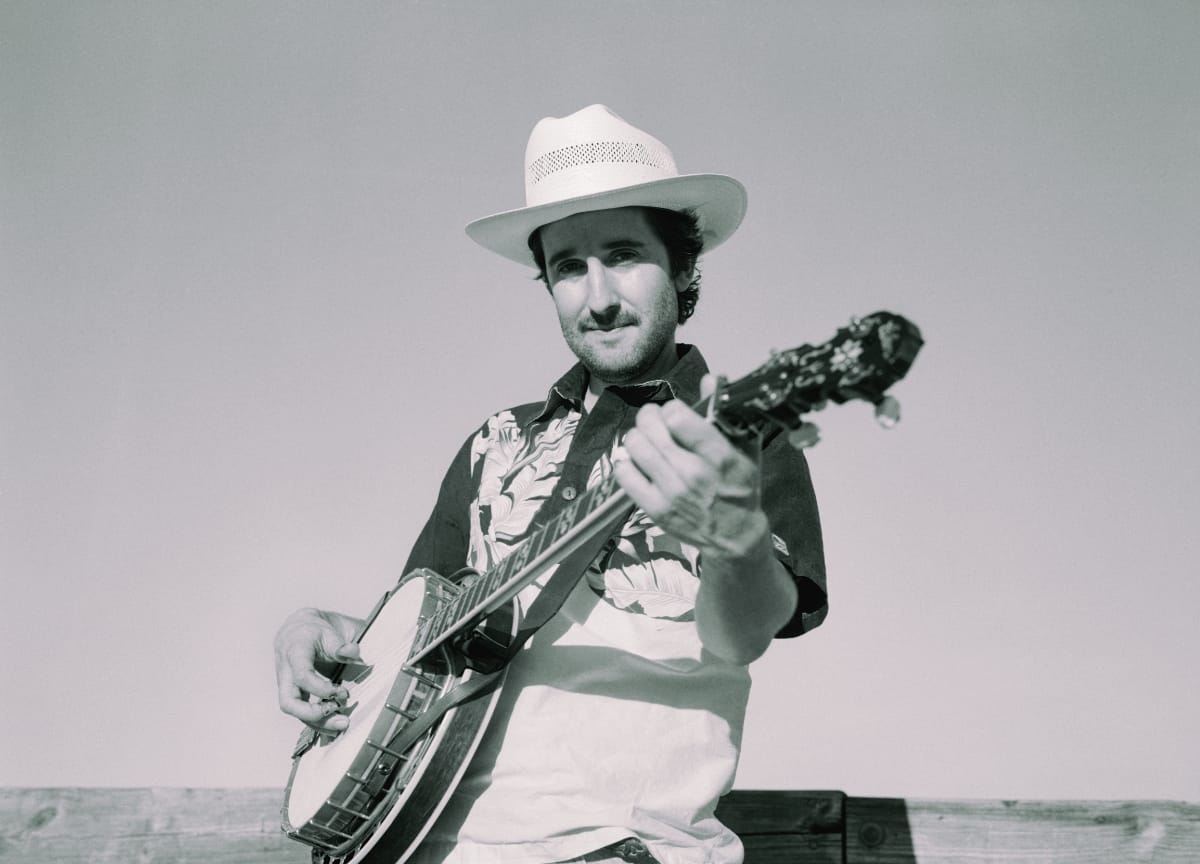

Max Wareham is no stranger to unearthing the past to influence the present. From songwriter to banjo teacher, author to archaeologist, Wareham has dedicated his career to exploring the storied past of bluegrass music and, by extension, American culture. DAGGOMIT!, his debut record, is a love letter to the classic sound and storytelling of bluegrass music, driven by a lifetime of his original experiences.

Wareham published Rudy Lyle: The Unsung Hero of the Five-String Banjo in 2022, a biography of the underrecognized banjo player who joined Bill Monroe from 1949 to 1951, and again for a stint in 1953. Wareham has volunteered on an archaeological dig site in East Tennessee during a sabbatical from music and has spent time translating poetry from the medieval era.

Bluegrass is having a big moment right now, to say the least, and DAGGOMIT! adds another piece to the colorful puzzle of one of America's oldest genres. Wareham's original tunes like "The Black & Gold" or "I Remember" fit snugly into the traditional mold of instrumental bluegrass music. "Heartaches" takes notes from Wareham's appreciation of jazz music, similar to the bebop-tinged compositions of David Grisman or Tony Rice. The record includes several vocal numbers featuring various members of the record's ensemble. "Hard Times Are Far Behind" brings the lonesome themes of heartbreak and wandering, co-written with Peter Rowan and featuring harmonies between Wareham and Laura Orshaw.

The record features a star-studded cast of Chris Eldridge and David Grier on guitar, Laura Orshaw on vocals and fiddle, Chris Henry on mandolin, Mike Bub on bass, and Larry Atamanuik on snare drum. Peter Rowan produced the record and lent his iconic voice to several tracks. Five-time Grammy Award-winning engineer Sean Sullivan was enlisted to record the project, Wareham's first as a solo artist.

In this interview, Max opens up about his transformation from jazz to bluegrass musician, how his research as an author into the history of bluegrass affected his outlook, the continuing longevity of his nearly 100-year-old main instrument, and how he aims to haunt the past rather than be haunted by it. The interview has been lightly edited for length, flow, and clarity.

Banjo Epiphany

Sam Bradley: Where did you grow up originally, and how did you start to get involved with bluegrass music?

Max Wareham: I grew up in central Connecticut, which is not exactly the hotbed of bluegrass music. I got into jazz guitar originally and moved to New York to go to school and study jazz guitar performance. While I was there, I was walking to class one day and walked past a musician on the street. She was playing banjo, and it was like an epiphany moment for me to hear the sound of that instrument. I thought, "That's what I have to do," so I got deep into it. I just dove in headfirst.

As I got into the banjo, my mom said, "Well, you know, Dad's cousin is a bluegrass musician." That turned out to be the guitarist, singer, and songwriter Peter Rowan, who I would later go on to seek out and learn from. Ultimately, I would join his band and record with him, and as it turns out, he produced this album, DAGGOMIT!, that I'm just getting out into the world.

Sam: What sort of artists or records were important to you in those early moments of getting involved with music? What is your relationship with that same stuff nowadays?

Max: I listened obsessively to late 1950s and 1960s jazz before I got into bluegrass. Everything from classic Blue Note recordings to avant-garde, free improvisation. I still listen to jazz every day. I’m a huge fan, and it’s such a big part of my musical identity, even if I’m not playing it in the form it's known.

But as I was getting into bluegrass, I was open. I hadn't yet learned to turn my nose up at anything, so I listened to everything. A lot of Old & In The Way, a band that featured Jerry Garcia on banjo and Peter himself on guitar and vocals. That was a huge starting point for me, but I was also listening to a lot of Old Crow Medicine Show. I hadn’t learned the differences between old-time and bluegrass at that point.

There also weren't many resources, at least not in New York City, that I could find to learn more about these differences. I had to try to learn by listening a bunch. I hadn't connected with any of the people who would become my teachers at that point. I guess now my relationship to that stuff is that I don't quite listen to Old & In The Way or Old Crow Medicine Show as much as I used to, but I still love it. I still love the music, and I can still hear that initial spark and feel the excitement I felt back when I listened to those groups.

Sam: I know that a lot of your work has been conducted through somewhat of a historian's perspective. What are your thoughts just on the general state of bluegrass? Whether it be the community, the fans, the audiences, or recorded projects. I'm curious about your insight as someone who has spent so much time studying the genre’s history.

Max: When I got into bluegrass, it was during the last great revival of bluegrass music—O Brother, Where Art Thou? You know, that's a thing I didn't mention because that's a soundtrack I listened to nonstop. I think we are going through another revival of bluegrass music, a revival of an interest in it at least. I think that's a beautiful thing. It's wonderful to get to ride on some of those waves that have been generated by people like Billy Strings and Molly Tuttle.

I think that there's a widening, a sort of cultural widening of the scope of bluegrass music. You're starting to see a lot more incorporation of the jam band aesthetic into what's accepted in bluegrass music, not that that's new exactly. I mean, hippies have been playing bluegrass for a long time, but it seems to have become a little bit more central in the aesthetic scope of the music. I think that's a positive.

We're seeing bluegrass music become more inclusive to different genders, sexual orientations, and ethnicities. I think people are becoming much more conscious that the roots of bluegrass music are actually very, very diverse.

I think it's a wonderful thing that's becoming more acknowledged in the scope of bluegrass music.

I am a little bit concerned about the pedagogy of bluegrass music, how it's taught, and how it's learned. We’re seeing that it's coming into schools and colleges more. I think that's neither good nor bad; it's both. But as someone who studied jazz in college, I see how easy it is for music to lose its cultural sense of place when it becomes something that can be graded or a craft that's either successful or unsuccessful.

The soul of bluegrass music has to do with people. It has to do with community, and it has to do with specific geographical places where the music came from. There's nothing wrong with studying music in school, but I haven't seen a curriculum that includes a cultural sense of place as central as how fast you can play or things that are more easily graded—technique, music theory, knowledge.

These are all good, but what makes people cry when they listen to music is its beauty and ability to connect to the heart. That comes from understanding the people who came before you and the places they came from.

Haunting the Past

Sam: On the other side of that coin, I read about many other projects you've worked on outside of the music world. Could you touch on that stuff a little bit? How do those experiences tie into what you pursue today?

Max: One of my earliest memories is sitting in the backyard of the house I grew up in, digging in the ground and taking a hose out, pouring water on the dirt so it turns into mud, then digging through it again. It was a joyful tactile experience, and I recognize how that experience was formative. I've pursued varying levels of seriousness and different expressions all relating to that experience of digging. I volunteered on an archaeological dig in East Tennessee, excavating a sixteenth-century Cherokee settlement. We were digging in the ground, looking for different bits of the culture of these people who lived on this field, and we found many things, too. It's pretty incredible.

Another thing I'm interested in is Middle English poetry, medieval English. It's not technically translating because our language came from that language, so we would technically call it modernization. I mean, you look at it, and there are letters that aren't in our alphabet and would make no sense to most modern English readers. I'm interested in this language in this period for a couple of reasons. One is as a songwriter; the language is incredibly musical. It's such a beautiful experience to hear this musical language that's similar but different to the one we use now and to try to pull some of the musical qualities from it and hopefully be able to use them in songs or the appreciation of other people's songs.

I'm also just interested in it because it's old. Going back to these primary texts, I recognize now, is another form of digging. One thing that has been a guiding star for me in my exploration of myself through music and art is this relationship to the past, this curiosity about what things were like. I'm trying to explore that through many angles and lenses.

I feel haunted by the past, too in many ways, by not only my past but the past civilizations or the past ways of looking at the world. I'm trying to figure out how to haunt the past instead of having the past haunt me. I’ve been chewing on this recently, and I'm starting to frame the course that my life is taking in this way. How do I become an active participant in this haunting rather than being the subject of it?

I think that by being active and exploring these different avenues, finding every perspective I can to put myself in different places in time is a way of haunting the past.

Sam: You said that modernizing poetry has been very influential in that way. What sort of differences come about in the songwriting process with a lyrical song versus an instrumental song?

Max: Writing the instrumental tunes is much easier for me because the scope is narrower. It's not using the human voice, just notes on the instrument and the natural sounds it can produce. So, for me, it's a lot easier and more universal.

I mean, a lot of music occurs in the natural world, like birds and thunderstorms in the summertime. I don't know if you ever had one of these plastic tubes that you whirl over your head as a kid. It makes these different sounds as you do it faster and faster, but that's like a naturally occurring scale. It’s called the overtone series. It's like a scale that exists in the physical universe. It doesn't even need a person to create it. You know, it's objective music that exists in the world. Tune writing, for me, is much easier because it's just everywhere, everywhere you look.

A song is the human coming into it and putting the voice to it. A lyrical song is more challenging because there are not only the words we choose and their specific musicality with each other, but there's the performance on it, how soulfully it can be sung. So yeah, I guess that's sort of how I view it.

The songs are a little more challenging but also a little bit more human in a way. I think incorporating the vocals is important in bluegrass music because it brings it down to earth and makes it more human and relatable. When I was setting out to make this album, I sought out the advice of some of my older mentors. One of the recurring things I was hearing was, "Well, look, it's 2025; nobody wants to listen to an instrumental banjo album other than banjo players." They said you need to have some songs because that's what's interesting to people, very broadly speaking.

Drawn to the Spontaneous

Sam: In what other ways has collaboration with your idols and mentors influenced this album?

Max: I think, especially coming from a background in jazz, I'm drawn to the spontaneous. Playing in Peter's band for a few years has been a pretty cool experience for many reasons, and one of those is that he's good at creating space musically and letting other musicians come in and fill that space. What happens when that space is allowed for other musicians to explore is that you go to places musically that you've never expected or sometimes that you never even knew about. It's a pretty beautiful thing, and I think it is a great way of bringing the audience or the listener into the creative process. This is a big part of how we played as a band and how we still play.

I had very few notions about the arrangements or even how each track would go and was deliberately trying to leave space for these people to do what they do so well. I'm so over the moon, so pleased with how it turned out because, you know, each of them would chime in at certain times and say, "Oh, well, I think I should do this part here."

For the last track on the album, "Miles," guitarist Chris Eldridge, who's affectionately known as Critter, did one take of it. We played through it, and he said, "You know what? I think I could play an intro for this song.” He just came up with this fingerstyle introduction that became an integral part of the tune. We tried to keep that spirit of spontaneity, space, and looseness, not in the playing but in the approach, alive. I think that process brings vitality to the music. It makes the music alive.

It's a great thing to see a band that's completely dialed and tight. They've got their stage banter scripted and everything. I think it's a very impressive experience, very beautiful. But for me, real life comes into the music when there's the element of chance. I think that you're trying to keep that alive in the sessions.

Sam: When it comes to both the studio and playing live, do you tend to rely on fully improvised breaks? Have you ever charted or got a rough outline for that?

Max: Yeah, that's a good question and something I've thought about, especially going back to the tradition and looking at what other people have done. If you look at somebody like Earl Scruggs, sort of the great hero of banjo playing, he would play the same break every night. He would have it perfectly planned out and play it so beautifully. He played it in a way that sounded like he was improvising and playing it for the first time. That's an approach that I think many people tend to take within the genre, especially when recording something and planning it out.

But listening to some alternate takes of Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass music, he kept it fresh. He was playing with some fire. That's something I realized about this banjo player who I wrote a book about, Rudy Lyle. He was doing the same while playing in Monroe's band. He didn't know what he was going to play before the break.

I say that in a sort of broad sense because the general rule here is to play the melody, whatever that means. It's a little bit more rooted than improvisation in jazz. Rudy Lyle and Bill Monroe were playing differently on every take. I think that also adds that sense of urgency to the music, a sense of life to the music.

On stage, anything can happen, and I try to stay tethered to the melody, but anything is possible within that framework. I don't have a set approach in the studio. Depending on the material, I might have worked up a break, and then we hit record, and I'll just improvise, knowing that I have the muscle memory of something I can expound upon in the moment.

Sam: I'm glad you mentioned Rudy and your book because I was also curious about that. Not only how going through that research and writing process changed your relationship with just music, but if that was something you could see yourself doing again.

