make it groove. So, as a musician, as a person executing the material, you want to hide the seams of where the bar lines are. You want it all to flow, and it should be obvious to the listener that all the musicians are moving together through time and through the music. But what exactly they are referring to might not be obvious because we're hiding it as we're improvising.

I think the best drummers and bass players find a balance of delineating parts of the structure and the form but also elaborating, embellishing, and adorning it, if that makes sense. That's what I'm going for.

LP: You made the comment about jazz being essentially dance music, and it's another topic I love to discuss with instrumental musicians or jazz musicians, this notion that if you have an awareness of the history and where it came from and how it went from the dance hall to the club to the conservatory. It's just becoming something that people sit down and watch and analyze as opposed to a seatless room with people dancing and the role that World War II played in the demise of the big band.

The transitions of jazz over the last, really its whole life, the last hundred years or so, is fascinating. I'm more familiar with your music than I am with your writing. Still, I'm very interested in the fact that there's that important element to you of analysis, commentary, connecting with the history and the lineage. I wonder, rather than me declaring the role that plays for you, if you could talk a little bit about the why of the writing in your work.

Kevin Sun: I used to be more involved in writing about music, and I think in the past five years or so, I've pulled back from it because it's very easy to get pigeonholed. I feel like in New York, maybe five years ago, I had the sense that people thought of me more as a music writer and blogger than a saxophone player and composer. There was a conscious decision on my part not to be so public about it.

I still think about music, and I have a notebook, and I write down thoughts and things, but I'm not advertising that, so to speak, as much. I started a blog in 2012, so I was partway through college. I was basically inspired by Ethan Iverson's blog, Do the Math, which was his musical diary of whatever he was checking out, what he was curious about. It eventually became more formal in the sense that he would do heavy-duty interviews with serious artists who were heavily prepared ahead of time in terms of listening through an artist's discography and having very specific questions.

That just appealed to me. I was already studying music and trying to learn as much as possible. I was curious about history, and I just figured, why not just share whatever I learned? I was discovering or thinking that I was discovering because I thought if it's helpful to me, it might be helpful to someone else. Also, other people can share their perspectives. I might be wrong about how I'm interpreting something, or maybe I'm missing some facts. So, I just wanted to put it out there.

At that time in the early 2010s, my sense was already a sort of earlier era of the internet with blogs and a lot of commentary on the way down. But there was still enough that I got a lot of useful feedback from people on Twitter, older musicians, and other things like that. So I just kept it going essentially until I moved to New York, and then I got pretty busy with other things. So I pulled back on it.

LP: The Ethan Iverson analogy interests me. I love hearing an artist's voice through that medium. When the analysis, commentary, and contextualization are in that tradition, it's such a unique vantage point that I think it only adds to the listening experience. It's another way to approach the artist.

Kevin Sun: It's one of the best genres. I think writing from artists as a genre in itself, musician-to-musician interviews, that's where you get the deep lore and the juiciest material because those are the people who lived through it and have this really deep immediate connection to it.

This is not to say that critics or people who are not necessarily practitioners don't have something to offer. They can be extremely valuable, especially with a level of detachment from the artist. But there's something special about getting it straight from the source.

LP: When you were talking about hearing "Girl from Ipanema" and the Stan Getz sound, I understand what you were saying because I'm just hearing that in my inner ear at the moment. It's just a different sound. But I wonder, what was the sixth-grade saxophone band sound? What am I supposed to take from that?

Kevin Sun: So I was playing alto, and I can remember, by default, most people have this mouthpiece that comes with the student instrument. It tends to be really closed. That means the sound is going to be really pinched generally, nasal, and relatively difficult to tune. The sound that I heard on the recording was this glorious, breathy, warm, rich sound, dry also, but something about it. There's like a beautifully half-lit light or something with beautiful shadows. That was what it felt like to me. It was more like a cloud peering through, the sun peering from behind a cloud. This epic, dramatic, sublime image. That's what I heard.

LP: It's one of those rare recordings that combines the musician's appearance with the attributes you just described, whether it's the relationship with the instrument or the equipment itself being just right and wonderful engineering. It's just one of those moments when it's clear that it's all highly competent practitioners who came together to make a record like that.

Kevin Sun: Have you heard the story about the mouthpiece?

LP: No, please!

Kevin Sun: So I read that when he went to Brazil, his horn got stolen from the back of a car, or he left it in a cab. Something happened. So he didn't have the mouthpiece that he normally used. He had to get whatever was available nearby at the last minute, and he just made it work.

I think that's part of it because, listening to all his other recordings, there's a degree of comfort where the sound is breathy, generally speaking, for him. But on that particular recording, he just used whatever and made it work. That kind of blew my mind because, for me, that's a lesson that sometimes it doesn't really matter what the equipment is, or being thrown into an unfamiliar situation will lead to something even better than what you expected.

LP: That's not dissimilar from the Keith Jarrett story with the Köln concert, right? With the broken piano and making what, at the time, was the best-selling jazz album. That's just incredible.

It goes back to what you were talking about in your improvisation. The universe imposes constraints, whereas you're bringing some guardrails or some parameters within which to improvise so as to add focus or sharpen because the universe is so big and so sprawling otherwise. How do you keep the improvisational moments in service of the vision and the composition? By taking away variables from the players, you sort of free them.

Kevin Sun: Just having constraints, this is another thing I had in college, the idea of constraints when you're writing or something. It's counterintuitive, but you're way more free if you have some sort of restriction because then you just have to do it. Again, striking the balance of how much is productive versus how much is counterproductive. It depends on genre, too, but one of my newest resolutions is that I only want to write as complexly as I need to. Basically, I want to try to keep it as simple as I can as I'm writing because that's a thing that I've been working on over the years, trying not to overwrite.

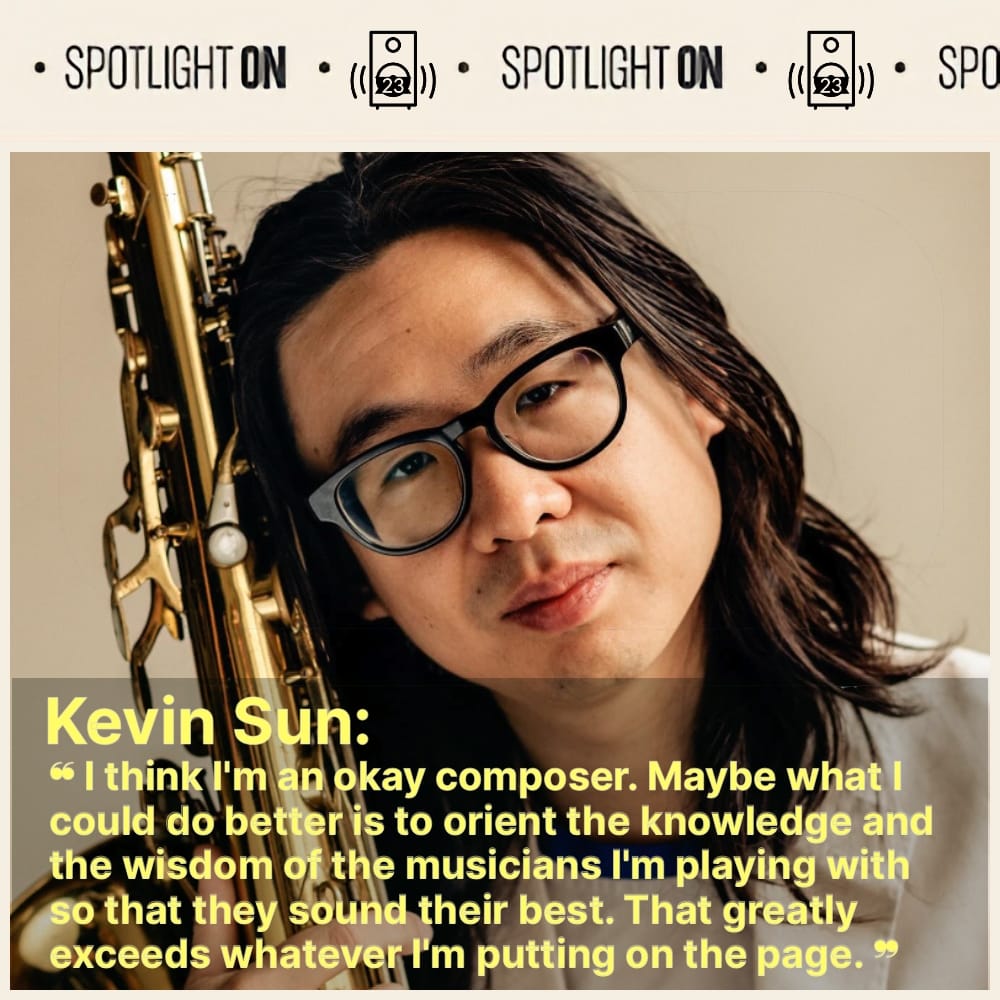

I think being in New York also helps you with that because when you realize the caliber of the musicianship and artistry of so many musicians here, almost all the time, I feel like the musicians I'm playing with, they're improvising stuff that's way better than anything I could write. And so that's what I want to harness, really. I think I'm an okay composer, but maybe what I could do better is try just to orient the knowledge and the wisdom of the musicians I'm playing with so that they sound their best because that greatly exceeds whatever I'm putting on the page, in my opinion.

LP: It's interesting that you're thinking about composition that way because something that struck me in listening to the Depths of Memory albums is just how thoroughly composed the music is, but it's not impenetrable or dense. It straddles this line of almost, and again, I'm not a musicologist or a theorist, so I apologize if I get it wrong. Still, you can hear the compositional elements and even maybe a classical influence or modern music; it's all there, but it's not inaccessible. It's something that I really enjoyed about listening to those records.

I'm curious a little bit about the structure or process of the Depths of Memory project. There's a volume of music to start. What led to the release strategy, if you will? Why was it broken up? Why was it presented in these volumes? How were you thinking about the presentation of it?

Kevin Sun: The release of this double album is pretty different from anything I've done before, and the biggest reason is that I started working with the folks at La Reserve Music. La Reserve is a record label, but it is also a specialist in digital distribution. They have great relationships with streaming platforms and curators for jazz at Spotify, Tidal, and these sorts of places.

I had pitched a separate record to them for release. At the time, we had never met or spoken. They were basically like, "We like the music a lot. We're not 100% sure we can fit it in, but send us whatever else you have." I sent them the double album because it was ready to go. I was going to just self-release it, and they said, "We love this. We want to put it out. But how do you feel about this strategy of extending the release cycle over a longer period of time?"

They told me, "We can tell you put a lot of time and effort into this. From our experience, the best way to get the best results in terms of perception and visibility is to extend the release cycle. So, have more singles and build up some buzz. If you're comfortable with that, we think that would be the ideal approach."

At that point, the music had been ready for at least six months. It was totally mastered and ready to go. I had composed a lot of that music, and I started composing that music over five years ago. It was a really long process. So I didn't really mind. I figured if I've already waited this long, waiting a few more months, if it is going to do what they think it will do. And I was really pleased with the results of the campaign. Both La Reserve and I were really satisfied with how it turned out.

LP: It borrows a lot from the way pop music is marketed, a longer campaign, dripping singles, keeping a narrative going. I think that's exactly right. If you could easily drop all of this music that you put so much into one day, and then if the stars don't align, you've missed your window.

Kevin Sun: That's really difficult. I knew going in that they had a proven track record of really helping their artists grow in their careers. So I just totally put my trust in them, and it worked out. We're continuing into 2024 with future releases, which I'm excited about.

LP: Can you tell me a little bit about memory as a motif in your work?

Kevin Sun: Obviously, it's front and center in this album title, but this album and also the previous double album, The Sustain of Memory, I'm just thinking of that as times in my life in terms of what I would consider early adulthood, finishing school, moving to be on my own and work, and then thinking back on my childhood and the town I grew up in.

I just had a strong feeling of nostalgia at that time, and I wanted to try to express that creatively through music. Memory is a fixation for many writers, thinkers, and people. It comes and goes at different points in your life, and different things can trigger it.

The first album was about early adulthood. This most recent album was a really intense memory experience while dealing with the pandemic and isolation. For now, I'm good at wrestling with memory as a motif, but that's where it falls into my work.

LP: In the context of this project in particular, did you know you were writing for this ensemble?

Kevin Sun: This was my band and my project. I knew that I wanted to continue the same quintet that was featured in The Sustain of Memory. There were some personnel changes due to the availability of musicians, but I knew going in that I wanted Adam to play trumpet on a good portion of it. I knew the rhythm sections that I wanted, and that was going to color the sound of the music a lot.

LP: The rhythm section is so delicate at times that it's really impressive, but the piano work stood out to me as well.

Kevin Sun: Dana is incredible. Dana Saul is the pianist. I think more people should know about what he's doing.

LP: Incredible. I made a note of one track: "Interior Choruses." If you don't mind me complimenting you, I heard there's a Monk element to the composition. There's a sort of angularness to it. I could put that one on repeat. I might this weekend. I might be driving your streaming numbers on that track.

Kevin Sun: I appreciate that a lot. Please do. (laughter)

LP: I'm really taken with the fact that you have this regular gig at Lowlands. I can't help but think that's a great platform, knowing you have this consistent place. I've watched some of your social media where you talk about working out things to perform. This seems like a luxury in artist development or the development of an artist.

Kevin Sun: For me, that's the holy grail; it's the ultimate luxury. I can't take it for granted because I feel like ever since I was a teenager, I've wanted a weekly gig somewhere where I could just work out music on my terms. So I just feel so lucky to have this place.

Lowlands is a dive bar in Gowanus, two blocks from my house. I started playing there on a monthly basis the year before the pandemic. I learned about the bar through Walter Stinson, the bass player on many of my projects. He used to bartend there just as a gig.

Through Walter, I met the owner, John Niccoli, who is a huge supporter of the arts. He creates music on his own, but he's also just a musician, a massive music enthusiast for all genres of music. He knows a lot about hip-hop and electronic production and stuff like that, but he loves jazz. He grew up listening to it, and he was open to it.

So we did a monthly gig. Pandemic happened. There wasn't anything happening. Then, I was going back to the Lowlands just to hang out in mid-2021, and it came up. John was sort of like, "Hey, how about some live music? What do you think about that? It might be fun. Bring some business back in here."

I was down, and we tried it. It went from twice a month to every week, essentially in September 2021. He just said, "Come back every week." It makes his job a lot more enjoyable in a way because there's something to look forward to; aside from just doing the job, there's exciting music happening, and the bar can afford to put out a bit of cash.

Later, we received more help from an organization called Keyed Up. It's a nonprofit that supports many gigs in New York and other cities. For instance, they support many of the gigs at Bar Bayeux, an amazing venue in Brooklyn.

Through a mutual connection, I was able to get them to help out, I think, starting in 2022. That made a big difference. So it's been full steam ahead since then, and I'm just trying to work out music there every Tuesday.

LP: That organization helps the artists get paid and relieves some of the venue owner's burden.

Kevin Sun: Exactly. It depends on the venue and the deal they work out, but essentially, they help to provide some funding to offset the venue's burden. It's amazing work. I'm glad they exist.

LP: Do you have a sense of who the audience is for those gigs? Do you have people that are coming to see you versus hitting their neighborhood local spot? Is there a mix?

Kevin Sun: When I started, and it's still like this a lot, Lowlands is not in a place that attracts a lot of foot traffic. It's on 3rd Avenue. It's very industrial. People love it because it's a neighborhood bar, relatively quiet, with a lot of regulars. It's not pretentious at all—it's the opposite of pretentious.

When I started, I played for mostly regulars, friends, and people who were just passing through. Then, over the past two and a half years or so, as we've been promoting the gigs more and more, more people have come to check out the music.

But I like that it's a mix because it forces you to deal with—I don't know how to express it in a good way—but it's like the old school thing of you have to win over the audience. You can't expect them to care at all about what you're playing. You have to communicate it through your instrument and through the energy that you're sharing from the stage, which is not even a stage; it's just a corner. You're standing on the same level as the people who are listening to you.

So you're meeting them eye to eye. You also have to read the room. If you want to play a ballad, you kind of have to earn it because people are having conversations, but you can pace it in such a way that when you get to that moment, everyone stops talking because they can tell it's something special. When that works out, it's an amazing feeling. You feel a real connection.

LP: I can't help but think hearing you describe that, the experience of doing that week in, week out is going to prove so valuable as your career unfolds and expands. Those lessons are what makes a musician a showperson, what would allow them to command a bigger stage or to understand how to build a rapport with an audience. That sounds phenomenal. It's like a masterclass.

Kevin Sun: I think it's the thing that used to be way more common, and unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, economic and cultural, there just aren't that many opportunities to have to do that. Especially with conservatory training, there's no replacement. You can get the technical skills there, but the other part, which is just pacing a set, figuring out how to relate to the audience, intangible things, you really have to do that in person, live, and you have to fail and learn from your mistakes and try things out and see what works.

In recent years, there have been a ton of venues in Brooklyn that have that nice mix of people who are not there specifically for the music but who are maybe receptive to it. Bar Bayeux is a place where the jazz is front and center, but there are still lots of just folks from the neighborhood who know it's a great cocktail bar and a nice ambiance, so they want to hang out.

You can see people, I've seen it going to shows there, people who are clearly not there for the music. But then, over the course of the set, they're drawn to it because of the magnetism of the people performing. Ornithology Jazz Club in Bushwick is the same way, where there are a lot of people who might have just heard of it because they know it's a hip place. People like to hang out there. It's a nice vibe. But then, when they actually experience the music, something changes, and you can tell that they're being drawn in. So it's an amazing thing.

LP: Are any of the places you mentioned all 21 and over? Or is there a way to reach a younger audience?

Kevin Sun: I guess because they're bars serving alcohol, they're mostly 21 and over. That's a good question, reaching the audience that way.

LP: This is another theme that comes up a lot in the conversations I have here, which is that it's been fascinating to watch over the last, let's call it, decade or so, that jazz and instrumental music has really gotten back into the culture in a way that it wasn't for a long time.

A lot of it is through youth-oriented movements, whether it's hip hop or some of the stuff coming out of the Los Angeles scene, where it's just more baked into electronic culture. It's so exciting to see, and it's great to have young people be able to engage with it live as well.

Kevin Sun: It's essential. We really need that, or else music is just museum music. It's funny that you say that because I feel like this album, Depths of Memory, is the artiest expression of my music. We played the music sometimes, a few times at Lowlands, and it worked.

Another thing that I've learned is not to underestimate the audience because you can play really experimental, sophisticated, avant-garde stuff. But as long as your heart is a thousand percent in there and it's coming out the right way, people will get sucked into it.

Tim Berne, who also lives in the neighborhood, has been playing at Lowlands every Thursday. I've seen him play some of the most intense, really noisy avant-garde stuff. People just love it, and it totally works. So that's one thing I've learned—don't underestimate the audience.

LP: It's funny to see that phenomenon because, especially with the horn player, I've been in environments out here where I've seen what I would call an older crowd really be responsive to somebody overblowing and getting them like they're channeling John Zorn or something.

People respond, especially live, when you can see the fire of the performer. It's much different than listening to even a recording of avant-garde music because when you see the performer doing it, you realize just what's going into it.

Kevin Sun: I much prefer to see noisier, avant-garde, experimental, improvised stuff in person whenever I can, as opposed to the recording, because I think that element is just so important. There's a theatricality to it and the human drama of just how extreme you have to push your body to be able to produce some of the sounds that are coming out.

Unless you see it and you hear the sound waves rippling off walls and in and out of your ears, it just doesn't have the same impact on any recording.

LP: I'll embarrassedly admit that I went down a YouTube rabbit hole of watching various performances of John Zorn ensembles, not even necessarily with him playing. I was in New York for a period of time, and it was a luxury to be able to see him all the time, but these were more performances of him conducting various incarnations of Masada and things like that.

The physicality of the players, whether Joey Baron plays drums with his hands or Marc Ribot just strangles the guitar, if you can sit in a room and watch that and not be excited, then you're cold.

Kevin Sun: Then nothing's gonna reach you because that's the absolute top, the pinnacle of that.

LP: It's so fun because it's also fun to watch the musicians be amazed at what they're doing. At the end of a solo or at the end of an interlude where they're all swinging together, they're laughing. "Yeah, man, you did it. You crossed that bridge."

Kevin Sun: Exactly. It's the joy of discovery. That's something that we live for as artists. If we don't have that, then why go on? It's already so hard to do it.

LP: You mentioned Threadgill earlier on. I wonder if you could talk about both as players and composers who some of your leading lights are.

Kevin Sun: Of course. Henry Threadgill is incredible. In recent years, I have to give it up to Mark Turner, great saxophonist, huge, profound influence on my music and my life. He's incredible.

Vijay Iyer, who was my professor in college and whom I TA'd for, is a really heavy thinker and musician inspiration. There are tons of people. Miles Okazaki is amazing. Steve Lehman. There are all these people, and I feel like I've just ripped off so much of their stuff, and I continue to do it. And I'm sorry, but also the music's so great. I have to do it.

Lately, I've been really into Ryuichi Sakamoto, who passed away last year. Something about it, I don't know; he can work with tonal music and melody, and it can be really simple and just so affecting. Also, his experiments in terms of electronic music can be so exciting and experimental. We've been playing a lot of arrangements of his music over the past year, which has been a lot of fun and a different sort of challenge.

LP: I just watched or re-watched Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, the other night. I forgot he's so powerful as an actor.

Kevin Sun: It's unbelievable. He has an amazing cameo in what I think is a pretty terrible Abel Ferrara movie that I saw recently. It's called the New Rose Hotel. It's a crazy movie because the co-stars are Christopher Walken and Willem Dafoe, but it's kind of terrible. It just kind of goes around in circles, and I feel like they were just doing it for fun. You can tell they're having fun, but the plot is just not happening.

But anyway, Ryuichi Sakamoto is in one scene as a very menacing corporate figure. He says almost nothing. He does everything with his eyes, which, the way he's looking at them, are just lasers.

LP: He does quietly seething very well. It's incredible.

Kevin Sun: "Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence"... this is totally random, but I had COVID for the first time a few months ago. I remember the first day I was really sick. I don't know why I did this. Maybe this was the COVID brain, but I went down a rabbit hole of trying to listen to every cover of that song. And there are like hundreds.

So, I was going through Spotify. It's crazy. There are so many covers. A lot of them are really boring because a lot of them are just people doing a solo piano version that's not as good as the original, but then there are some that are really interesting. I think there was one; I believe it was an Argentinian pianist. I can't remember the name, but it was a duo with percussion, and it was in a different meter. It was in five, and it had added sections and pedal points, and it was really dramatic. It's amazing when you hear that degree of flexibility from the source material; then you know it's a strong song.

LP: It's funny; this is again another embarrassment, but I was similar. I was sick. I was watching covers of John Cage's 4'33" on YouTube. There's a funny one. There's a death metal one, a death metal band. And as ridiculous as it sounds, it's incredible to watch.

Kevin Sun: It's like in the middle of one of their concerts or something?

LP: No, no. It's in their rehearsal space. It's incredible. There's nothing campy about it. It's incredible.

Kevin Sun: I gotta look it up.

LP: Yeah, there are some great ones on YouTube. Some are tongue-in-cheek, but some are amazing. There's a harpist who does a cover. YouTube is an amazing place for music.

Kevin Sun: Oh, it's incredible for music.

LP: I'm curious if Lowlands is suitable for recording. Would you ever record there? Would you record a live album there?

Kevin Sun: It's funny you ask. Maybe you don't know, but I'm putting out a record that was recorded there in three months. (laughter) Sorry, I didn't know if you were setting me up for that, but I'm literally preparing materials for it.

Yeah, so we did record my trio in June of 2022. This is basically the first year of my time there. And so that's coming out in March, and I think it came. It was sort of a last-minute thing. We recorded it using my laptop; eight microphones plugged out really well into an interface plugged into my laptop.

A really good friend of mine, Juan Montrujillo, who's a great guitarist and also a great engineer, helped. It sounds good. The room sounds really good. I think we'll probably record there more in the future, but it's surprisingly good.

That's one thing that we discovered because it's all reflective surfaces, like wood floors and brick walls. You wouldn't think that it would sound good. You'd think that it would be really echoey, but somehow the layout of the room - it's long, and where we put the band is at the very end of the bar facing toward the front, and there's a little alcove because of where the bathroom is—some of the sounds reflect to the band. It makes the space a little smaller, so it actually sounds really nice.

Especially if you go farther away from the band, it's mixed really perfectly. For example, if I sometimes see a show and I just want to hear what's happening really clearly, I can sit at the very back of the bar, and I can hear every instrument really clearly. However, if you sit close to the front, you get the full impact.

LP: That's interesting. Was it in front of an audience, or was it just you guys?

Kevin Sun: It's a live recording, but it was close-mic'd as well. I think it's the best of both worlds. You get some audience vibe. The way we were playing was definitely the way we normally play in front of an audience, and there were more people than normal because I just invited a lot of people because I knew that I wanted ideally to have it be fuller just for the vibe.

LP: That's incredible. I can't wait to hear it. What's the configuration?

Kevin Sun: It's myself on saxophone, Walter Stinson on bass, and Matt Honor on drums. This is a band that I formed when I first moved to New York. We had already put out two records, toured China and the East Coast, and had all this music that I had written over the years. I just wanted to get it down.

We worked really hard at it before. It's sort of my dream of having this working band where we don't look at any music. All the music was memorized, and we didn't have a list. Basically, I would just start playing, and then they would play, and then I would do a subtle signal, imperceptible to the audience, of a song. This is another thing I took from Vijay because he would do this.

Then I would musically signal that we're going to go into something, and then we go into it, and all of a sudden, it's like, whoa, how did you get there? After the song ends, we would just keep playing and be in a vibe. And then whatever popped in felt appropriate, so we could go into that.

So it's an amazing feeling because you just play the whole set. You don't say a word. You don't have to open your eyes unless you want to see the audience, but you don't have to look at any music. For me, that's like a dream musical experience.

LP: And continuing a long line of the saxophone trio, which is a great lineage.

Kevin Sun: Just trying to contribute in some way, trying to uphold that incredible tradition.

LP: Do you think that modality of what you just described, that performance style, could you do that with a larger ensemble? Is there something exciting about the idea of maybe a septet that you conduct that way?

Kevin Sun: Oh, man. If you have the willpower, and the musicians are down, and you can rehearse, anything can be done. Famously, Cecil Taylor's big band taught each musician every part by ear. So the rehearsals were full days, 12-hour days. Then you don't need sheet music; you can just go into it and hit, and people know what's up. But that's a lot of work. You just have to put in the hours.

LP: I would imagine at the end of that, just because of the mental concentration, it's got to be tiring.

Kevin Sun: It's exhausting, but I don't know. Reading music is tiring, I think. Also, there's something about the sound of musicians remembering how a song goes.

Everyone remembers a little differently if you haven't played it in a while. When you get together, and you're playing a song that you've played a lot, different parts come back to different people in different ways. It's like people are retelling a story that they know, but they're helping fill in the gaps for each other. It comes out a little differently every time. There's something about it that I find beautiful as opposed to, "We are rehearsing this. We're telling the story word for word the same way because we're reading the music, so it's right there."

LP: That is beautiful. That's really beautiful. And you also hit those moments where everybody remembers at the right time. We're back in the swing of it, and then it hits.

Kevin Sun: Ideally. That's what's supposed to happen.

LP: Kevin, thank you so much for your time.

Kevin Sun: Oh, thank you. It's a pleasure. Super fun conversation.

Are you enjoyng our work?

If so, please support our focus on independent artists, thinkers and creators.

Here's how:

If financial support is not right for you, please continue to enjoy our work and

sign up for free updates.

Comments