Passepartout Duo, a groundbreaking musical partnership between pianist Nicoletta Favari and percussionist Christopher Salvito, have been enchanting global audiences with their distinctive approach to sound exploration. Since the collaboration began in 2015, the duo has crafted a rich blend of electro-acoustic textures, fluid rhythms, and original instrumentation, challenging traditional perceptions of music and how we experience it. Their work is deeply experimental, featuring a continually evolving array of handcrafted instruments, from analog circuits and traditional percussion to complex textile installations and repurposed objects. In this interview, we explore the creative journey behind their latest album Argot, the development of the instrument Chromaplane in partnership with KOMA Elektronik, their residency in Tunis, and their forthcoming performance in London.

Speech Melody

Arina Korenyu: The title of the album, Argot, suggests a focus on language. How does the concept of language play a role in your music?

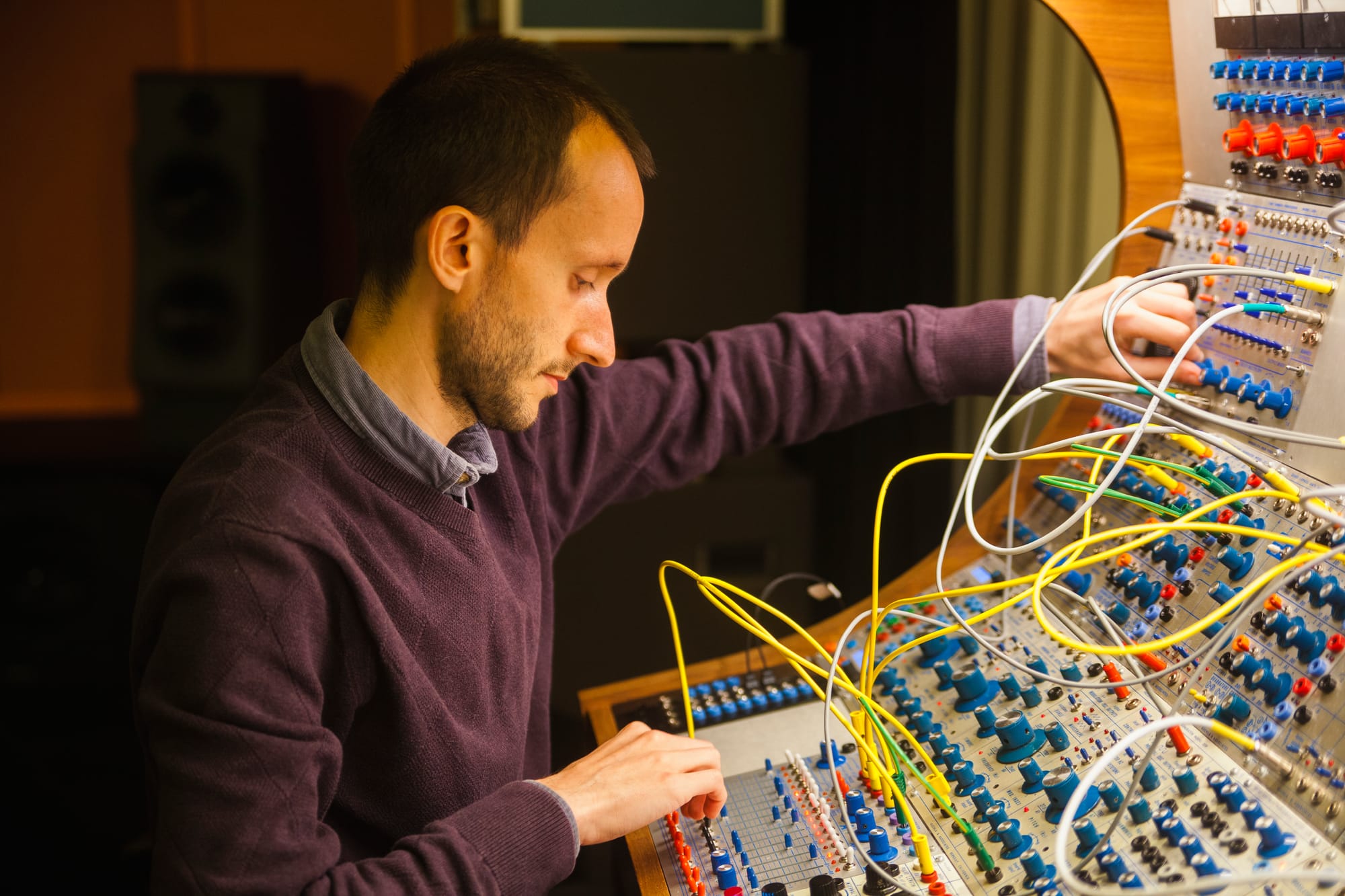

Christopher Salvito: One of the key inspirations for composing music comes from a technique called speech melody. We were inspired by composers like Peter Ablinger and other classical musicians who have used similar techniques. However, in our case, we wanted to reinterpret the synthesizer's voice as a form of speech—something akin to spoken word. Each piece began with an improvisation on a synthesizer patch, which was then transcribed as though it were spoken language, using a technique we call "speech melody."

Nicoletta Favari: In a more abstract and conceptual sense, we're fascinated by ideas like treating something as a voice, even though we don't work with voice, text, or words. We're also intrigued by the concept of secret languages, the idea of codes between language and machines. There's a common thread between musical instruments, technology, computers, and calculators, which we find interesting. All of these ideas blend in our minds.

Ultimately, our challenge is to extract the most musical expression from whatever “language” the machines speak—whether it’s an acoustic piano or a synthesizer. The foundation of every piece is the idea of communication between machines and acoustic instruments. The core research concept explores how to communicate from machine to human and between acoustic and electronic instruments.

Arina: How did you approach the challenge of merging acoustic and electronic worlds?

Christopher: The idea of transcription is really powerful for us. Electronic instruments can sometimes seem cold, unapproachable, or synthetic, but especially with older machines, they have an organic quality. By transcribing their sounds onto an acoustic instrument, we bring out the pure, organic essence that was always there.

Nicoletta: Once you know that the musical material will eventually be transcribed and performed by a person, it influences how you compose or improvise. You approach it differently, with that performance aspect in mind.

Christopher: One of the most beautiful things about combining the piano and synthesizer is that there's no concern about what would traditionally work on the piano. The synthesizer might play fast, awkward patterns or rhythms that are irregular and amorphous—many of the rhythms on the album are almost arhythmic, like gestural movements. Nico has to figure out how to make it work on the piano. It's refreshing to have that push in a non-human direction. It takes you out of what you're used to or what you would normally play on the instrument.

Nicoletta: The strong unison between the two is very important for us. Maintaining a balance where the electronic and piano elements coexist without overpowering the other is crucial.

Secret Personalities

Arina: You've mentioned that much of the material on Argot feels "discovered rather than composed." How do you balance structure and spontaneity when creating? Is there a point where you allow the music to completely flow freely, or do you maintain certain guidelines?

Nicoletta: We don't see improvisation as completely free. Instead, we think of it more as having guidelines or rather constraints. What I mean is that we often work with collaborators who are hard to pin down, especially since we're always traveling. People often ask how travel inspires our music, and we believe that different people and places influence our work, though it's hard to pinpoint exactly how.

In a way, it's similar with the instruments we use—they become like a third performer in the process. These instruments have so much personality and character. We chose synthesizers like the Buchla because they have distinct, almost secret personalities. Even their random sources are unique, and we wanted to let them "speak" in this improvisational space.

Christopher: I think of the synthesizer patch as a set of rules for the machine, but there’s still a lot of uncertainty within those rules. Then, as you interact with the synthesizer and play it, the sense of discovery happens.

You set up the framework—for example, the tonality and the overall backdrop of the piece—but the direction the music takes depends on both the machine and how you play it. There's this moment of discovery as you explore. Afterward, you transcribe what you've played, especially onto the piano, and the piano clarifies the sound, bringing out a pure, crystalline intonation of what was already there.

Once that clear transcription is in place, my ear starts to hear new harmonies and harmonic movements that weren't immediately obvious. The piano's clarity removes any ambiguity in the musical direction because, with transcription, you have to make clear decisions—there are no "maybe" or "in-between" notes.

When I start hearing those harmonies, it feels like another moment of discovery because they weren't something I consciously thought about during the synthesizer improvisation, but they were always there. This process, for me, really feels like a discovery, a co-composition between us and the machine, just like Nico described.

Arina: The album's music is unpredictable and lacks typical rhythmic backing. What challenges or new creative opportunities did you encounter by stepping away from traditional rhythms and structures?

Nicoletta: I think the rhythm is probably the most unique aspect of the work. While the harmonies are composed in a way that's more accessible or "human," the rhythm remains original. It's unpredictable to the ear, and even though we make some adjustments to ensure it can be played along with the synthesizer, the rhythm makes it impossible for us to perform this project live.

Christopher: Oh, yeah. The whole process takes time. It's not something that happens instantly. First, you have the synthesizer part, which you then transcribe for the piano.

Arina: In general, how does Argot compare to your previous albums? Were there any significant changes in your creative process or new ideas you wanted to explore this time besides the speech melody technique you were talking about already?

Christopher: Speech melody technique was a big part of it. In 2021, we released an EP called Epigrams, and for that project, we had access to a Buchla 100 series, one of the earliest Buchla instruments. We had it for a short time and created a set of pieces that was only about ten minutes long.

That was the first time we tried combining speech melody with piano, which inspired us. We had been waiting for the right opportunity to explore it further, and the studio at EMS gave us that chance. It was the first time we worked on an album where the concept was predetermined before we started. We knew exactly what we wanted to do with the instruments.

It was a unique artistic opportunity to dive into something with a clear vision for the beginning, middle, and end. Normally, our process involves developing ideas as we go, so the direction isn't always clear.

Another major difference is that it's a studio album. Our usual approach is very live-focused, emphasizing what it means to share the stage as a duo and the importance of our connection when playing together. But we never actually played together on this album in the same room. We played the synthesizers together, and then Nico recorded the piano separately. It was a very different approach, more conceptual and studio-based rather than a live, two-person performance.

The final big difference is that we collaborated with other musicians outside our duo for the first time. On one track, we had a flute player performing traditional Japanese flutes, a string quartet from the U.S. on two tracks, and a double bassist on another. This collaboration with other musicians was a completely new approach for us.

We also gave our collaborators a lot of freedom in their contributions. We wanted them to have the space to approach their parts in their own way. We explained the concept to them—how we used the speech melody idea with the piano—and asked them to think about how they would transcribe or communicate with the electronic track using their instrument.

We provided a more specific score for the string quartet because their part was more defined. The double bass and the traditional flutes were improvised.

Chromaplane

Arina: I would also like to talk about a new instrument you developed with KOMA Elektronik: Chromaplane. How did the idea for the Chromaplane come about, and what were the key goals you wanted to achieve with this project?

Christopher: The very first prototype of the Chromaplane was created in 2021, just for ourselves, as an instrument we could perform with. Whenever we create an instrument, we aim to make something portable to play together and use to write music. The Chromaplane came about in exactly that way. It was designed with those same goals in mind.

Nicoletta: The Chromaplane is a portable reconfiguration of a textile and sound installation we created for a small gallery in Denmark. While setting up the exhibition and experimenting with it, we realized how fun and expressive the tool we had was. So, we redesigned the whole thing into a simple, A4-sized plate.

Christopher: We’ve been interested in using the microphone as a musical instrument for several years. We explored this in various ways, and the Chromaplane was the most recent approach we tried. It felt very expressive and connected to my background as a percussionist and Nico's as a pianist. We both felt that it was something we could play in a deeply expressive way.

From there, we started writing music for it and playing it regularly. During concerts, we noticed curiosity around the Chromaplane—people were always eager to know what it was and how it worked. So, we thought creating an instrument that others could enjoy would be a great opportunity.

We approached KOMA with the idea of releasing it as a product, and they were interested. Since then, we've slowly developed newer versions with added features—some suggested by KOMA and others by us—to make it more enjoyable and accessible for different types of musicians to play.

Nicoletta: The product was launched as a Kickstarter campaign in July 2024, and now we're about to start shipping it.

Christopher: Around five hundred people have ordered the instrument, so we're excited to see what other musicians do with it. As for the goal, I think that's it—to see how others play and interact with the instrument, discover what they create, and explore where it can go. We're also interested in building a community and seeing what the future holds for it.

Arina: How does the Chromaplane differ from other synthesizers, especially when it comes to the tactile experience of playing it? What unique aspects of sound and interaction does it offer to musicians?

Christopher: This interface is particularly expressive because it relies on the electromagnetic field. It responds the same way a microphone or speaker does, with a natural taper similar to the distance between a microphone and a sound source. This makes it inherently expressive and immediate in a way that other types of sensors can be harder to work with to achieve the same level of expressiveness.

When compared to other instruments, the interface of the Chromaplane is different. On a keyboard, you have a fixed set of notes, and while you can be expressive, the order of the notes is always tied to a scale. If you jump across the keyboard, you're physically leaping a long distance.

With the Chromaplane, you can independently choose a set of notes and their relationships—both in pitch and spatial arrangement. This means you can have a large interval in one spot and a small interval in another, and you can create a mix between those two notes. This decoupling of pitch and space allows for a different way of thinking about harmony and melody. It changes how you approach playing the notes and thinking about tuning.

This has greatly impacted how we write music for the instrument. We create different material than we would working with a keyboard. It also forces us to set specific constraints for ourselves since there's a limited set of notes and a more geometric approach to arranging them. This leads to a different way of composing and writing material.

Nicoletta: You can sometimes think of musical instruments as easy or difficult to play. For example, we often think of the piano as easy because once you place your hands on the keyboard, the notes are there. Of course, it's easier than instruments like the violin, where you must tune and find the right intonation. The same could be true for synthesizers, handpans, or other instruments.

However, compared to the hand pan, the Chromaplane offers more depth. It's not just about the ten notes on the surface. There's also the patching interface, which allows you to shape the sound in a much deeper way. So, for those interested in exploring the electronic side of music, the Chromaplane provides a valuable tool for that as well.

Synthesizers on Breadboards

Arina: Right now, you are at Dar Meso in Tunis, where you have co-organized the residency "Babbasawt Sound Lab." What is the main goal of the Sound Lab?

Nicoletta: The goal is to bring visiting and local artists together to share their experiences with sound and musical instrument building. It's as simple as that. Based on our experience, we’ll present our approach involving synthesizers and electronic components. Then, our local peer, Rami Harrabi, will share his experience with traditional Tunisian instruments, like flutes and drums, using materials such as skin, bamboo, and reeds. We'll also have interventions in the city and end with final performances.

Christopher: It's been about a week, and during the workshops, everyone has been building different synthesizers on breadboards. Ultimately, each person has created a unique instrument with which to experiment. It's been really interesting to see the different results.

Nicoletta: The goal is to help everyone learn about the instruments they're familiar with from different perspectives while also introducing them to new instruments they might not know about.

Arina: You've mentioned how traveling often influences your music. With both local and visiting artists involved in this project, how do you see this cross-cultural exchange impacting the work they create together?

Nicoletta: I think everyone is curious, which is fantastic.

Christopher: I tend to think more about how specific people have impacted me rather than places since experiences in a place are tied to your connection to it. So, I see the influence happening more through the specific people interacting with one another and their unique backgrounds. I'd say that's the essence of cultural exchange.

Arina: You will have a performance with Inoyama Land at Cafe Oto in London on February 25th, 2025. Could you tell us what visitors can expect from the performance?

Christopher: This concert is primarily based on our previous album, which was a collaboration with Inoyama Land.

Nicoletta: We're joining them because we worked on this album together. Since we're so far apart geographically, we don't get to see them often.

Christopher: We collaborated on the album during a one-day session, our first time playing together. Since then, we've had a concert in Japan at a festival called Each Story. This will be our third live performance together. We'll do a live set inspired by the album session but with plenty of improvisation and different instruments. That's happening on the 25th.

Nicoletta: This is also their first time performing outside of Japan. Considering they've had a career spanning several decades—almost forty years as a duo—remarkably, they've never played outside of Japan before. It's an exciting moment.

Visit Passepartout Duo at passepartoutduo.com and follow the duo on Bluesky, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube. Purchase Passepartout Duo's Argot on Bandcamp or Qobuz and listen on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmPeter Thomas Webb

The TonearmPeter Thomas Webb

Comments