• Worked with Pauline Olilveros, Mark Dresser, John Oswald, Evan Parker, Uri Caine, Peggy Lee, and other creative music luminaries

• Creator of Kenaxis, a widely used software platform for electronic musicians

• Teaches sound design at Simon Fraser University

• Website | Bandcamp | Kenaxis

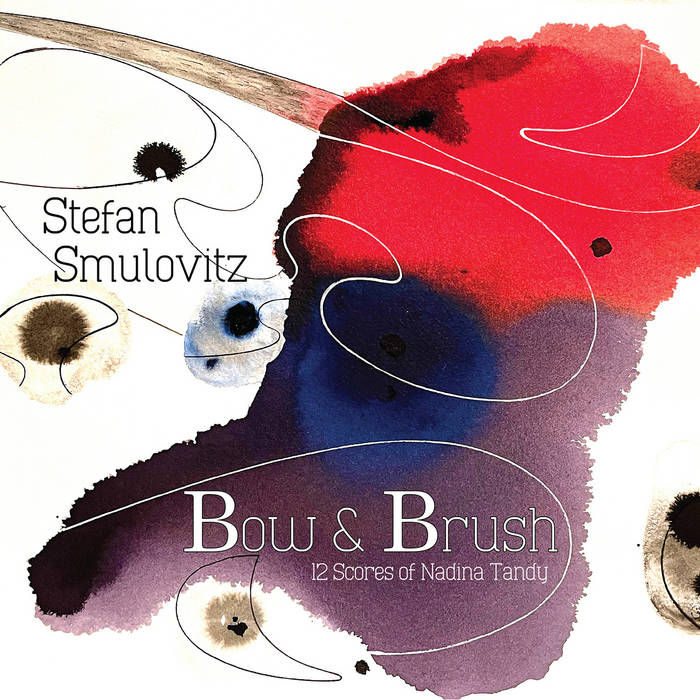

Stefan Smulovitz's journey from biochemistry student to innovative musician embodies the intersection of scientific curiosity and artistic expression. In this wide-ranging conversation, Stefan discusses his latest album—a collaboration with visual artist Nadina Tandy—and details how his background in science influences his approach to music, his pioneering work with the Kenaxis software, and his philosophy on artistic creation.

Currently residing in Roberts Creek, British Columbia, Smulovitz has carved out a unique space in the experimental music scene, blending acoustic instruments with electronic processing and live improvisation. He works in live film soundtracks, dance scores, and multimedia collaborations, all unified by a deep appreciation for the organic imperfections that make art human.

Lawrence Peryer: Your background in biochemistry is intriguing. How do you see the connection between your scientific studies and your music?

Stefan Smulovitz: I think what's there for me is wanting to understand things deeply and find the resonances of how things work. When you start understanding how things work, this beautiful little vibration happens—you think, "Oh, I get it. That's how that thing works."

What's great about sound and music is it's an endless mystery. So is biochemistry and science. They haven't figured everything out, but that's the part I love—there's always more to discover and discover. I guess it's that curiosity that drives me in both directions.

Lawrence: It reminds me of how religion, philosophy, and psychology are different modalities of figuring out the human condition and the nature of reality.

Stefan: Absolutely, and music is just doing it non-verbally. I love vibrations and feelings. Listening is a big part of music—that feedback loop of figuring out how things work. That's also what science and philosophy are—you're searching for how to make sense of things.

Through music, I'm trying to make sense of how I feel, how it resonates with the world, what I put out, and how it moves other people. That connection is really important to me. It's not just about some kind of pop song; I play much more with sound. There's some kind of physicality there that's similar for me.

Lawrence: How did your collaboration with visual artist Nadina Tandy come about?

Stefan: One of the most important concerts I ever saw was Bill Frisell playing a live soundtrack to a Buster Keaton film. After that, I started doing live soundtracks for films, and I've now done over a hundred live soundtracks for different movies. I had a band called Eye of Newt, and we'd do all these live soundtracks.

There was something about being in conversation with those images that created this structure. It allowed freedom of expression but also provided constraints because you're interacting with the film—you're conversing with it, so you can't just do whatever you want.

Each collaboration I do pulls something different out of me, and that's what I like—it doesn't let me fall into my patterns. Working with an artist and doing scores isn't the first time I've done that, but I enjoy that it forces me to pull something different out. Particularly, that first score, "The Pier," that I did with Nadina captured something that felt like being here at home in Roberts Creek, where I had just moved when that first piece happened.

Lawrence: When working on an individual track, did you have the painting with you?

Stefan: Yes, I had the originals and would put them up in front of me. I would look for structural elements. For instance, "The Pier" is obvious—there are these gong hits, and if you look at the painting, these little round things are connected to the gong hits. Every time one of these little circles appears, there will be a gong hit.

I try to find a few structural elements with each painting that would delineate some time progression. Then, I would take the emotional feeling it gave me and maybe do a melody based on that. The first thing I would look for is what I see structurally that I would like to use to outline my composition. I'd record that first to have a timeline base, and then once I had that structure, I could figure out what I would do with everything else.

Lawrence: The duration of the tracks is all fairly constrained within this three to four-minute construct. Was this a deliberate choice?

Stefan: It was intentional. I've had this thing in my head for a while: if you leave people wanting more, it's a beautiful feeling. If you're satisfied, gorge yourself; afterward, you're finished. Length is not a problem—on Sunday, I'm doing a show with a shakuhachi player where we'll play for 90 minutes straight. But actually, being shorter and more concise is more of a challenge.

I wanted these little vignettes where you just enter this world, get a sense of it, and then move on to the next one. I'd love to present this in a gallery setting, hopefully at the Sechelt Art Gallery, where we set up 12 music stands with the paintings and lights illuminating each piece as its corresponding music plays. What I like about that idea is that visual art is usually not time-based, and this makes it time-based, encouraging people to spend more time with each piece.

Lawrence: Do you have hopes for how your listeners might approach the album? Do you want them to have the visual works in front of them?

Stefan: When I made the CD, I included a booklet with all the paintings because I think the artwork is an integral part. It changes how you experience the album when you look at the images. I might also release a version on YouTube where people can experience the music with the synchronized images.

But I'm also happy if it inspires people to create visual responses. That's the thing about art—it doesn't have to be limited to the source. I watched a documentary about Bill Viola, and someone asked him why he makes art. His answer was "to inspire others." I thought that's the best answer I've ever heard.

As an artist, I think it's important not to get stuck in just one kind of art. I love collaborating with dancers, theater artists, filmmakers, and visual artists. You get different perspectives on things. It expands your palette in your art form to experience other art forms. If anyone sees this piece and it inspires them to work with art in any way, that makes me happy.

Stefan Smulovitz's latest album, featuring visual artwork by Nadina Tandy, is available now on Redshift Records.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments