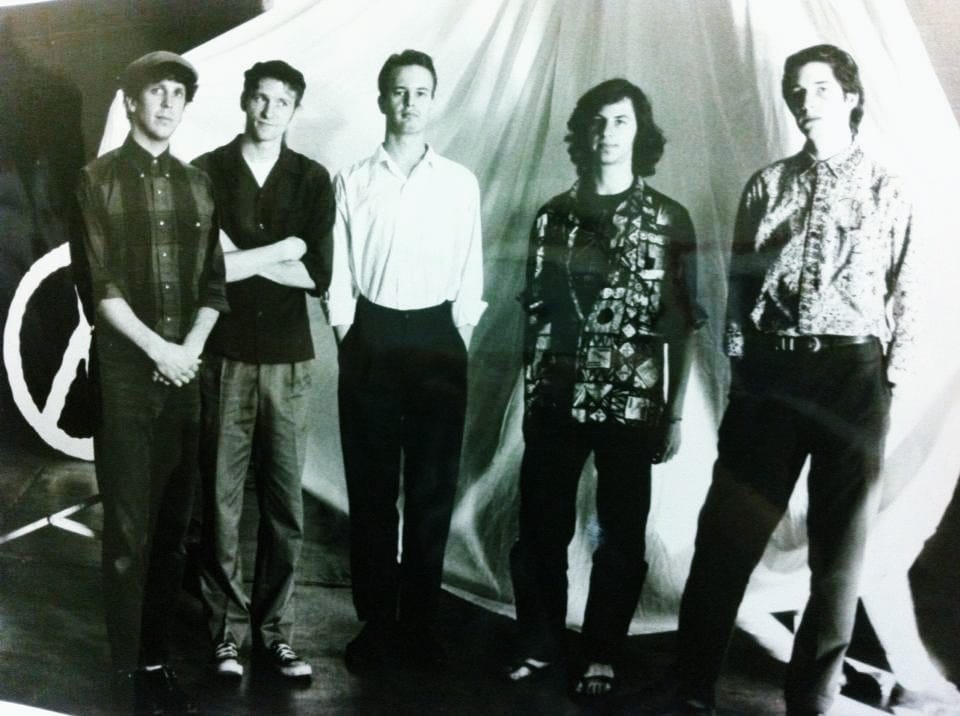

Greg Lisher has spent decades defining himself through six strings and amplified electricity, his guitar work with Camper Van Beethoven since 1985 helping to map the contours of American alternative music. Those mash-ups of Eastern folk, punk urgency, and country inflections became sonic cartography for countless genre-wandering listeners. When Camper fractured in 1990 (though they would reassemble in 2002), Lisher continued charting progressive territories with Monks of Doom alongside Victor Krummenacher, David Immerglück, and Chris Pederson—fellow travelers from the Camper constellation.

The geography of a musician's identity becomes fixed in listeners' minds. We expect permanence where there should be fluid evolution. Lisher's first hesitant steps away from this fixed position came through Handed Down the Wire (2001) and Trains Change (2007)—singer-songwriter efforts that maintained guitar as the centerpiece while experimenting with voice. Then, Songs From the Imperial Garden (2020) quietly removed lyrics, letting instruments carry narrative weight. But these were mere preparatory sketches for what would become Underwater Detection Method—an album title that perfectly captures its genesis as a submersion into unfamiliar creative depths.

There's a profound vulnerability in surrendering virtuosity. Lisher found himself in his late fifties becoming a beginner again—taking piano lessons, puzzling through software manuals, allowing himself not to know. This exercise in the ‘beginner’s mind’ created space to explore fascinations dating back to his pre-Camper days. Yellow Magic Orchestra had planted seeds in the early 1980s that would take four decades to sprout. Musical notation became visual art as he sketched digital MIDI notes across software grids, his guitar-trained fingers now directing virtual instruments he couldn't yet physically play.

