In 2018, Mauricio Moquillaza transformed an abandoned house in Lima into a venue for experimental music performances. His initial search for performance spaces grew into Deshumanización, a vital platform for Peru's new generation of sonic explorers. Through this collective and its recently opened cultural space, N!, Moquillaza has connected sound artists, visual creators, and performers, cultivating a vibrant ecosystem for experimental art in Peru's capital.

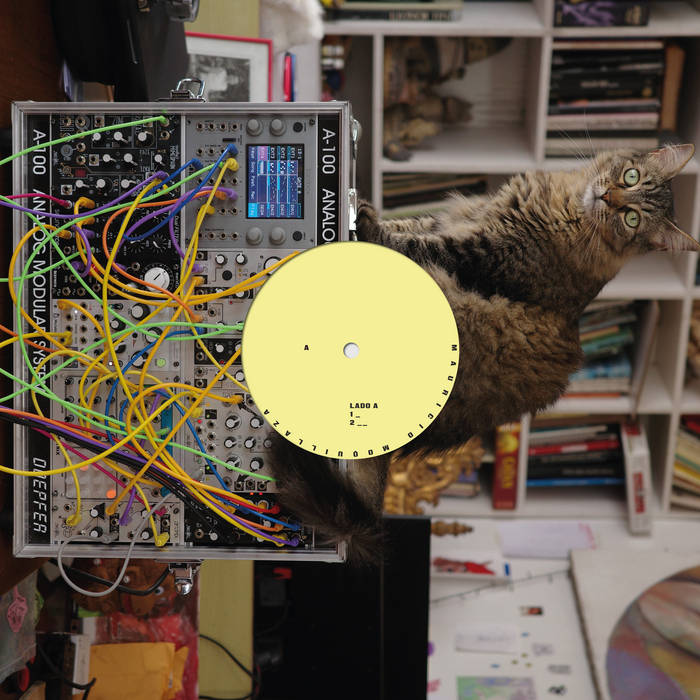

Moquillaza's self-titled debut album on Buh Records presents four pieces that showcase his distinctive approach to modular synthesis. While recorded in single takes without overdubs, these compositions balance precise sequencing with improvisational spontaneity, reflecting his background in free improvisation and noise music. The limited vinyl edition of 300 copies emerges as more Lima artists embrace hardware synthesis and analog sound creation, expanding the possibilities of electronic music.

Lawrence Peryer: Could you describe the musical landscape in Lima when you started Deshumanización in 2018? What gaps or needs did you see that motivated you to create this platform?

Mauricio Moquillaza: There were limited performance spaces when I started to get involved in the experimental music and free improvisation scene. I only knew of Casa Suma in La Victoria, run by my friends Kike and Chicho, in addition to events by Buh Records. I felt it was necessary to have a platform where projects of this nature could develop sustainably.

Having space available in an uninhabited house, I decided, along with Árbol (Diego Faucheux) and Subcutáneo (Marcelo Mellado), to form a collective that would not only promote performances but also serve as a seedbed for new proposals, creating a place for discussion and listening for all those interested in these arts. I met both of them while seeking free improvisation collaborators. With Árbol, it began because I had an Organelle, and I knew he was making electronic music, so I thought it would pair well with my musical practice at that time—that was how Paundra was born. With Marcelo, it was simply through improvising. Promoting and organizing were all trial and error; we learned through making.

This type of music is seen as alien when, for me, it is part of sound creation. This perception has changed thanks to the internet and unconventional elements in more mainstream music, like noise. I see people now much more open to listening to bolder proposals. Our main need has always been to express ourselves in our way, be as free as possible, and generate things without being tied to any specific trend or language. We were a mass of people looking for this to be the center of our practice—that intuitive, almost feral, and even spiritual thing that allowed us to immerse ourselves in the sound spectrum. It was like a laboratory in which anyone who wanted could participate.

Lawrence: As someone who produces events and runs a collective, what changes have you observed in Lima's experimental music community since you began performing?

Mauricio: The most significant change is the articulation of collectives. Over the years, we have formed important alliances with friends and colleagues among spaces like Paradero Cultural, Casa Bagre, Proyecto Amil, and others. These are crucial in developing these expressions, and their organizers have always been willing to provide whatever support they can. There has also been a substantial evolution in the quality of productions; recently, all the local projects seem to have a high standard of performance and commitment. There has been a sustained consistency, and I feel the Lima scene has a distinctive sound.

Lawrence: The tracks on your album were recorded in single takes without overdubs. What draws you to this approach? How does it connect to your background in free improvisation?

Mauricio: My approach to the instrument has always been improvisation. Many years ago, at a concert by a musician I admire, I asked how he approached his practice. He simply said, "Press the record button and start playing." So, what I did was design patches, and if I liked the dynamics of a patch, I just hit record and played everything I could. Free improvisation is part of my artistic philosophy; it's strange because people confuse being an improviser with being haphazard. It's never just throwing yourself into the void of the unknown; it's going into the unknown knowing one can create various routes over time, creating narratives and generating interesting contexts.

