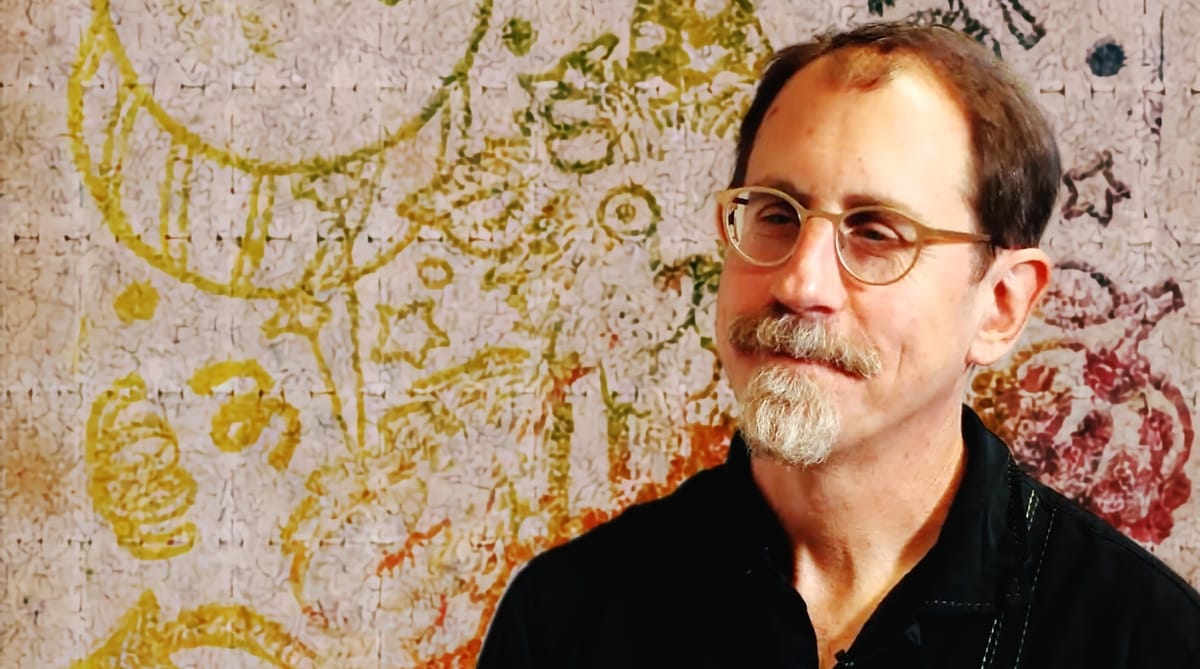

Ken Goffman, aka R.U. Sirius, has lived at the crossroads of counterculture and digital futurism for decades. As founder of the cyberculture magazine Mondo 2000, he drove critical conversations about technology throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, a time when the future was rife with possibility. His mix of psychedelia, techno-skepticism, and cultural critique has manifested through various musical projects, books, and publications, establishing him as a distinctive voice across multiple eras of digital culture. Was he a true believer, or was he a gadfly on a mission to poke holes in consensus reality? Yes, he was.

His current musical project, R.U. Sirius & Phriendz, advances his tradition of cultural disruption with a new album, The Smarter Kings of Deliria. Released digitally in February 2025, it features work from the past decade plus remixes of tracks from his 1982 band, Party Dogs. Working mainly with producer PizzaT, Sirius crafts a sonic mix of punk, electronica, and industrial sounds, hammering "a rusty nine-inch nail directly into the fontanelle of the 2025 zeitgeist." With lyrics examining NFTs, crypto-culture, authoritarianism, and our tenuous grip on reality, the album reflects what Sirius describes as our "delirious and cracked" cultural moment.

R.U. and I have been in an on-again, off-again dialogue on these topics since we first spoke at length for a May 2024 episode of Spotlight On. Please enjoy the latest public installment of that ongoing conversation. Deliria collaborator PizzaT chimed in with some thoughts as well.

Lawrence Peryer: Your musical projects have existed alongside your editorial and writing career, poking their heads out from time to time over the years. Was music ever intended as your primary creative outlet, or has it functioned more as a complementary form of expression?

R.U. Sirius: The first thing I ever did that was public was to write for and publish an underground newspaper in Binghamton, New York, in the early 1970s. So I think my first choice was not to be a writer or musician but to be part of "the revolution"—a kind of New Left Freak utopian revolution that everyone talked about in 1970 when I turned eighteen and graduated from high school. That was my young dream—my only ambition. So, in a way, everything after that is a compromise with reality. Once the revolution collapsed, the idea that the world expects me to do anything at all seemed like an imposition.

Sometime around 1973, I started writing some lyrics, and not long after that, I did some recordings with someone named Leon Glow (real name) that got played on the local college radio. One of the songs, "Reggae Ripoff," created a small kerfuffle. In some ways, it's an early example of the R.U. Sirius style of self-subverting protest lyrics. In other words, on the left-leaning side of things but, at the same time, kind of wrong and twisted. These are the lyrics:

In Kingston town the white man come

Bring a suitcase full of rum

Soon that suitcase full of tape

Big label record to demonstrate

And it-a reggae ripoff reggae

Reggae ripoff reggae

They play the songs they want to play

And we don’t have a thing to say

In Jamaica we spend all our lives

Making music all the time

Big spliff of ganja just one dime

But righteous tokin’ still a crime

And it-a reggae ripoff reggae

Reggae ripoff reggae

They play the songs they want to play

And we don’t have a thing to say

We’ve all heard Jimmy sing his song

We know it’s hard to get along

But one thing Jimmy Cliff don’t know

He don’t know where my ganja grow

And it-a reggae ripoff reggae

Reggae ripoff reggae

They play the songs they want to play

And we don’t have a thing to say

A crisis occurred because a DJ who used to play it thought it was an authentic reggae song and learned it wasn't. It was by two goofy white guys. Not only that, we'd recorded it using an analog synthesizer! Shades of future R.U. Sirius crimes against authenticity! So, there was a crisis meeting at the radio station to discuss whether it was okay to play the song. I guess it's good that students in the 1970s wrestled with questions around cultural appropriation, although I don't think that was the language then. It's a complex area of discourse, and we were, in part, satirizing those engaged in it.

If I might indulge in a brag, I think this simple short song and the act of recording it is not just a double-edged sword; it might be triple-edged, but I will leave it to others to unpack. A further amusing aspect of this little event is that the students assumed I was just being naive because I was a local townie ragamuffin who looked like a total hippie. I kind of had a group of friends with sophisticated, very dark senses of humor. We thought the college kids, mostly from New York City and Long Island, were kind of obvious. I guess the word now would be "basic." There's some kind of class politics in all that.

Anyway, as things evolved, I would have liked to have made my bones, such as it is, as a singer and lyricist more than as a writer and editor. Sexier, more fun.

Lawrence: How does your music relate to your written work and cultural criticism? Could you talk about any unified creative or philosophical vision there might be?

R.U. Sirius: Essays, even by someone with a tricksy sensibility like myself, tend to be didactic. Although the lyrics are sometimes pointed, the need for a kind of musicality gives them a feeling, to me, of absolute play. Someone else might think I'm making a rough or even harsh statement like “What will you wear to the new civil war," but to me, they tend to be rhymes that pop into my head and give me a kick. I always hear them in my mind as playful.

Sometimes, I'll even have the vague feeling that maybe I shouldn't say something, but it's such a perfect little rhyme I can't let it go. I'm just going to have to use it. I would tend not to do that in an essay format, even in a humor-oriented piece, but it feels right in the context of music.

Lawrence: You've rubbed shoulders and collaborated with many notable figures over the years. How did your partnership with PizzaT and the other "Phriendz" on this album come about? What can you tell us about the relationships behind the music?

R.U. Sirius: I'm not sure exactly when I approached PizzaT about making music to my lyrics. He might be able to tell you.

I'll just say that he's usually far away, and we work at a distance. Some of the songs have my voice. On some, he does everything. I just gave him the lyrics and some ideas about the approach. Sometimes, he does the vocals. Sometimes, there are other vocals, some of which may be, shall we say, inauthentic. I give notes on everything in progress or after the "first draft," so I might be kind of the co-producer.

When I originally posted some of our collaborations, I put Phriendz up front so it would be "Phriendz with R.U. Sirius." But PizzaT wanted to make the album "R.U. Sirius & Phriendz," and I've come to feel like it's somehow correct for R.U. Sirius to be identified with it. In earlier albums, like with Party Dogs and Mondo Vanilli, I did all or most of the vocals, but various circumstances have made that less of an option. I'm perfectly happy to have a Warholesque relationship with musical or other media projects now. Slap my name on it! Or slap its name on it, maybe. I have some separation from my persona.

PizzaT: I heard from a friend that Ken/R.U. was working on a new book about Mondo 2000 and trying to make some remixes. I jumped at the opportunity because it fit perfectly with the concept of the band Phriendz. The band has characters, and R.U. Sirius jumping on the ship was and still is radical.

Lawrence: The new album, The Smarter Kings of Deliria,at covers musical styles from punk to electronica. Would you mind unpacking the process a little bit? For example, do the lyrics come first? Do you hear music before writing words? Neither? Both?

R.U. Sirius: Largely, yes, I provide the lyrics, and sometimes I have music in my head, and somehow that gets interpreted as if by osmosis. I will say that some of the songs are over a decade old, while some were done in a frenzy over the last half year or so as we vibed on what the feel of the album as an entire piece needed to be. Actually, two pieces are remixes of songs originally recorded by Party Dogs in 1982, but they work thematically with the flow of the album.

PizzaT: The year I started Phriendz was also when a friend linked me up with Ken/R.U. to do remixes of his older songs. When making "On the Beam," I reconstructed the chorus completely and then used the old song as a sample in the chorus. Then, Ken had lyrics he wanted to turn into songs. The band, being mostly composed of sentinel entities stuck in the internet, gave us some direction to go, and it really wanted a direction.

Ken would sometimes send a bunch of lyrics to pick from, or in other moments, he would want a song ASAP if it had something to do with current events. Phr!€ndz aka PHRIENDZ had only made one music video before our second music video with Ken.

Ken worked with Phriendz in the following years to remix two newer songs he had already recorded. By this time, we found a flow, and I realized we had a full album ready to be born.

I would send mixes of songs to Ken, and then he would communicate back on what it needed or did not. Then, Ken would get ideas on top of my ideas, and eventually, we would agree that the song was complete. (Laughter) Then, Ken had us remix one of our songs, "Dose the Pudding." Ken and I have recorded vocals outside at a park and also at his home.

R.U. Sirius: I'm stunned by how it coheres. Listening to the final mixes, I discovered how they needed to be ordered. I surprised myself.

Lawrence: If you were an R.U. AI, I would prompt you to be in ‘reflective mode’ for this one: You mentioned that some tracks on this album are remixes of your Party Dogs songs from 1982. What's it like revisiting music you created over forty years ago? How has your relationship with those songs changed?

R.U. Sirius: PizzaT remixed "President Mussolini" by Party Dogs, which was written in response to Ronald Reagan's firing of striking air traffic controllers. And PizzaT brought in Donald Trump's star vocal performance at my suggestion, along with some Benito and others. The entire thing was done during the campaign before Trump won his first election in 2016. I'm surprised by how well it works. The rest of the album seems to bring out the chaotic musical intensity he brought to the remix. While it was an intense protest song in its original form, now it's an expression of deliria! It kind of has an exploding shards feel, a fragmentation bomb.

Lawrence: What aspects of our current cultural moment were you trying to capture with the new record?

R.U. Sirius: It's in the album’s title. It's delirious and cracked, I think, in an extreme way. I mean, there's more extreme music being made, certainly, but there's something about the twistiness of this one that makes it a rusty nine-inch nail hammered hard into the fontanelle of the 2025 zeitgeist.

Lawrence: "Illusions of Agency" opens the album—a concept relevant to tech culture and political discourse. How does lyric writing allow you to explore and make sense of the world to the extent that there is any sense to be made?

R.U. Sirius: That one is kind of the banality of evil, and it's kind of the banality of good or evil. It might be seen as discouraging, but I think it's sort of a Buddhist insight—that agency is ultimately an illusion. But I'm saying too much. I like people to have their own interpretations. Anyway, the pursuit of power for its own sake is an element relevant to US and global politics of the moment. Generally, engaging in lyrics amidst the current madness (and let's not exclude the lyrics written during the Biden years) allows me to hone in on the potential for multiple interpretations of what's occurring by making political and cultural themes a particular type of field of play. The way that it intersects with rhyme and musicality gives it some levity and a touch of psychedelic mindfuckery. I don't think anyone is mixing lyrical content this dark that's also this whimsical, at least not in dealing with social/political tropes.

Lawrence: Your track "I'm Against NFTs Remix" reflects a critical stance toward aspects of digital culture. In our talks, you and I have touched on how hard it is to be a techno-optimist, which is how I think of us both (I'll avoid "techno utopian"!). I mean, you have always had a stick-in-the-eye element to your writing and theorizing, but I wonder, could you talk a little specifically about how your perspective on technology has evolved since your early Mondo 2000 days?

R.U. Sirius: There's kind of a playful mix of techno-gloom and techno-optimism across the entire album. The song "St. Jude Was A Cypherpunk" might seem almost aggressively excited about cryptocurrency and space travel, but it also has a bunch of ironic twists. The remix from the 1982 song "On The Beam" by Party Dogs is almost a straightforward sort-of embrace of the Learyite agenda of that time, i.e., Space Migration Intelligence Increase and Life Extension, although even that had a very subtle ambiguity.

"I'm Against NFTs" is more in the current dystopian vein. The tech discourse amongst thoughtful people now is around "enshitification" and technofeudalism. I fundamentally agree with those analyses, although it's a bit much to try to explain them in a music-oriented interview. NFTs specifically are or were a strange phenomenon. The argument made by a lot of digital optimists in the Mondo 2000 nineties was that content on the internet would be difficult or impossible to commodify because digital stuff is trivial to copy, and anyone with access to the internet can get that digital stuff no matter where they were located physically. Capitalism has proved to be effective at firewalling off digital stuff in certain ways and creating monopolistic and monopsonistic feudal estates.

But marketing a singular piece of nonphysical digital creative content to a single buyer or to a limited number of buyers as a sort of imitation of the market for physical artworks seems pretty absurd. In the brief rush that existed for high valuations of NFTs, people were, in some sense, not even buying exclusive or limited ownership of the digital thing. They were just buying an imaginary relationship to a work that maybe the creator acknowledged in a note. It's a perfect realization of Marx's prediction that everything solid melts into the air and a great expression of virtualization under conditions of capital exchange. The payoff ending, "Get your money worth nothing / And your clicks for free,” pokes at the crypto aspect of it, although it could prove to be about mainstream US dollars as well. I guess we'll see.

Lawrence: Indeed. That story is being written as we speak. The Mondo Vanilli project conceptually played with ideas of authenticity and reality. In what ways, if any, does The Smarter Kings of Deliria continue exploring those themes?

R.U. Sirius: It's not even strange anymore. I see acts pop up on music sites, and I wonder if they exist or are entirely made of and by AI.

Phriendz is largely made up of virtual members, cartoonish images, what PizzaT refers to as sentinel entities, occasionally animated. And there's some AI in our mix. I've attempted to pretend to be at live shows. No one seems to mind.

I'm particularly fond of the very sort of white businessman voice reciting "The World Is Flat." It's extraordinary how effective the blatant use of incongruous voices barely evincing human affect can be in bringing out the qualities of a song. Of course, PizzaT adds some soaring lyrical guitar work that also, at other points, fragments and scrapes and claws appropriately. The entire thing, I think, is lovely and disconcerting.

I also think a lot of the lyrics across the entire album sneak up close to the edge of invoking violence and class war while masking it with silliness or hair dye in a way that plays with questions of authenticity in the scary context of the political moment. Is American fascism performative? Is resistance performative? Does everything, on some level, feel performative? Are we fully in the simulacrum? What will you wear to the new civil war?

The physicality of suffering from want at scale is—and will be—really shocking in a hypermediated civilization. And the harsher it gets, it creates more—not less—of a break with reality. There's a sense that we're in a simulacrum and that physicality and its needs and pains are an imposition. We actually kind of predicted that as one of the possible outcomes of virtualization back in the Mondo 90s.

Lawrence: Did you ever get to close the loop with Trent Reznor about what happened (and did not happen) with the Mondo Vanilli record back in the 90s?

R.U. Sirius: No. Trent is presumably too busy, too much in demand, and out of reach. And I'd like to point out that I never sent a gang of acid-drenched hippie chicks to Cielo Drive to express my disappointment. Seriously, though, I think he would dig this album. Mr. Reznor, if you're reading this, reach out.

Lawrence: Between tracks like "President Mussolini Makes The Planes Run On Time" and "The World Is Flat," satire abounds. There is certainly a Zappa-esque element present.

R.U. Sirius: Zappa is certainly an influence. And I was a Yippie, which involved humor not just as commentary but as actual activism. I don't know how to separate the two. Whether writing lyrics or prose, I have to go with what I can conjure. Looking for words is a desperate act.

Lawrence: Looking back at your musical output across different decades, what threads of continuity do you see? Has your musical mission remained consistent?

R.U. Sirius: Well, I've only written the music to one song amidst all my musical efforts, two chords that made up "Romping Thru The Jungle" by Party Dogs. I seem to remember that I sang a few bars of "I'm Against NFTs," a version that is included in the Deliria album, and passed that on to Scrappi DuChamp of Mondo Vanilli, who turned it into a complete song with help from Blag Dahlia of The Dwarves. Anyway, a lot has been dependent on who I can get with. But I find that with Mondo Vanilli and then with Phriendz, there's a similarity: a kind of excess but also a kind of really serious attention to production. I'd like to think I influenced both of those aspects.

Lawrence: Who are some of the musical artists you have taken inspiration from, and in what ways, over your life? And what's the next thing you’ll listen to after we are done here?

R.U. Sirius: I found my voice—literally my singing voice—learning the entire Rolling Stones catalog in 1976 with a friend who was obsessed with them. So, I'll have to acknowledge that. And Sir Mick is an underrated lyrical ironist, or he was in his prime, anyway. Before that, listening to Iggy sing gave me the feeling... "Hey, I think I can do that." At the same time, I always loved what musical pranksters ranging from The Beatles to Brian Eno could make happen by playing that great pop culture instrument known as the recording studio.

Next up for listening? I seem to have the Yoko Ono album Approximately Infinite Universe cued up. It was made during and soon after John and Yoko's Yippie period, although, on the whole, it's more existential than political. And I imagine I will drift into some Bowie. Always Bowie. That's my favorite listening.

Check out R.U. Sirius on the Mondo 2000 website. You can also follow him on Bluesky and Instagram.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmR.U. Sirius

The TonearmR.U. Sirius

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments