(This transcript has been edited for clarity.)

LP: Thank you so much for making time to talk today.

Nic: Pleasure.

LP: Really excited for this. In doing my prep work and reading about Comateens and the various incarnations over the years. Obviously, it's a fascinating time just in New York and music and the arts.

Nic: That's for sure.

LP: I used to perceive them as different worlds, right? There was the downtown CBGB scene, there was what Philip Glass was doing, and there was whatever was going on in the jazz world. And I've really come to understand through various readings over the last year or two that there was much more cross-pollination and overlap than I think the previous histories really indicated.

Nic: True. I think one thing we were not was punk, which seems to be the sobriquet applied across the board to everyone working in those days and in those places. But really, punk was a very narrow thing, and we were not it.

LP: What were you at the time? I think history has called you something else, but what were you at the time?

Nic: I don't want to delve too deeply into what history might have called us. I think we would be termed New Wave, maybe? I don't know. We were younger than a lot of the groups doing CBGBs and Max's and all those places. So we were at the tail end, Talking Heads, and all those bands were older than us.

We were one of the first groups on the scene to use electronic drums, for example. It was us, there was Suicide, and across the pond, there was Kraftwerk. We were known as an electro-pop band. Our sound was unique, really.

LP: Talk to me a little bit about Pre-Comateens Nic in terms of what music world you came out of or what you grew up listening to because it's not immediately obvious.

I hear some of the '60s pop references.

Nic: Oh, yeah.

LP: But I'm curious as to what was in your head at that point.

Nic: I was born in London, England, and raised in Manhattan. My parents loved folk music, so there was always a lot of folk music on the box. My parents were the first people I ever knew who owned a Bob Dylan record, for example.

And then I had classical piano, and then a janitor in a building was a jazz drummer, and he taught me some jazz drumming kind of stuff. My first thing was classical music, and then when the Beatles hit, that whole thing changed for me. I thought, "That's a good job. I'll do that."

And I was obsessed with that from then on, and I still am, as a matter of fact. So, I wanted to write pop hooks. That was my big thing. I'm into Gershwin, I'm into TV jingles, I'm into TV show theme songs. I want to write stuff that people can't get out of their heads. And that has been my entire musical drive, my entire musical life.

I'm sorry that Ramona Jan is not with us because she will tell you that she has no influences whatsoever. Her thing was to express herself only, and she listened to nothing. But I'm the one who listened to a billion things—James Brown, you name it. I loved it all, and it all goes into what I do.

LP: It's really fascinating to hear because I've read some of the other interviews that the two of you have been doing over the last few months around this reissue; that point comes up repeatedly that she was a bit of a blank slate in terms of musical influences.

Nic: This is something I never realized about her until these interviews.

I didn't know that. I thought, oh, she's a musician. She must have listened to a million things. Nothing. And she was also an engineer in a major recording studio. She was not impressed.

LP: Let me come back to that in just one moment because there was something you said in your previous response that I just wanted to call out, which is you mentioned TV jingles.

Oddly enough, and apropos of nothing, I woke up this morning with the theme from The Odd Couple stuck in my head. I've been walking around with that all morning. (laughter)

Nic: One of the greatest TV shows ever in history.

LP: And incredible theme song, oh my god.

Nic: Oh my goodness, that is one of the greatest theme songs ever.

LP: It's funny how those things work.

The point about Ramona and what you did and didn't know was also interesting because it feels like that came up a lot in the interviews with the two of you: She didn't know it was your first time singing. You didn't necessarily know how serious and ambitious she was thinking about Comateens.

Like, how did you have so much unspoken between you?

Nic: We were working in the same place, in this recording studio, and we decided to start this band as a hobby. It was the late 1970s. I had already been in multiple bands—a blues band and a jazz band—and we just thought we would do it as a lark. We started in a tiny little room in Ramona's apartment with a bass guitar, a guitar, and a rhythm box.

I had no idea that she was aiming for a music career. I thought we were fooling around. But it went further than that. I'd had plenty of experience; I'd already played in the New York clubs, and she was learning certain things from me. I was learning a lot from her because she was primitive in many ways, and I thought that was great.

I just loved starting from ground zero with no influences and no preconceived notions of what we should be doing. I really liked that. It took this project 40 years for me to understand a lot about her.

LP: It shed a lot of light on potential explanations as to how you stopped working together, right? If one person has more, I don't want to say seriousness but has a different sense of what the outcome should be than the other, that right there is, that's built-in tension.

Nic: No, that was not a tension between us at all. The reason we stopped working together was that my brother was having a lot of problems, and I wanted to bring him into the band as our guitar player to give him a focus, to give him something to do. And since I didn't think that we were doing it seriously as a career, I thought, okay, we're just going to do that.

I could have done it better. David Byrne is out there now telling everyone that he handled the breakup of the Talking Heads very badly. And now he's trying to fix it with the other guys. But we were young, and we were in our early twenties. I said, Oh, okay, I'll have my brother in the band now. That'll give him something to do, and that's what happened.

That's why we stopped working together.

LP: It's something to see in the dynamic between the two of you. I struggle for the right adjective, but there seems to be so much admiration and respect for each other. You both got a lot from it.

Nic: I love Ramona deeply. What we did together in the three years that we worked together. It was very powerful for me and has remained with me since then, since 1977, 78. She's an incredibly talented artist.

We just drifted apart, and I went off and did other bands, but the effect she had on me was very powerful—and remains so.

LP: To zoom out a little bit, could we revisit this concept of the other things that were going on in New York? Were you cognizant of being part of any scene? Who were your contemporaries? If you were younger than some of the other acts, who were you looking towards as your generation?

Nic: The thing about that scene is that everyone was completely insular and in their little bubble in the universe, and nobody looked to anybody. Everyone was struggling to be the most singular and unique thing that ever hit the boards. I guess Suicide. I don't remember looking towards any of the other groups for inspiration or companionship.

LP: Wow. That strikes me as maybe being a bit of a New York thing in terms of everybody grinding it out, right? To an extent, there's some zero-sum-ness to it.

Nic: Grinding it out is a great way to put it. Being a rock musician is like being a construction worker. It's physically incredibly demanding. You're hauling incredibly heavy equipment at 4:30 in the morning, and it's cold, and yeah, it's a rough life.

You meet people along the way who you like and some you don't like. I must say that in those days, there was a huge amount of drugs, just drugs and drugs, and drugs, and people were just half awake all the time and half sane all the time. People died, and there was heroin, and it was nasty.

I worked with James Chance a lot, and he's not a person you can communicate with. He was an incredible musician and a fascinating personality, but he was completely in his own world. And that's what that scene was like. Everyone was in their own world.

LP: When I was listening to the post-Ramona compilation, a few things struck me. Even in the earliest singles, first of all, the sound quality of the recordings lends so much to their timelessness. Those records do not sound like low-budget, independent projects.

Nic: Well, thank you very much. Can you be more specific about what you're referring to?

LP: Obviously, the reissued singles that prompted this conversation, but then there's a compilation on Spotify that spans, everything from—I forget the exact year range in the title.

Nic: All of those tracks, as well as the two singles we're discussing, were made under a major label contract and in major studios. The recording engineer for those records was Harvey Jay Goldberg, who's now the audio engineer for Steve Colbert on 'The Late Show.' He was a terrific engineer, and we were very lucky to have him because many recordings from other bands at the time didn't represent how they actually sounded.

LP: My earlier question about your contemporaries—some of the things I was hearing reminded me most of what Anton Fier and Bill Laswell were doing, like with Material, even though your use of the drum machine predates them. It was similar in terms of blending indie rock, electro, and a fascinating stew of technology, organics, pop, and experimentalism. It was such a special mix where people didn't feel constrained by genre.

Nic: The original reason for using the drum machine was much more mundane. We used it because it was the only way we could fit ourselves and our equipment into a taxi to go to a show. We thought, "Oh, this is great. We don't have a drummer, so we don't need a van. We don't need to pay anyone to drive us. We have an eight-inch box that'll be our drums." And that was it. There was no other reason.

LP: Again, New York is the mother of invention. (laughter)

Nic: It put out a beat. It forced us to play very precisely, which was a good thing because it's basically a metronome, but there was no artistic impetus or deep thought behind it.

LP: It's interesting. You talk about the precision and metronomic nature of it, which opens up the possibility of being played in clubs, right? It becomes dance music, DJ music, whether that was in your mind or not. Just that application of technology opens up that world for you.

Nic: Absolutely. Our very first recordings with Ramona, even before the ones you heard, were very rhythm-box-heavy. They immediately went on the jukebox in Max's Kansas City. People played them a lot. I think that's one of the reasons. They were very clear, precise, and enjoyable recordings.

LP: If you had initially gotten into this project without thinking about it in terms of ambition or as becoming the thing, what shifted for you? Was it just responding to the reaction you were getting and saying, "Hey, there's something here, let's fan the smoke"?

Nic: This was after Ramona left and my brother joined the group. We were playing all the little clubs and began to get attention. A producer in France offered us a record contract, and we thought, "Okay." The budget for this record was $3,000. We made the record, went to France, and had a huge hit. Then, we got a lot of attention from major labels. We had no plan; we just went with the tide of what was happening. We were getting a lot of attention, and we went for it. Suddenly, we had a manager, and it was very strange because we thought of ourselves as this little homebrew operation, and it turned into something much bigger than we ever imagined.

LP: Do you know the story of how you came to get attention from the label in France? What was the method through which he found you?

Nic: It's a strange story. This guy, a Frenchman living in New York, was perusing the clubs. He was in his early twenties and wanted to start a record label. He'd come from Paris, saw us, liked us, and somehow got Ramona's number. He called her and said, "I like this group called The Comateens. Do you know how to get in touch with them?" She was of two minds about whether to connect us, but she did. As a matter of fact, the day before he called, we had broken up the band. We thought it was too hard and depressing. Then, the next day, he called, wanting to make a record with us. So we said, "Good, let's do it." It was a tiny budget for an 8-track record, but people are still listening to it.

LP: Were you aware that the music had its own life, or has that been something reintroduced? What's been your relationship with Comateens' legacy?

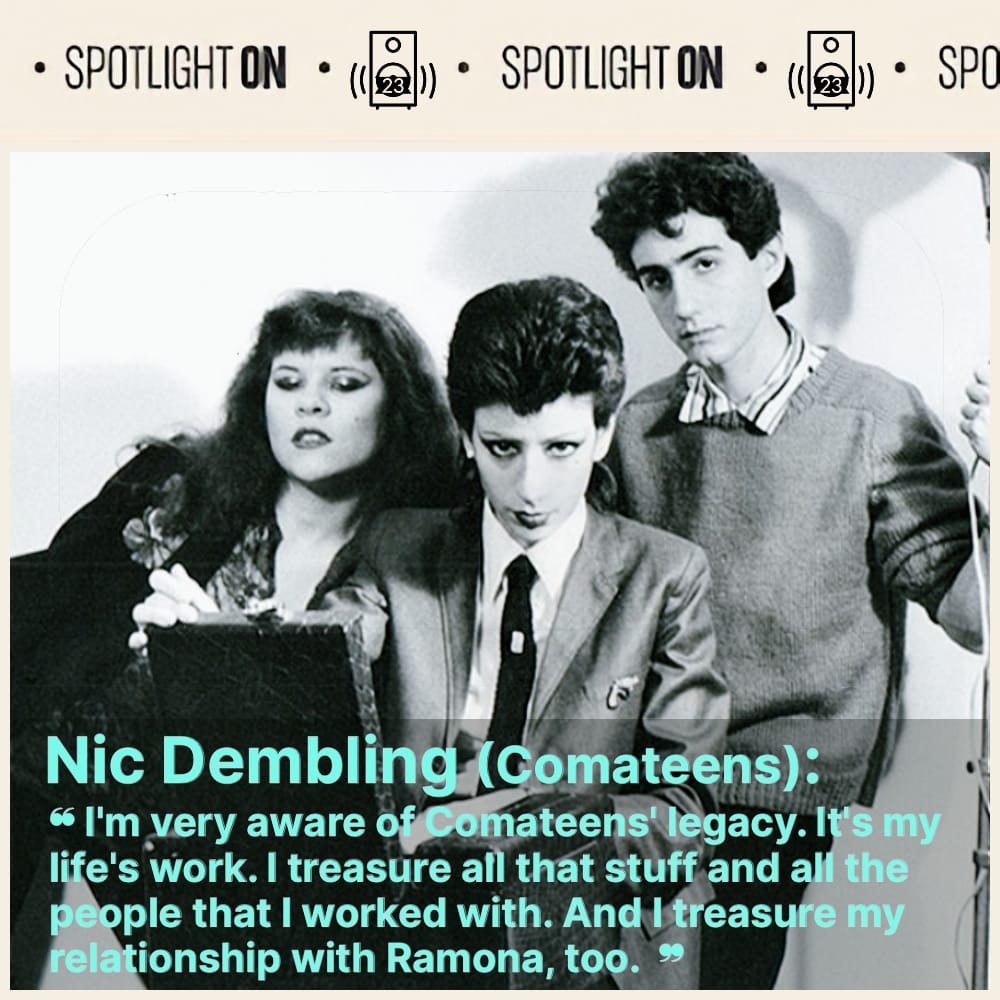

Nic: Because I admired old songwriters, the first thing I did when I got a song on vinyl was join ASCAP. I saw that as a badge of legitimacy. So, in that sense, I was very conscious of the business. Once we started rolling, I watched our business. I'm an archivist, and it's me who has kept the legacy going. When Ramona came out of nowhere after 20 years wanting to do this new release, I had all the tapes from 1978-79. I'm very aware of our legacy, and it's my life's work. I treasure it and all the people I worked with, including my relationship with Ramona.

LP: Is Comateens an ongoing concern? Is there a universe in which there's more music from that lineup or performance?

Nic: Ramona is not in a condition to play now. My brother passed away in 1987. I'm still in contact with Lynn, another member of the group. After my brother passed, I started writing songs for other artists and became a professional songwriter. My music is still out there; it's just not with me performing it. We've never discussed continuing Comateens per se. This is now a legacy project.

LP: You mentioned being the archivist, and the website you've built is no joke. It's a fascinating monument to this work and time, providing resources for students or scholars of that era in New York.

Nic: I'm certainly a pack rat when it comes to recordings, work, and photographs. Many people I knew back then were in no shape to preserve what they did. I was never like that. I have every recording I've ever made and thousands of photographs. I'm always ready for legacy projects, and I like that. I don't know what anyone will do with all this when I'm gone, but it's been very useful for me.

LP: It should go to the New York Public Library, in my opinion.

Nic: I'd do that in a shot. Library of Congress, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

LP: It's hard to say this about New York, but I think you'll understand the sentiment, which is these micro scenes from around the country at a time when music was still so regionalized. It's such an important part of the post-war fabric of this country.

Nic: What's interesting is that all this was pre-internet, so you really had regional artistic scenes. Now, everything is homogenized because everything everyone does is instantly disseminated to the entire world. I think that flattens the uniqueness of various scenes. I'm glad we were creative in the pre-internet era. I like the internet now for distribution, but I'm glad we made our mark before it. The internet consumes and spits out creativity at an alarming rate.

LP: It's belied by the fact that we call creative output 'content.'

Nic: Exactly. I hate that word.

LP: Yeah, I hate that word. I really do. I've never thought, "Oh, I'm going to go down to the club tonight and consume some 'content.'" (laughter)

Nic: It's just horrible. I also don't like the expression 'dropped.' They 'dropped' the new episode, and they 'dropped' the new album. It makes it sound like garbage.

LP: Language matters. We've let business-to-business terms and industry jargon become consumer-facing, which really devalues a lot of what we do in the culture industry. 'Merchandise' is another one. Like, 'merchandise?' Do you really want your fans to buy 'merchandise?' Fans buy collectibles, memorabilia, souvenirs. That's value.

Nic: Because it means something emotionally to them.

LP: Yes. 'Merchandise' is like what's sitting in a warehouse waiting to be discounted.

Nic: Now, with AI, who knows? I don't even know what to say about AI and its potential to wreck the artistic landscape, but maybe it's a good thing. What do you think?

LP: I think of myself as part of the first generation that had computers in the home. I'm in my early fifties. I was always into technology. I studied computer science for a short time and never practiced in that discipline, but my career has been in entertainment and technology. For a long time, I was a techno-optimist or techno-utopian. But it's increasingly difficult to be excited about technology and social media, considering the corporatization of the internet and what that's done to our relationships, even between families. It's great, but I try not to demonize technology because it's how people use it that matters.

Nic: It's just a delivery system, really, isn't it?

LP: Yeah. However, I also question whether technology doesn't have its own point of view. I don't mean that in terms of sentience, but that you have to have a lot of faith in technology and the institutions that have failed us repeatedly. Any new, game-changing technology is assumed to be used beneficially. Our ability to create and deploy technology moves faster than our ability to even stop and think about the implications. We don't model out the implications at all, and then we live with them.

Nic: You know what I don't like? The cloud. I don't use the cloud. I don't like the concept of some faceless corporation with a server somewhere holding all my stuff. I don't think it's necessary to use the cloud.

LP: It's interesting. My son is 19 and in art school. He has an attachable hard drive because he doesn't want his stuff in the cloud. That gives me hope because I see his generation turning their backs on some of the convenience. They value the soul of it. That gives me optimism.

Nic: So, were you a clubgoer when you were younger?

LP: I was always a rock guy. Later in life, I got into more interesting music.

Nic: Where did you grow up?

LP: I was raised outside of New Haven, Connecticut. Then I moved to New York in the mid-'90s and was there for about 20 years. Now, I'm just outside of Seattle. But, yes, if you mean clubs, not dance clubs but rock clubs and jazz clubs. When I moved to New York, I sought out any remnants of your era, like The Kitchen and The Knitting Factory.

Nic: Did you go to CBGBs at least once?

LP: Yeah. When I first moved to New York, I lived on East 11th between First and Second. I intentionally made that pilgrimage as a fan of the beats, and that era of music, and even the loft jazz scene, was resonant in my head. Not much of it was left by the time I got there, but to walk those same streets meant a lot.

Nic: You can't imagine what a mess New York was in 1977. Those neighborhoods were basically like Beirut. Burned out, and we were proud of it. We loved walking those streets because there was no pressure to be anything. It was a little dangerous but an amazing environment for artistic creation.

LP: It's funny now if you take somebody through Tompkins Square Park. You literally have to watch old film footage or look at photographs to understand that it was not a place you wanted to hang out with the kids on a Sunday afternoon.

Nic: Absolutely not. But we thought we were the outcasts, and this was our place. We were proud of not going above 14th Street.

LP: I held that ethos for a while, too. It's fascinating to hear from someone who lived it. Everybody has their New York, and I like to think that there are still people who have their own New York, different from the one I had, the one you had, or even Allen Ginsberg's, but it's their New York. It's an important place for that.

Nic: I grew up on the Upper West Side of New York in the late '60s, early '70s. That was an incredible artistic crucible. Isaac Bashevis Singer lived down the street. The whole place was vibrating with artistic endeavor, different but just as powerful as downtown.

LP: If you don't mind me asking, I'm curious about your family history with the Jaffes. Were you connected to that part of your history growing up?

Nic: Oh, yes. Sam was my great-uncle. I didn't see him often because I lived in New York, and he lived in Hollywood. I have beautiful letters from him. He was in his own world, a movie star, but I'm very proud of being connected. He was extraordinary, not just a great actor but a mathematician, a composer. His friends, like Zero Mostel… and his son Tobias is a close friend of mine. They were magical.

LP: I find it interesting because of the era and the Jewish artistic and intellectual milieu and its significance on American culture, which isn't often discussed. I've been fascinated by the Catskills and its impact on American comedy and early television. You can't disentangle the story of Eastern European migration to the East Coast from so much of our culture and post-war intellectual tradition.

Nic: No question. Zero was a big part of that, the whole Catskill scene. Then Zero and Sam got blacklisted. I have letters about Sam's blacklist, which was torturous. Have you seen 'The Front' with Woody Allen? It's about the blacklist and the effect it had on the Jewish artistic community.

LP: What are you up to next?

Nic: I'm pleased with these interviews about the record. I never thought these songs would see the light of day. Jim Reynolds, who runs the record company releasing this, is a soldier of the scene. I'll continue to write music. Maybe we'll get some more Comateens stuff out. It could be fun to do that.

LP: What remains to come out? Is this about repositioning the existing catalog, or do you have things in your archives?

Nic: There is other stuff that could come out, yes. And I have those tapes.

LP: Well, Nic, thank you for making time.

Nic: My pleasure. Thank you, Lawrence.

Are you enjoyng our work?

If so, please support our focus on independent artists, thinkers and creators.

Here's how:

If financial support is not right for you, please continue to enjoy our work and

sign up for free updates.

Comments