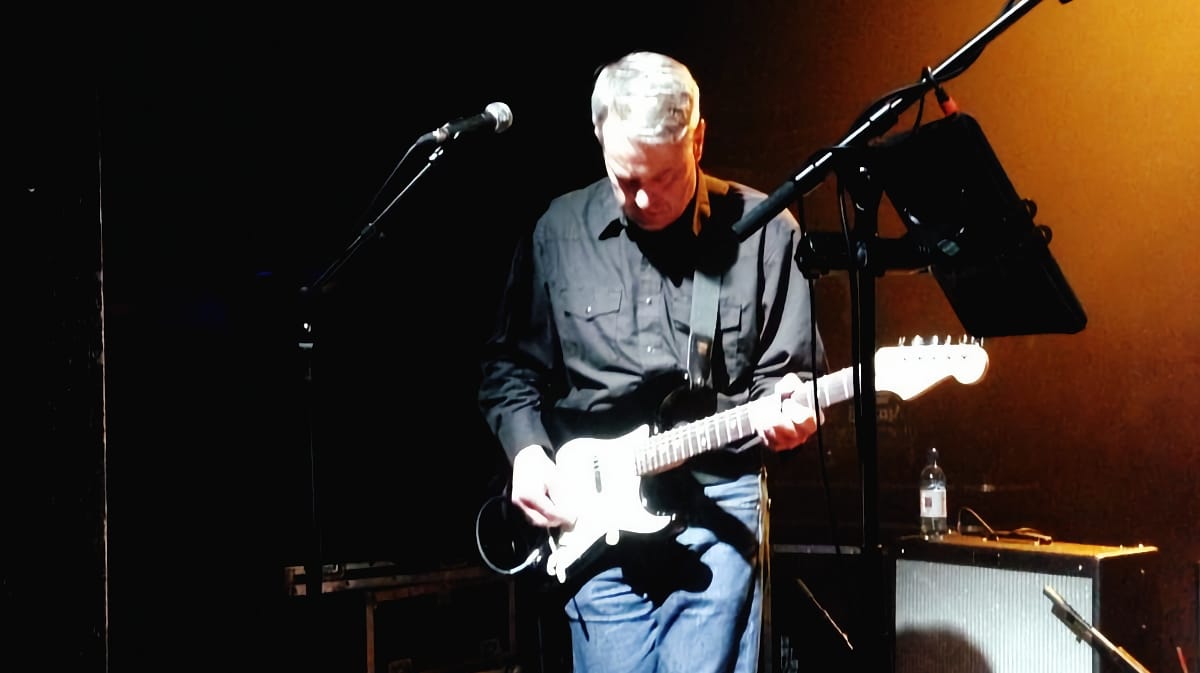

Underwater Detection Method arrives on Independent Project Records four decades after the label released Camper Van Beethoven's debut—a beautiful symmetry that speaks to artistic cycles and returns. While conceived in electronic isolation, the album gradually incorporated collaborative elements—live drums, strings, bass, and, yes, Lisher's guitar playing. Below its electronic textures, Underwater Detection Method dives into depths where only curiosity provides navigation.

Host Lawrence Peryer recently spoke with Greg Lisher on the Spotlight On podcast. The conversation captures Greg’s journey into electronic music-making and the trial-and-error aspects of leaning into a new musical discipline. The two also discuss song titles for wordless music, the ‘secret sauce’ of mixing rigid electronics with human expression, and whether longtime fans will accept Greg’s new musical direction. Feel free to listen to the entire chat in the below Spotlight On podcast player. The interview transcription has been edited for length, flow, and clarity.

Like a New World

Lawrence Peryer: I was trying to think of other artists who have mastered one form and then began again in another style or form. I was thinking about David Lynch. He went from visual art to film and then music. Joni Mitchell is a good one, guitar and painting. What's it like to have such proficiency and identification with one area within music and then take the leap on these last two records into something quite new?

Greg Lisher: I view my solo records as an opportunity to do things I can't do in my other bands. I did my first two solo records as a singer-songwriter-based work. After the second one, I thought maybe it was time to try something different, put the vocals aside, and focus on the music.

While doing the singer-songwriter thing, I was singing and playing melodies and chord progressions. The music didn’t feel complete if you took my singing and the melody out. I wanted more from the music side of things. That's when I did my last solo record, Songs from the Imperial Garden. I decided to experiment, put the singer-songwriting thing aside, and try an instrumental record, moving in a different direction.

Most of that record came from demos I’d worked on for years. I had a bunch of four-track demos, and I met up with David Immerglück, the other guitar player in one of my bands, the Monks of Doom. He's in the Counting Crows now. He's kind of like my musical confidant. I told him what I was interested in doing, gave him all the songs, and he was interested in producing the record.

We started that one in 2010 and finished it in 2012. As we were finishing it, before I could get it out, I got this new software that gave me access to synthesizers and electronic tools. It was another opportunity to keep learning, and I just couldn't stop myself. I wanted to keep going, keep learning how all this worked, and focus on moving forward and learning as much as possible.

The pandemic and other events then allowed me to focus more on my musical creativity and learning as a musician. With all this downtime, I figured now was the time to do this. If one of my bands, Camper Van Beethoven, starts up again and we start playing shows and touring, then the opportunities for me to do my own thing diminish. You have to schedule more and plan more.

Lawrence: When you talk about the learning process, is there a lot of experimentation, both with the tools themselves and the compositions?

Greg: Oh yeah. I've always been able to fool around and come up with a piano part or idea for one of my songs, but I didn't know how to play keyboards. I didn't know anything about synthesizers. I had skills in programming drum machines because I used to do that long ago while doing these four-track demos for my singer-songwriter stuff.

I was always good at putting stuff together, but this was like a new world. So, suddenly, I’m making a keyboard-based record with synthesizers, and I don’t know how to play keyboards or program synthesizers.

Lawrence: It's kind of punk rock! (laughter)

Greg: Yeah, I figured it was like a cliff I wanted to dive off of. It is a bit punk rock, I guess. I did it because I wanted to understand how to do things in this realm of making music. I thought, now's my opportunity; let's dig in.

There were no demos when I created these songs because everything started from scratch. I never knew where anything was going to go. The whole thing started by scrolling through different preset sounds and finding the ones I was attracted to. Those sounds made me play and write a certain way. They just drove my mind in whatever direction that would be.

Then, I programmed drum patterns and created bass lines, melodies, and chord progressions, just starting to put things together. I purchased a book on Reason and went through it from top to bottom. It has exercises that provide examples of how to get started. I used these exercises to get started, and as I did, I started coming up with my ideas.

As I started putting the songs together, working with these sounds, coming up with ideas, and creating sections arranged into songs, I started learning how to use the software, program synthesizers, and play keyboards. At a certain point in the process, I thought taking some piano lessons would probably be a good idea, so I did. I got a piano teacher and started taking piano lessons.

It was a real growth explosion for me.

Everything by Hand

Lawrence: As someone who has played guitar for so long, what was that experience? What did the piano reveal to you?

Greg: It just helped me better understand keyboards and use them as a tool for songwriting. The funny thing is, I started taking piano lessons, but I don't think I've ever written a song on the piano. I just used that knowledge to apply it when I was working with all these software synthesizers. It really helped.

I worked within the MIDI sequencer because I couldn’t play keyboards when I started this record. I was drawing out a lot of notes and doing a lot of cutting and pasting to put arrangements together. I'd never really worked that way before. I'd used Pro Tools and knew I could edit things and create arrangements, but because I didn't have many skills on the keyboards, it was very visual, and I was writing stuff out. There was such a big visual aspect to everything I was doing. The funny thing is, as the record continued and I started taking lessons, I went back and ended up playing everything by hand.

Lawrence: So, really, the original sequencer recordings, in their way, served as demos.

Greg: Yes, I hadn't thought of that, but yes, exactly. (laughter) So I guess I just went back and kind of refined stuff.

Lawrence: Would you have released those if you didn’t take the piano lessons and went back and listened to the sequencer versions of the tracks?

Greg: Yeah, they weren't bad. It ended up not being far from what I had originally, but when you're drawing MIDI notes, I noticed I would draw chords right up to the next chord. When I went back to play it for real, there would be this space from when it took me to pick up my hand to get to the next chord. All of a sudden, there started being all this air and space. When you lay your fingers down on a chord, not every finger comes down exactly at the same time as the other fingers. When I started, everything was quantized, rigid, and square; everything was square and almost computer-like to the grid. When I got back into it, I knew what the music sounded like. I just wanted it to sound human and not constructed on a computer.

Lawrence: The idea of where humanity meets technology is really interesting. Not to necessarily over-philosophize about it, but it's a conversation I've had here with other artists, specifically regarding the early years of synthesizer music or what we might identify from the mid-seventies to mid-eighties.

We often return to that music because of its analog aspect and because you still had to play the synthesizers instead of simply programming them. The more people like you I talk to and hear stories of wanting to bring humanity into technology-driven music, the more that thesis resonates; those two together are the secret sauce.

Greg: Yeah, I'm with you. Software is great for being able to mock things up. I can mock up a drum kit and get an idea of how I would want a real drummer to play on the song or what I would imagine the drums doing on the recording. Or, if I wanted to create a string part or something, I could use string samples to mock that up. There's so much of it that's kind of a means to an end in a certain way because I start by mocking things up, but then I get real musicians to replace whatever I programmed on the drums, most of the time.

But I still like drum machines and combining the two elements of real drums and drum machines. I would never get a real drummer to play like a drum machine or use a drum machine to sound like a real drummer.

Lawrence: It's its own instrument. It's its own sound.

Greg: They all have their strengths. The same thing with the strings—I got this guy down in Southern California to take the arrangements I came up with using these string samples, and he played all the parts himself with viola, cello, and violin.

The only thing left on the recordings was the software synthesizers, to which I added guitar. Originally, I wanted to keep it all software, but as I learned and interacted with other people, they said, "Hey, what about doing this?" And I thought, "I hadn't thought of that."

We started adding some drums on the record, and then immediately thought I should add real bass to this and double all the bass synth lines with real bass because that would make it warmer and fatter. As we started doing all this stuff, the record started blooming. Originally, I didn't want to play guitar, but one of my friends, a mentor to me and a producer-engineer, said, "Man, why sell yourself short? You could benefit from adding yourself as a player into this."

The mentor that I'm talking about, his name is Bruce Kaphan. He's known as a pedal steel player. He plays many instruments. He's a producer. He mixes. He has a studio that's about just an hour away from me. I went to him and said, "I've got this idea. I'm doing this project and want to learn how to mix.” So, that was another part of this whole thing, working with him.

Like Looking at a Painting

Lawrence: You mentioned your first two solo albums being more in the singer-songwriter vein, and I'm curious how working without lyrics allows you to express meaning and intent. How do you think about narrative, or how do you think about meaning in the absence of lyrics?

Greg: That was one of the reasons I wanted to try making instrumental music: I knew that there was a challenge sitting there for me. Coming up with song titles is hard because there's no lyrical content. Sometimes, I have to use my imagination. It's like looking at a painting in a museum and saying, "What does this make you think of?"

Even when making electronic music, my roots lie in traditional guitar music. There are still chord progressions, melodies, drum patterns, and bass lines on this record. It's not just soundscapes or anything like that. I'm trying to merge everything because I'm a really big fan of some artists who make records that are much more abstract than what I do. I don't see that as being exactly what I do.

People that know me for what I do, whether it's playing guitar in Camper Van Beethoven, or the Monks of Doom, or doing all this other stuff—I was thinking, "Oh, these people, I'm kind of curious how they're going to react to it or what they're going to think," because I was thinking they probably don't know a lot of the music that I'm into or that I was listening to when I made this.

Some people were like, "Oh yeah, like Tangerine Dream." Or then someone else was like, "Oh, this is Greg Lisher's Kid A," referring to the Radiohead record. I hadn't seen that one coming, but it makes sense.

Lawrence: Yeah, your reference points.

Greg: Yes, and it's funny, too, because synthesizers, especially in the seventies, have a role in rock music, and they have a role in prog music. I feel like my other band, the Monks of Doom, we were touching off on a lot of prog. There were a lot of prog influences, not necessarily from me but from some of the other band members. But when I did this record, I think those prog influences came into this.

Lawrence: Guy takes a few piano lessons, and now he's Keith Emerson! (laughter)

Greg: I know, right? I would never be able to do anything like that.

Lawrence: You talked a little bit about how you approach song titles and how you arrive at them. Do you ever start with a notebook with a list of potential titles, or does a title ever come up to you while working on a song?

Greg: I have a list in the notes app on my phone that I've been running for years, and I've got three hundred song titles that I just come up with in my head. I'm walking around and come up with it, thinking, "Oh, that's a good idea." That happens a lot. Then, other times, none of those titles will fit. I have to come up with something else. Some of this music may make me feel a certain way, remind me of something I've done, or if I can't draw from personal experiences, then I just have to use my imagination and see what I come up with.

Lawrence: On Songs from the Imperial Garden, I feel that, whether or not it's an explicit concept, some motifs conjure Eastern music and Chinese or Japanese sounds and melodies. I'm curious about this record, again, noting some of the song titles. There's this feeling of space and time or distance and movement. Am I onto a concept there?

Greg: I didn't have a concept. It's funny that "The Illusion of Depth"—I was in an art supply store and looking through some books on how to draw. I found this chapter called "The Illusion of Depth,” where you use shadows. So I pulled out my phone and threw that in my notes. "Finding the Future" was one of those songs where I just had to close my eyes and let the music speak to me and inform my imagination to come up with an idea.

Lawrence: Do you present this music live?

Greg: I would love to, but I don’t have a way to do it. So, right now, it's just kind of a studio project. I have another record, an addendum to Underwater Detection Method,, ready to go. I just need to get the drums on it, get my bass, get the guitar, and mix it. It touches on electronic subgenres I didn't touch off on this record. This new record has some stuff that sounds a little more industrial, a little more gothy—I don't know if goth is the right word, but a little darker.

Lawrence: Might be right for our times.

Greg: Yeah. (laughter) Exactly. Oh, just in time. 2025.

Lawrence: Yeah, thanks, Greg. The soundtrack to 2025. (laughter)

Greg: That's where I'm at right now. I would love to finish this record and get it out this year. I'm trying to get on a program where I can make a record and release it every year, as close as I can. But all this time, from when I did Songs from the Imperial Garden and then doing Underwater Detection Method, making that, learning all the stuff—I just spent so much time learning. I'm still always learning, but now I have a pretty good idea of what I'm doing and how to do it. So now I feel like I can start moving forward.

Lawrence: Yeah. I think people don't realize, or certainly listeners may not realize, that in addition to learning the tool and writing the songs, there's also the workflow component. There's a production element that has to be thought through.

Greg: Absolutely, and often nothing happens when you sit down and work. You just have to constantly be doing it to find or get things you like.

Visit Greg Lisher online at greglisher.com and follow him on Facebook and Bluesky. Purchase Greg Lisher's Underwater Detection Method from Bandcamp or Qobuz and listen on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

Comments