This piece was originally published by All About Jazz on November 3, 2011

Tango music, which like jazz has had a long and complex history often entwined with issues of class, has been present in the Americas for well over 100 years. As popular music, tango was in many ways the main (only?) rival to jazz in in the dancehalls of the 1930s and 1940s.

Also like jazz, tango after World War II moved out of the ballrooms and into clubs and concert halls, becoming music to listen to and watch, with a much diminished or even non-existent role for dancing. While saxophonist Charlie Parker and the other early beboppers were leading this transformation in jazz, Argentinean-born bandeneon player Astor Piazzolla was doing the same for tango. Throughout his career Piazzolla was concerned with the elevation and growth of the form. As a composer he led the genre into its first confluences with "serious" music—with jazz, modern classical and baroque elements all in the mix.

Piazzolla was equally concerned with his own commercial success, especially in America and Europe. This success would come for him, but in the late 1950s ambition led the artist to push a record specifically for US consumption: Take Me Dancing! The Latin Rhythms Of Astor Piazola & His Quintet(yes the artist's name was misspelled on his own record). An example of its commercial intent: no track breaks the three-minute mark.

As far as truth in advertising goes, "Latin Rhythms" fit the bill. As much mambo as tango, the record is not nearly the "artistic sin" Piazzolla would claim in later years, but it was in no way a commercial success. And it was by no means an inspired work.

At least not until Pablo Aslan decided to listen to it again, that is. What Aslan discovered was a "rhythmic approach that obscured the writing," and therefore a creative challenge, a bit of salvage work. Aslan set out to use the original arrangements of the compositions, which individually had intriguing bits of melody, as starting points for a more fully realized integration of jazz and tango, more in keeping with Piazzolla's own true artistry. With the arrangements largely intact, Aslan and his quintet found room to breathe, adding tasteful, if restrained, improvisations throughout.

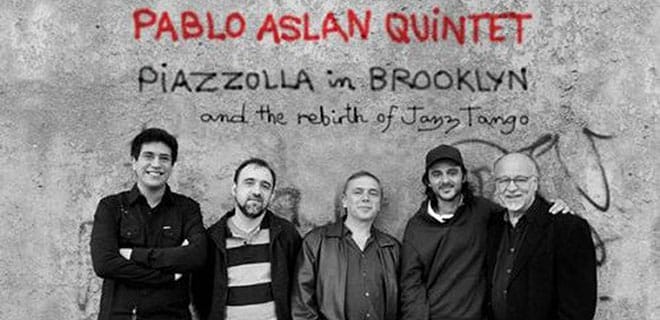

The resulting record, Piazzolla In Brooklyn (carrying the subtitle "and the rebirth of Jazz Tango") is, on balance, a successful one, given Aslan's intention, though not particularly ground breaking. Before a single note is played the concept and provenance begins to feel a bit gimmicky. Much emphasis is made in the liner notes (by writer Fernando Gonzalez and with a brief essay by Aslan himself) of the genesis of the project and the peculiarity of the Take Me Dancing! album. It is almost as if the current work cannot stand on its own and needs to be constantly compared to the "monstrosity," in Piazolla's words, that is Take Me Dancing!

Where Pizzolla's record was repetitive and dynamically flat, Aslan has wisely varied the tempos and certainly improved upon the fidelity. Pianist Abel Rogantini has a lyrical quality to his playing that adds much-needed colour to an essentially rhythmic musical style. He, along with Aslan's "re- arrangements," is the true star here, though the entire quintet avails itself well.

As a form, "jazz tango" may be fully realized. Perhaps the only innovations left are to be found in the future integrations of other instruments or traditions with the heavy lifting being done by arrangers and not composers. Piazzolla In Brooklyn is not an essential recording in this artist's or genre's canon, but it is a highly listenable and tasteful representative of where the form stands in 2011. It also re-contextualizes and ultimately redeems a career low point of an important innovator.

Tracks: La Calle 92; Counterpoint; Dedita; Laura; Lullaby Of Birdland; Oscar Peterson; Plus Ultra; Show Off; Something Strange; Triunfal.

Personnel: Pablo Aslan: bass; Gustavo Bergalli: trumpet; Nicols Enrich: bandoneon; Daniel "Pipi" Piazzolla: drums; Abel Rogantini: piano.

Comments