Free improvisation incorporates known and internalized resources to express, or rather reflect, the moment that is happening, entering a fluid state and being a reflection of that moment—but in sound. What attracts me most about this approach is that I can relive how I felt when I listened to what I played. I'm drawn to its organic nature; I find beauty in something unrepeatable. You enter a trance, and sometimes things just happen. I'll probably never play those pieces the same way again, and I find that beautiful, too.

Lawrence: The equipment you used to make this record was important enough to you to list the hardware in the credits. What attracted you to modular synthesis? What feelings do you have about the hardware?

Mauricio: In 2018, I only played with prepared instruments, pedals, and objects; I was quite unfamiliar with electronic music. My interest in hardware came from a good friend, Viviano Wich, who arrived from Austria in 2019 and attended a free improvisation concert in our space. We became good friends and shared many moments beyond music. He had a modular synthesizer, which seemed like the strangest thing in the world. I didn't understand it, but I listened to how it sounded and found it marvelous. Then, I began to listen to synthesizer music, starting with classics like Laurie Spiegel's The Expanding Universe (which is still one of my favorites), Morton Subotnick, and later became obsessed with Keith Fullerton Whitman and his generators, Caterina Barbieri and her work (for me, the best of all), Patterns of Consciousness, etc. I found infinite malleability combined with the fact that I could control everything, having an ensemble of many voices under my control without relying on anyone else. With synthesis, everything was under my control: my decisions of form and aesthetics.

I'm not a hardware fetishist. I don't venerate iconic synths nor try to emulate the sound of other synthesists. I'm not very technical or orthodox in my patching styles or how I arrange my modules. The choice of my hardware was mostly functional. I'd see them in YouTube videos, and if I thought I could use them creatively or that they could add to my practices, I would try to acquire them.

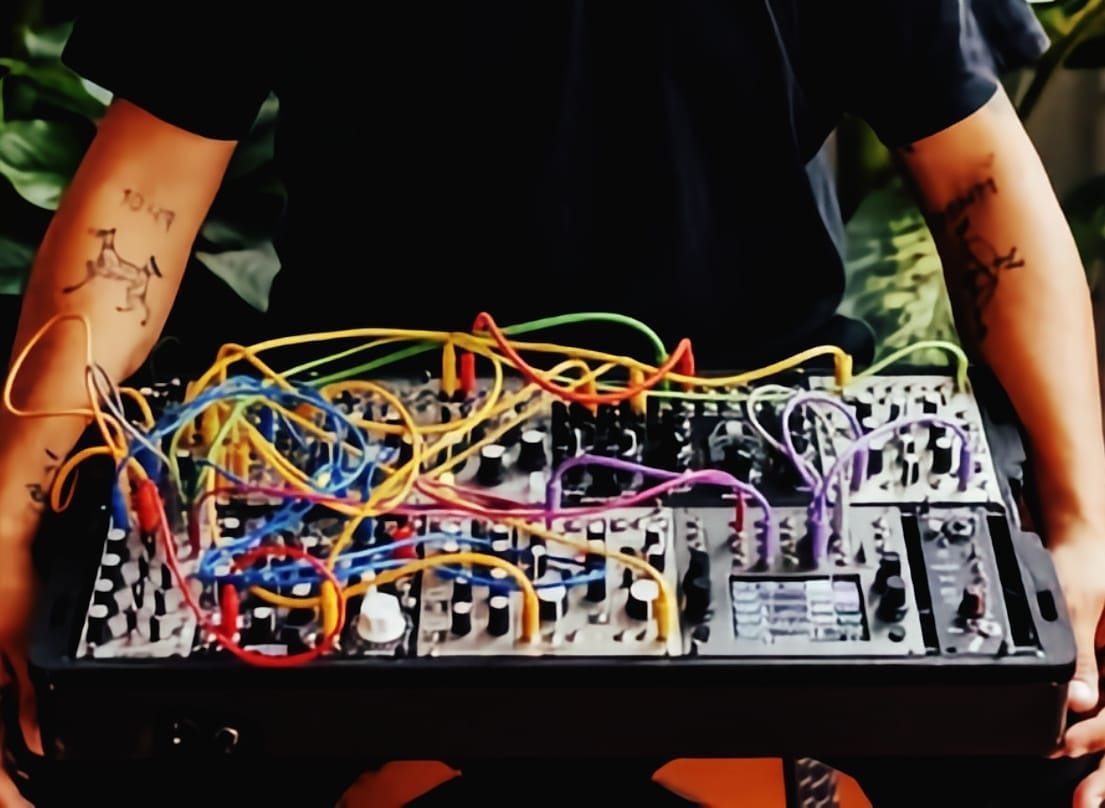

I play the synthesizer as I would any instrument, like an extension of my body. I don't like patches that somehow play themselves. Still, I do enjoy creating situations where the ecstasy of the moment leads me to do certain things intuitively that result in something unexpected. I like entering an almost altered state when I play, and I also experience this when I play the electric bass in improvisation ensembles. It's what I seek—those nearly religious experiences of simply being there, being sound.

Lawrence: The press materials mention "tension between control of the instrument and its generative possibilities." Could you explain how this dynamic plays out in one of your pieces?

Mauricio: Because there's also a dose of design in the patch, the control comes from the primary sequences I compose and the instrument's design. This album is mainly made from a couple of sequences for each track. Then, it is modulated to make it seem that much more is happening; how each module relates to the others is the key to making this happen. The instrument would sometimes basically play itself in strange ways. In these moments, I just like to contemplate and listen; it's as if it brings forth its voice and creates a new and unexpected context.

Lawrence: The project #ffffff combines analog and digital image generation with sound. What interests you about the intersection of visual and sonic arts?

Mauricio: Different visual artists I met were interested in experimenting with sound creation, and I saw the possibility of creating a complete sensory experience. As we experimented, I realized it was possible to develop a collective language that could express the same thing I aim to express with improvisation but from another medium.

Working in interdisciplinary contexts enriches my practice by providing new routes to understanding expression. For example, now that I've been working with people dedicated to dance or movement, I feel that bodily dynamics can resemble how one plays. After all, one plays with the whole body, following different rhythms, inflections, and gestures. You learn to read the performers, and that's the most incredible aspect of these collaborations. It's more controlled in theater since, even though it involves some live improv, I need to read or anticipate moments. I think the most enriching part is that the particularities of each art form merge; it's like fusing idiosyncrasies. This experience affects how I operate in a solo format. One absorbs all these experiences and eventually expresses them in their artistic work, so it's an unconscious process.

Lawrence: Could you tell us about some local artists and developers who influenced your approach to electronic music?

Mauricio: Well, in Lima, I have many influences; some of the most important have been my improviser colleagues, such as Camilo Ángeles, a flutist with whom I studied for a time; Tete Leguía, a bassist who inspired me during my time with Paundra to prepare my instruments with objects; Árbol, who gave me a new vision of sound creation while collaborating in Paundra with the electronic aspect—this might have been my first approach to electronics, even though I was doing improv with a bass and objects. Then there's Paruro, with his noise and minimalist setups and layer constructions of noise, which are an important part of my influence. There are many others, including Oscar Recarte and his textural control; Abel Castro and his limitless noise; Necrosante and his abrasive sequential techno; Habo with his infinite rhythms; Marcelo Mellado with his celestial ambient sounds; and Industrias del Terror with their frenetic rhythms. A new wave of younger artists has also significantly influenced my perception of sound creation, especially Haiti Bon Aire and Drugstorecoreboy (a.k.a. Vini/Mentalidad).

Lawrence: Your recent tour in Chile marked an international expansion of your work. How do audiences outside Peru respond to your music, and what have you learned from these experiences?

Mauricio: For this trip, I was touring with my colleague Sebastián Suárez, who plays live visuals. A few months before the tour, I started incorporating an electric charango processed through the synthesizer. I wanted a traditional instrument to create counterpoints or contradict what happened in Eurorack, creating a new, sometimes uncomfortable context. It was very rewarding; we had several gigs, but each one was quite different from the others, and in each, I discovered new elements—it was a real trial and error process. As for the audience, I think we were very well received. These genres tend to be niche, but the scene that welcomed us was committed to this work. I also met some special people through their projects. Among them, Lautaro de las Casas completely blew my mind with his set, Thanatoloop with his sampler work, and Armando Saragoni with the best ambient set I've seen in my life, along with my colleagues from Valparaíso, like César Bernal and his mastery of extended double bass techniques.

Lawrence: What role do you see Deshumanización playing in nurturing Lima's next wave of experimental artists?

Mauricio: Deshumanización has been playing a role for years as a platform for project development, besides being a seedbed and a space for experimentation and education. We're committed to encouraging people to experiment with sound and art. Lately, we have collaborated more with new collectives and working with an exciting new generation. Some barriers have been broken regarding how people perceive more experimental music. Our last event, "No Nunca," brought together seventeen projects, including experimental rock, shoegaze, noise, dream pop, sound experimentation, and similar things. I believe this marks a turning point in my work and is also the result of years of work as a promoter in Deshumanización; many of the projects were those we helped on their sonic journeys. Now, with the new opening of our cultural space, N! Espacio, we will generate more projects, residences, and art exhibitions. It's a very good moment for Lima's alternative scene; many things are happening, and it's an exciting time.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments