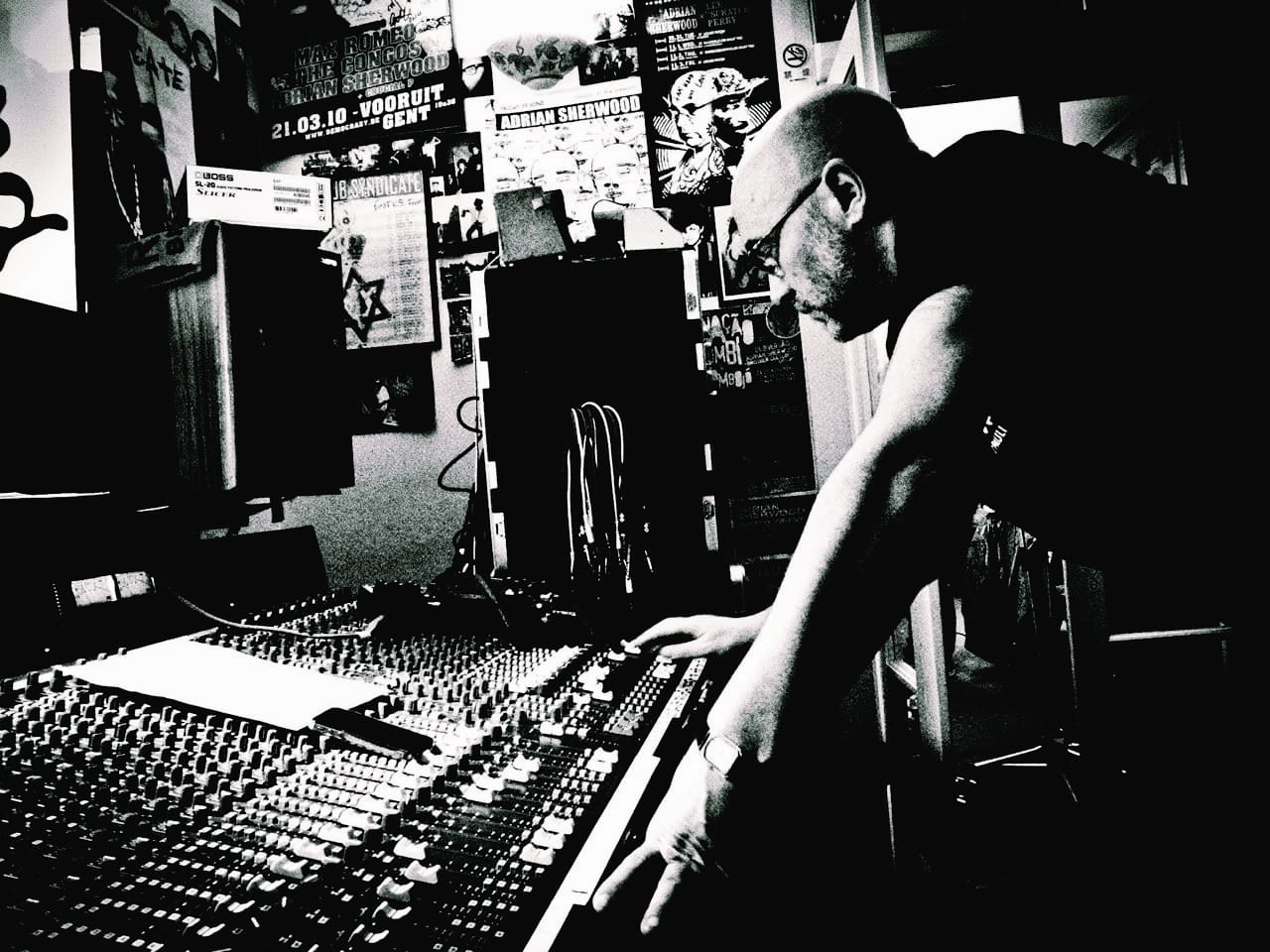

The mixing desk becomes more than equipment in Sherwood's hands; it transforms into an instrument of time and space. Each fader movement, each auxiliary send to a delay unit, each EQ adjustment serves as brushstrokes on an endless canvas. Through his landmark label On-U Sound, established as the 1970s bled into the 1980s, these techniques escaped their Jamaican origins and infiltrated post-punk, industrial music, and electronic dance cultures—casting ripples that continue to expand outward decades later.