Max: Oh, absolutely. I'm just starting to work on another book. This one is a collaboration with the banjo player Butch Robins, who is from Southwest Virginia. He's an older gentleman who played banjo in Bill Monroe's band in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

He is himself sort of a bluegrass philosopher, and he was a disciple of Monroe’s and studied the music on a level many people haven't even considered. I mean, he's a deep thinker. He and I are working on a book about the history of the music, what the music really is, and how it's misunderstood in many contemporary contexts.

The experience of having done the Rudy book made me feel bonafide, having paid the dues. It made me feel like I deserved to be a musician. You know, I already was a musician, but having had the experience for my internal self made me feel like I paid some dues anyway, at least in terms of the lineage of the music. That's a wonderful thing to be able to feel. It's an empowerment, I guess.

Sam: Yeah, I've always liked how it relates to that, the phrase "I've studied the blade," because it's almost like you're diving full well into the knowledge of something but then being able to come back and wield it, to use it in your own sort of way. In a sense, it's still just taking from the past to influence the present, which seems like a theme of this record and your journey as a whole.

What sort of weight does the idea of a solo debut carry that a full band effort might not?

Max: There's no hiding when it's a solo debut. When it's a band, it's like, "Here I am, part of this greater whole, and I've made a contribution to it," but what it amounts to is something greater than myself as an individual. The fact of the matter with this solo debut is that that's also true because every musician involved made some really beautiful and individual contributions. In the way that it's presented to the world, it's all me, and it's all up to me. That carries a weight with it, and it also brings a lot of beauty to it.

I love that phrase "I've studied the blade," and I think it's a sort of public-facing thing to say, "Hey, this is me. I exist. I'm somebody," you know? That's empowering, too! I think that the next album I'm going to record will be a little bit more about the band I've been working with. They're called the National Bluegrass Team, and I want this album to be a bit more like a well-oiled machine-type band.

The previous release, DAGGOMIT!, has so many other musicians involved. I mean, I wrote many of those tunes right there in the studio, and it was a very spontaneous experience. The next one I want to do will be with the band I'll have been touring with all this year, and we'll have really worked the arrangements through for months. Of course, there’ll still be a lot of spontaneity, but yeah, I'm looking forward to doing it again while taking a different approach this time.

Sam: What gear are you using in the studio or on tour?

Max: My main banjo is from 1927, so it's almost one hundred years old. Like many of these old banjos, it’s sort of a Frankenstein with some more modern parts. Bluegrass musicians have an obsession with tone. The tones that come from these older instruments are unique, I think. There's a certain lore with the old instruments.

The one thing that draws me to playing an old instrument is that it is way older than I am, and it's going to live longer than I will, too. I'll probably have this instrument my whole life, and there'll come a day when I'm not here anymore, but the instrument still is. Something about that is appealing to me, and to think, "Oh, if this instrument could tell me stories, I can't imagine what it would say."

That lore and that obsession with the old tones are enough to drive bluegrass musicians past the point of reason, and they still bring their instruments on the road. It's all about the tone and the sort of magic of the old instruments. That said, I've invested in a good flight case, and it's done me well.

Sam: Is there anything in particular that you want people to take away from the record?

Max: One thing I wanted to convey in the production of this record is a sense of levity. Mostly through the album art and through the title, you know, it's a little silly. The album art is sort of a reference to the Nickelodeon cartoons I watched growing up. Bluegrass musicians tend to approach the music with an almost austere sense of purpose. It's very serious, and that's fine, but I think that when we incorporate a sense of light-heartedness into things, things tend to loosen up slightly. I think it tends to make room for—well, I don't know what it makes room for actually, but that's something that I was trying to be deliberate about doing. We want to bring that sense of fun.

Visit Max Wareham at maxwareham.com and follow him on Instagram and YouTube. Purchase DAGGOMIT! on CD or LP directly from Max and digitally from Qobuz. You can also listen to the album on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments