Lloyd Barnes' journey, as related by Niko Koppel in his 2009 New York Times piece on the reggae titan, is a long and winding one. Born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1945, Barnes grew up in the heart of Trenchtown, a tough neighborhood that was also a crucible of so much of the musical creativity on the island. From an early age, he was drawn to the sounds of ska and rocksteady, and he befriended future reggae luminaries like Bob Marley and Bunny Wailer. He haunted Studio One, where not only Marley, but also reggae giants like Toots & The Maytals cut classic sides. "I found a certain peace in the music," Barnes told Koppel. "It's not always good times, but the music gives you that."

Barnes first arrived in early-1970s Brooklyn amid a groundswell of Caribbean arrivals. He worked day jobs but lived for music, hustling DJ gigs, hauling his turntables and records. When he put down roots in the Bronx, he poured his earnings into a studio, first in a basement, then in storefronts on White Plains Road. Wackie's was born (from his own nickname, "Bullwackie").

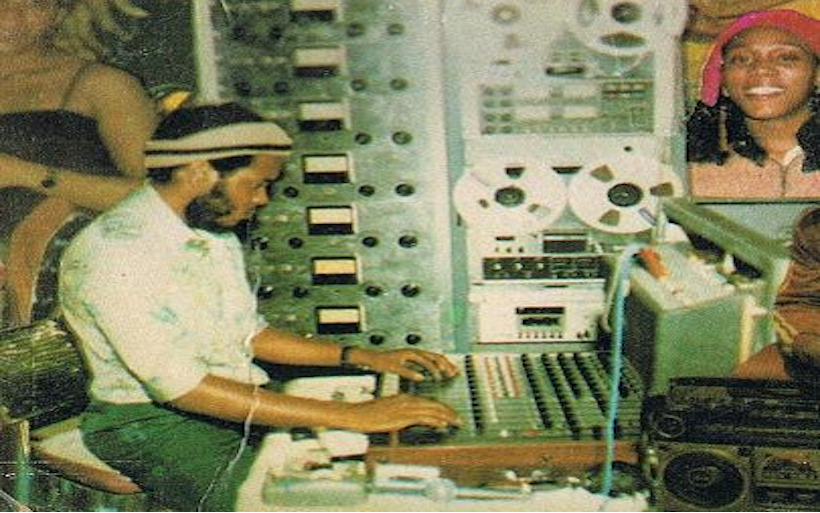

Barnes built a sound and a scene, one that hit far beyond the Bronx. As Koppel wrote, Barnes "perfected his raw analog sound, defined by deep drum, bass, minimal lyrics and interludes of reverb." He recorded now-classic tracks by Jamaican luminaries like Sugar Minott and Wayne Jarrett, releasing short runs on his own label marked by a distinctive lion logo. One collaborator, Milton Henry, told Koppel, "It was a New York sound...It had a whole different energy".

But Wackie's was more than a sound; it was a vibe, a pocket of Jamaican warmth in the big city. "It was like the reggae Motown in the Bronx," recalled percussionist Ras Menelik DaCosta. "People get wives just from being there; some people became fathers. It took on a life of its own". Claudette Brown of the duo Natti Love Joys told Koppel: "Those were good times, I miss those years. But this is it, this is where I belong".

Despite the vibrant community around Wackie's, Barnes struggled to stay afloat. Lacking major-label distribution, he could only press records in small batches, and sometimes went without basic utilities. "It was difficult, but we were doing what we wanted to do," he recounted to Koppel.

After 13 years, rising rents shuttered the White Plains Road studio in 1989. Barnes decamped to New Jersey for a season, while the Wackie's legend only grew, fueled by collectors and reissue labels. By the dawn of the 21st century, "Wackie hit his heyday," as one NYC record-store owner told Koppel.

In 2009, Koppel found Barnes, 64 and based in a new Bronx studio he built himself inside a record shop on 225th Street. The music business had transformed in the digital age, but Wackie's endured. Old hands like Brown still congregated to cut tracks and bask in Barnes' presence. "If you have music in you, he's going to bring it out," longtime collaborator Lenny Chambers told Koppel.

Barnes is now approaching 80 and Wackie's still generates analog warmth in a hyper-digital world. The Bronx around it has morphed and gentrified and many of the veteran artists are gone, but by all accounts, Barnes still serves the music from behind his beloved mixing board in the space he built by hand.

Barnes told Koppel back in 2009, referring to the journeys of his 500-copy pressings, "When I travel, my records pop up everywhere; sometime I wonder, how come 500 records can get this far around the world?"

Comments