Among Sherwood's most significant creative partnerships was his collaboration with Lincoln Valentine "Style" Scott, a drummer whose meticulous approach to percussion eventually formed the backbone of Dub Syndicate. What began as another vehicle for Sherwood's studio experimentation became symbiotic and revolutionary. Scott's elevation from session musician to bandleader and co-producer created a remarkable transatlantic dialogue—rhythms born in Kingston's humidity traveled across oceans to be ‘finessed’ under London's gray skies, then returned home transformed.

These conversations between continents receive proper documentation through the comprehensive Out Here On The Perimeter 1989-1996 reissue campaign. Following 2017's Ambience In Dub collection that excavated earlier material, this new archaeological dig focuses on the group's second creative phase when Scott took a more prominent role. During these years, Scott moved from a background figure to an essential creative partner, while simultaneously, Dub Syndicate evolved from a studio concept to a formidable live entity. Their music from this era caught the zeitgeist with uncanny precision—beloved equally by those who gathered around towering sound systems and those navigating the euphoric aftermath of acid house raves.

The four albums receiving vinyl resurrection—Strike The Balance (1989), Stoned Immaculate (1991), Echomania (1993), and Ital Breakfast (1996)—document a musical partnership operating at its creative zenith. Each record preserves a moment when reggae's traditional forms underwent radical deconstruction through Sherwood's notorious production approach while remaining anchored by Scott's rock-solid rhythmic foundation. Accompanying these classics comes Obscured By Version, a newly created set where Sherwood returns to the original multitrack tapes with fresh eyes and ears—discovering new artifacts within familiar terrain.

This collection arrives weighted with poignancy, serving as a cultural document and a memorial. Scott's drumbeat was permanently silenced in 2014 when he fell victim to senseless violence in his Jamaican home. Yet these recordings ensure that his rhythmic innovations continue their conversation with future generations—the drum patterns speaking with clarity long after the drummer himself has departed. Scott’s influence continues to breathe in the contemporary moment.

In our conversation, Sherwood reflects on the political dimensions of dub music, his collaborative process with Style Scott, and the legacy of Dub Syndicate as a project that always appealed across genre lines. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Michael Donaldson: In the context of the community around On-U Sound, do you see these albums as "political" in any way?

Adrian Sherwood: Well, I think, particularly with the whole of the On-U Sound stuff, it's very political because it just gathered good people. I mean, that's politics with people, isn't it? Mark Stewart was particularly politicized with his lyrics. But I think the instrumental stuff that we did and continue to do, if you go to dub dances or sound system dances, the bulk of the crowd tends to be quite politically aware, perhaps leaning towards caring about the planet a lot more than most human beings, and, you know, vegetarian or conscious people. So, I think the dub arena was one of the most conscious collectives going.

Michael: How much of the gear you used for the new mixes is the same as what was used on the original mixes? Is there anything you use now that you wish you had then or vice versa?

Adrian: I still use some of the same gear I used 40 years ago. I used Lexicon 224, the AMS reverb, and the AMS delay. I’ve used these since the early 1980s and still use them in our mixes.

Michael: I'm sure one thing you wish you had now was Style Scott. Was there some way to feel you were channeling his input?

Adrian: Style Scott did so much work with me. I finessed the recording of these tracks, the rhythms he recorded in Jamaica. Then, we overdubbed and finished them here. So, I overdubbed and finished some of them with him, like Timeboom X De Devil Dead and others like Stoned Immaculate.

He was there for some of it and not for some of it, and he trusted I was doing my job, and he did his in Jamaica. But with these tracks, I felt he was there because they were joint productions of his and mine. And to this day, I just feel very sick in my stomach about the loss of Style Scott.

Michael: How much is remixing your past work a memory machine for you? Did working on these mixes bring to mind any notable memories or stories you hadn't thought about since the original recording sessions of these Dub Syndicate albums?

Adrian: Well, in a real answer, no. Not really.

We were just revisiting the tapes and "nicing them up,” as the Jamaican saying goes. It wasn't really that I was doing lots of new versions or remixing particularly. We just sparkled some. And we used the approach of an album like Lego Dub (Ossie All Stars – Leggo Dub Part One) or something with the sound effects and things we'd had.

We just tried to update versions that had not been released. That’s what it was. They weren’t new mixes. They were original old mixes that Patrick Dokter, my dear friend in Holland, had when he looked through all the master tapes. We selected ones we thought were good. We did a couple of selective overdubs on two or three of them and created what I thought was quite an amusing little dub record.

Michael: Can you describe the process of working with Style Scott? He sent you backing tracks from Jamaica to flesh out and work on in London, correct?

Adrian: Well, it wasn't like that. To be honest, what happened goes back to Prince Far I. Prince Far I had recorded a lot of rhythms when I first met him when we were recording Cry Tuff Dub Encounter Chapter One. What he recorded sounded great. And, similarly to Obscured by Version, we took them in the studio, overdubbed instrumentation and sound effects, and tarted up the rhythms he'd mixed in Jamaica and produced. "Foggy Road Rhythm,” we recorded in London, and "The Message."

But then, going to Obscured by Version, Style brought the tapes from Jamaica. Some of them, the ones that I liked, we worked on together in the studio at the time. We overdubbed for vocals, samples, solos, Skip McDonald, and other musicians and turned them into what became the first co-productions we did, which was Time Boom X de Devil Dead. We co-produced quite a few tracks on that album together with Lee Perry. Then it led to the first Dub Syndicate album produced by him and me on the label, which was the great Stoned Immaculate album, followed by this batch, you know, Echomania, Ital Breakfast. And just before we did the Stoned Immaculate album, the first one, we had some of his productions that we did together from Jamaica, and once we'd recorded in London, that would become the Strike The Balance album. So, this bunch of the five albums together is like a complete set before he started his Lion and Roots label.

And, although I worked on those records on the Lion and Roots, they were put out by himself.

Michael: I'm curious how Style Scott came into your orbit and reinvigorated Dub Syndicate after the project's four-year break. Did Style Scott’s influence make Dub Syndicate a formidable live band?

Adrian: Very much so. Yeah. What happened after Creation Rebel collapsed, I used the name Dub Syndicate. And the first Dub Syndicate album was a studio project, and I think the first album was Charlie Fox and Eek-a-Roo (Don Campbell) on one track. That was Pounding System.

Every time Roots Radics, Style's Jamaican band, visited England, I had access to, you know, the hottest drummer in Jamaica at the time because Sly had gone international and Radics were laying all the rhythms down. Gregory Isaacs, Bunny Wailer, Eek-A-Mouse, Yellowman, on and on. So when he came, I was his friend from the 78/79 period. So he was amongst us, and I collected him from the hotel, hired him, and got George Oban, Lizard, or whoever on bass, and I'd record my rhythms in London. So, having access to him made my recordings sound brilliant because he's such a great player.

And what Style did that was unique before any session was that he could go anywhere, and you could hear it was him. He'd spend probably an hour tuning the drum kit, getting it to sound how he wanted it. If it were a hire kit on a show, a different one every night, he'd spend an hour tuning that drum kit. You could hear it was him because he had his way of setting the sound.

So he'd do that on recordings in England. Then, Roots Radics went a bit pear-shaped; he wasn't very happy with the setup. I think he was disillusioned with what happened with Bunny Wailer and Gregory. And he asked me, “Can I run with the Dub Syndicate?" So, for me, I was encouraging the Dub Syndicate shows.

One of our engineers, Alan, went there to do sampling. Before that, it was David Harrow doing sampling. We were trying to get it to evolve into Lee Perry's band. I think Style wasn't happy to be anybody’s backing man anymore, and then he took the reins and ran with Dub Syndicate as an instrumental band with samples.

Michael: Though the Dub Syndicate albums get filed in the "reggae" section of the record shop, there's so much else going on sonically. At the time of these original Dub Syndicate releases, genres were a lot more rigid than they are now. Is the time truly ripe for rediscovering Dub Syndicate?

Adrian: Yeah. I mean, if you look at the catalog, there are, well, I think, about nine Dub Syndicate records now, including this one on the On-U label. But there's also obviously Doctor Pablo and Dub Syndicate, and then there's a very good back catalog there for people to discover our works together. Then, there's the post-On-U Sound Dub Syndicate, where Style started to involve Capleton, Big Youth, and Gregory. He had some good guests on the post-On-U Sound ones that I still worked on. The recordings arrived from Jamaica; we'd overdub them in a day and mix them in a day, those albums. And they're really wonderful.

Some of those albums, like No Bed of Roses, are really good. But, the ones on On-U, we spent a lot of time on, and it wasn't like we were trying to be weird or different. It wasn't for the sake of it. It was just we, you know, we had a sonic link between us that was very good. And I would recommend people try to investigate and discover the works.

Hopefully, with this release, Out Here On The Perimeter, some new folk will discover them.

Learn more about Adrian Sherwood and Style Scott at on-usound.com. Purchase Out Here On The Perimeter (1989-1996) and the other Dub Syndicate reissues from the On-U Store or Bandcamp and listen on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments