Among a traditional orchestra, percussionists might as well perform in isolation. The audience sees them obscured beyond a forest of music stands, often accenting rather than driving the composition. Percussion's evolution in modern music feels more overdue than a shake-up. Players now often shine at the forefront, and innovative musicians like Lisa Pegher are welcome to dismantle invisible barriers between rhythm keeper and audience, between physical gesture and digital response.

Percussionist Lisa Pegher has built her career on expanding the boundaries of classical music through technology and innovation. From her early training as an orchestral percussionist to her current role as both lead performer and software engineer, she represents a new generation of musicians who move fluidly between traditional concert halls and digital laboratories.

Throughout her career, Pegher has commissioned and premiered numerous works that have brought percussion instruments to the forefront of orchestral performance. Her collaborations span traditional classical venues to electronic music festivals, including recent performances at Manhattan's Perelman Performing Arts Center and the DiMenna Center for Classical Music. As a soloist, she has appeared with major orchestras worldwide, from the Boston Modern Orchestra Project to the Thailand Philharmonic, consistently pushing the boundaries of what audiences expect from percussion performance.

Her latest project, A.I.RE (Artificial Intelligence Rhythm Evolution), showcases this visionary approach. Working with the ICEBERG Composers Collective, Pegher has created a multimedia concert that traces the evolution of percussion from acoustic instruments to AI-generated compositions. The performance incorporates traditional percussion instruments alongside digital interfaces and custom software, demonstrating how modern technology can expand the possibilities of musical expression while raising questions about the future relationship between human performers and artificial intelligence.

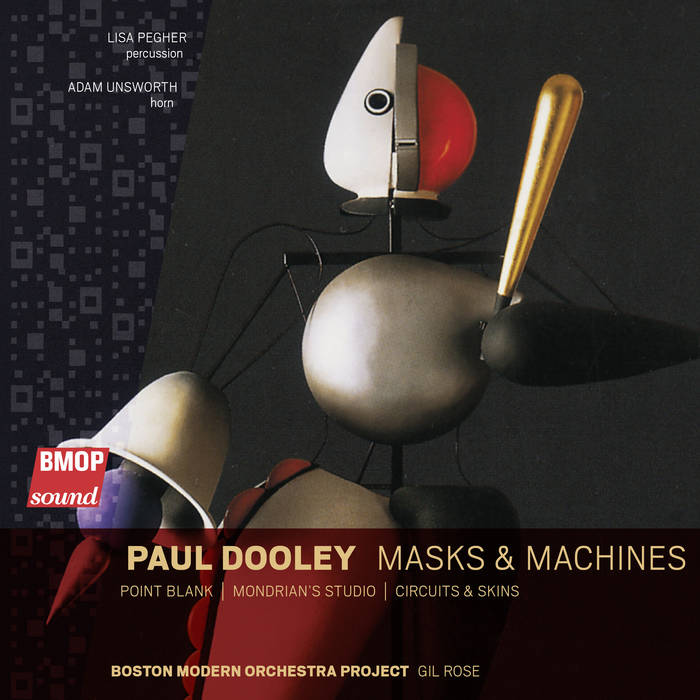

On a recent episode of the Spotlight On podcast, host Lawrence Peryer discussed the A.I.RE project with Pegher, her Circuits & Skins collaboration with composer Paul Dooley, and the roots of her technology-fueled curiosity about the possibilities of the percussive craft. Listen to the entire conversation in the audio player or read the interview below, edited for length and clarity.

Passing Through the Gates

Lawrence Peryer: I want to start a little bit at the beginning. Could you talk about your early relationship with percussion and what drew you to that particular expression?

Lisa Pegher: I always tell people that percussion chose me when they ask that question. If I had to pinpoint how I got into it, somebody handed me a pair of sticks one day, and those sticks just ended up becoming part of me. I don't remember who it was—maybe a family friend who handed the little kid a pair of sticks at a party. But I felt like I had already known how to use them and just started playing around.

It wasn't necessarily an immediate "Oh, I think I'm going to be a drummer," but I was always drawn to playing with the sticks. I started playing wherever I could. Eventually, when I got into grade school and was exposed to different types of instruments, the teacher saw that I had some talent and encouraged me to play percussion. Since then, I just started practicing a lot, knowing that was what I wanted to do.

Lawrence: Did you have a typical drum education? Did you work on grip and all that stuff?

Lisa: Yes, I was fortunate to have a very good teacher who emphasized the importance of good technique. It was very much like The Karate Kid in that you had to pass one phase to get to the next. It was a very disciplined practice, and the teacher taught his students the same way. It didn't matter who you were—you had to pass these different gates to get to the next phase.

It was an everyday practice type of teaching, which I'm very grateful for, versus some people who bounce from teacher to teacher and maybe pick up different techniques but don't have anything solid to grasp. That core teaching lent itself to everything else in life. Looking back on it, I realize you could say that about anything you're learning—focusing on how to do the essence of the thing first can make everything else much easier.

Lawrence: How long did your formal training or formal studies last?

Lisa: I like to say I'm a forever student—I never stop learning. There are always more things to learn. Also, what is formal? Formal might mean something as simple as when you stop studying with a mentor.

Lawrence: At what point did you have the desire to bring percussion to the front of the stage and reconceptualize the role of percussion in your performance?

Lisa: I've always felt, from the first time that I started playing the drums, that they were like melodic instruments. It was just natural for me to hear and play drums that way. When I got exposed to different types and genres of music, I realized there's the opposite mindset: people consider drums to be just playing as loud and fast as you can—that's how you're determined to be good or not. I would rather compare myself to the violinist than to somebody trying to see how fast and loud they can play.

I got into one of the area's youth symphonies and realized, "Wow, there are soloists who play in front of the stage, these concertos and things, but most of them are violinists or pianists." Why can't we have percussionists standing up there and playing all the percussion instruments beautifully and melodically like these other soloists playing concertos? That's when I had the shift of thinking maybe this is somewhere where I could make an impact and start to bring percussion to the front of the stage.

Most concerto competitions didn't allow percussionists to join. I had almost to beg and plead for them to hear a percussionist. I had to get some of my piano friends to write piano transcriptions of these concertos to take them to some of these competitions early on. It was an uphill battle even to get presented in that way.

It didn't matter to me within that time frame because ignorance is bliss. I knew what I heard in my head and what I wanted to do then, so I strived for my dreams and goals. But then I also realized that maybe there are other avenues for this. That's when I started creating my own recital-type shows to take into places.

A Different Set of Paints

Lawrence: When did electronics and technology enter your practice?

Lisa: Holding on to any one thing can hold an artist back, and I realized that the classical music industry wasn't the only place for me. During this time, electronics were creeping even more into music and arts. As a drummer who wants to create soundscapes, I'm looking at percussion as a different timbre, a different type of music, and a different set of paints that I can add to my palette. I'm thinking, how can I get this technology integrated into what I'm doing?

So, I started exploring different types of software and other programs that allowed me to sample my drum sounds, manipulate them, and then trigger them live in my performances. I was also reaching out to other composers at the time and saying, "Hey, instead of this traditional stuff that a lot of people are writing, can you write me something that mixes electronics with acoustic percussion?"

That made things very interesting. I started exploring these different software programs, which led me to software engineering and programming. There, I began to dig into the code and figure out how these things work under the hood. This took me into another realm, like building programs that create music itself.

Lawrence: Please tell us about your A.I.RE project.

Lisa: The ICEBERG Composers Collective from New York City had reached out and proposed having their composers write pieces for me. I immediately had an idea: Why don't we do something focused on AI and mixing electronics, taking whatever we currently have in the music industry? My task was for each composer to make a piece that evolved from my love of technology, music, and percussion.

Eight composers created a timeline of analog sounds, mixing electronics with percussion and then just electronics—percussion as electronics, not acoustic or analog. Then, we came to integrate artificial intelligence where we are today.

The show takes us through that journey. There's a visual aspect to it, too, where I have a live touch designer who takes some of those ideas and does a VJ set of the animation with it. Then, towards the end, my human figure turns into the image on the screen, and my motions trigger the music. Eventually, the computer is just playing things from what it learned from me throughout the show.

Lawrence: How have rapid changes in AI technology changed the A.I.RE performances since its inception?

Lisa: The output is getting much easier to listen to, has better results, is more of what you would expect, and is less digital-sounding. The interactive things you can set up, the tools, the software where you control what's happening by motions, motion detectors, and connecting visual software with the music inputs, too—all of those integrations are getting easier to use.

If I started over tomorrow and said, "We're going to put on the A.I.RE show, except the guidelines now are that we're not using any of the same technology. We're only using what was created from 2022 onwards," we would have different results. It would probably have a different vision and feel.

Lawrence: Could you talk a little bit about Circuits and Skins? As a listener, I perceived a sense of narrative, much like what you talked about with A.I.RE.

Lisa: I went to [composer] Paul Dooley and said, "Hey, I want a concerto with electronics and percussion. I want to bring percussion to the front of the stage. But I also want to get new types of audiences and different kinds of people into classical orchestra halls." That has always been one of my big passions. It doesn't just have to be classical; it can be classical and modern. It can be concertos like Circuits and Skins.

Paul had gone to an EDM festival called Northern Nights and was writing from the perspective of his journey there. When he brought the composition to me, Paul opened the palette and said, "Lisa, most of the music in there is improv." A lot of the stuff I'm playing is long sections of music where I have the artistic freedom to improvise and decide what will be in that concerto.

And so whether or not this dream of ours takes off how I wanted it to is not really up to me. It's fate and how life evolves and manifests, but that is the journey. One of my favorite writers is Thich Nhat Hanh, who wrote a book called The Art of Power, which talks about how power doesn't come from any of the obvious things in our society. It just comes from being human, that life is happening, and we are just beings in it and being able to accept those things as part of really coming into true power.

Lawrence: This makes me wonder how Mahler was perceived 125 years ago, or more broadly, when atonality started to creep into classical music and how audiences were either incredibly alienated or outraged by it. Still, some audiences were completely enraptured and excited by it.

Lisa: There was a time when a premiere would happen in the classical concert halls, and people would show up because that was an exciting thing to do. That's what I'm striving for. Our culture is still doing that, but they're doing it at things like festivals and EDM shows.

I want to see if we could reverse it and ask why we're shutting people out of some of these other avenues today. Is it because they're not accessible in the same way that these festivals are? So, we must break down the barriers on both sides. Take something like this to South by Southwest. Take something like this to any Masterwork series at these classical music concerts. It's all about reaching into the different people who want and are hungry for it and will be positively inspired and affected by it whenever it's put in front of them.

I like to say, and it's true, that oftentimes, people don't know what they want until you show it to them. We're not showing it to them, and we're not even open to putting out something different and showing it to them. How are we going to know if it's something that people want? And that's where I wake up every day and choose to keep trying.

Purchase Paul Dooley: Masks and Machines (feat. Lisa Pegher) from Bandcamp or Qobuz and listen on your streaming platform of choice. Check out A.I.RE at aireproject.xyz. Visit Lisa Pegher at www.lisapegher.com and follow her on Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments