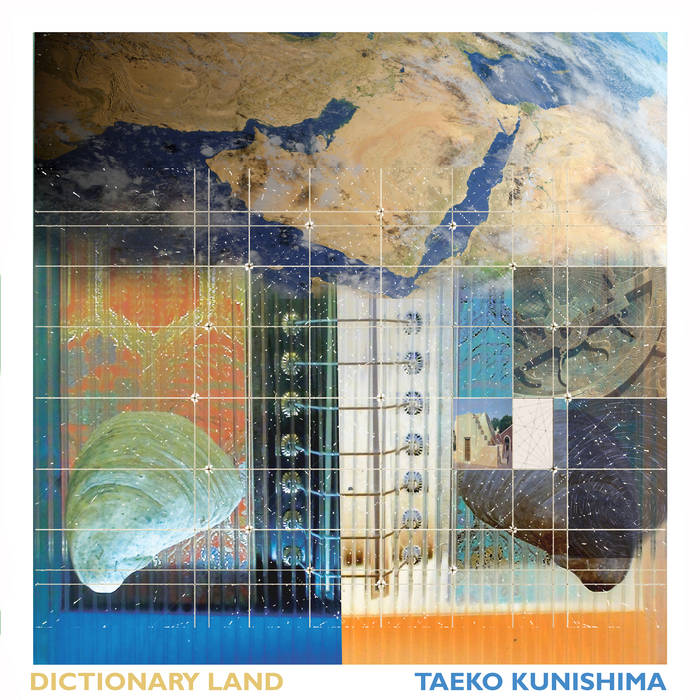

Taeko Kunishima is a pianist and composer who I first became aware of in 2011, around the release of her third album, Late Autumn. At the time, I reviewed that record for the website All About Jazz and have followed her music since.

While new music from this compelling artist is released somewhat sporadically, it is always worth the wait. Takeo Kunishima makes music both complex and accessible, conveying many moods and reflective of the world around her.

It is with great joy that we bring you this long distance, conducted-by-email discussion with Taeko Kunishima.

Lawrence Peryer: Writings about you often reference the “life-changing” experience you had when you encountered the music of Miles Davis, but there is never any elaboration. Do you recall which of his music you first heard? Could you describe the impact - specifically or even more broadly - that it had on you first as a listener, and then as an artist?

Taeko Kunishima: When I first heard Miles Davis’s music, I was studying Classical music and I didn’t know much about jazz. My father died when I was two years old, but I remember that his violin was lying on his study desk, near a picture of Rodin’s The Thinker, his English and Japanese books lining the shelves. I heard that he loved to listen to Classical music, and he took my mother to a classical concert. He didn’t influence me directly, but somehow, I was influenced indirectly. I loved listening to Classical music, and I read his books.

Listening to the Miles tune was really stimulating. I know it was Miles Davis because the radio presenter said that, but I missed the title.

When I look back, or I try to think of the moment when I heard his music, I thought it sounded very spacey and very mysterious, I almost felt I was in a dark universe. I think it must have been modal jazz, such as Kind of Blue. At that time my taste in music was from the Classical period to the Impressionist and beyond, such as Debussy, Takemitsu and Schoenberg.

LP: “A dark universe” …such a fascinating way to describe an encounter with his music, yet one that I instantly understand and suspect other listeners of his would as well. Amazing.

Was there anything in the Classical music you were listening to that prepared or opened your ears to be able to take in Jazz? I ask because my first encounter with serious or challenging jazz was John Coltrane’s Africa/Brass. I did not “get it” at first but it came highly recommended, so I kept revisiting it until it made sense. I have also observed other listeners as their ability to absorb and enjoy Jazz blossomed. The ear needs to learn to hear it.

TK: In the Impressionist work of Debussy and the work of Messiaen we can see various approaches to musical modes. Debussy composed the Engulfed Cathedral piano prelude(Book 1) in which he uses the pentatonic scale, whole tone scale and modal approach scales such as the Lydian and Mixolydian. With Messiaen there is a modal scale he devised himself, which I used in a piece on Dictionary Land.

LP: Where would a listener hear your classical music background in the music you make today? How do your classical music studies manifest in your current work? Might there be specific examples you could point to in your work?

TK: Classical music was sometimes a source of musical approach for my compositions. For example: ‘La Mer et La Rose’ from my latest album Dictionary Land, you might recognize Debussy’s harmony, using augmented chords and whole tone scales quite frequently.

I still listen to Miles a lot and modal jazz is very influential in my compositions. On the current album, the improvisation sections are modal in approach.

LP: I hear elements of the “dark universe” you mentioned in your music, particularly the music on Dictionary Land. Not in any way stylistically similar to Miles Davis, more in the mood or tone conjured for me. Now that you have planted that phrase in my head, I find it sticks!

Your music breaths in a way that I find very inviting. Could you tell me a little bit about what role space and silence plays in your compositions and improvisations?

TK: Japanese concept of 間 (Ma) is something that relates to all aspect of life. It has been described as a pause in time, or interval, or emptiness in space. Noh theatre(能)is a supreme artistic expression of Ma, the dynamic balance between object and space, action and inaction, sound and silent, movement and rest.

You see Ma in Japanese music, culture, architecture, and everyday life. Toru Takemitsu was interested in Japanese concept of ‘Ma’ pause or space.

The track ‘La Mer et La Rose’ from the album Dictionary Land has a pause between two different passages, and the track ‘Dialogue with Solitude’; has an ‘intense’ interest in the concept of Ma which made for atmospheric, intense moments of silence, as occurs in dialogues with solitude.

LP: How important is live performance in your work? Are you content to compose and record or do you want to present the music live?

TK: The ideal situation is the sequence: compose, record, live performance. The live performance is good way to let people to know about my music, and sometimes you build good relationship with the fans.

We don’t know what is waiting for us in the ‘dark corner’ of life. After I recorded the album Dictionary Land, my hand arthritis soon developed, which caused pain and stiffness, especially in my right hand. I am finding a way to adapt to new physical conditions. I must change my composition style, and not rely too much on some types of piano performance. I started writing new material which uses new compositional tools such as sampled sound, electronic sound, more field recordings combining with acoustic sound.

LP: I was not previously aware of your experience with your physical condition. Were you quick to embrace the challenges the arthritis posed to your piano playing or did you need to find acceptance? At risk of being insensitive to your experience in particular, I would comment more generally that creativity and ingenuity often result when the artistic temperament is met with limitations in its tools, physical capabilities, etc. Do you approach this next stage of your development with anything like enthusiasm or excitement to see how your creativity manifests?

TK: I can’t see any benefit to have my currently limited physical condition for my creativity or my musical career at this moment. However, I am trying a different approach for my composition for cope with the limitation, to use sampled sounds, field recordings, analogue electronic sound combined with acoustic sound. With this approach the music can possibly be gentler. I have to see whether there is a benefit to my handicap by completing a new project, then seeing the listener’s reaction.

LP: Your engagement with the broader world encompasses an awareness and integration of society’s challenges: violent conflict, environmental catastrophe, the political turbulence we see all over. As an artist, do you feel an obligation or responsibility to reflect these issues in your work? Is it even a choice, or more like something you feel compelled to do?

TK: I am just average person who is interested in current political events, and the violent conflicts and environmental climate change generally.

I was aware of the civil war in Yemen, but you hear more and more news about it now, I started to feel very overwhelmed. Someone said because I lived in Yemen once, I can feel the people’s situation, and can become very emotional, which could be partly true. I started to follow the people who are concerned about this and those who are more sympathetic to Yemeni people generally, on Twitter.

I think the people who live there want to have peace and are not interested in the proxy war.

In Sana’a, where I once lived for a year, a long time before the war, the Houti took over, and they suffered due to the Saudi coalition constantly air striking children’s schools, hospitals, civilian areas, and the linked distant seaports. Yemeni children are suffering with malnutrition and hunger. Beautiful ancient buildings were destroyed. There is always relationship between human rights and conflict. I thought from the human rights point of view, I would like to send the message against war and in favour peace by reflecting the mood of the impact of war, using music.

A ceasefire agreement was announced very recently, partly influenced by China, however not all sides have confirmed the ceasefire, but prisoners have been exchanged.

LP: How did you come to identify with or be moved by the notion of displacement or conflict? Was Fukushima a moment of awakening for you or were you always so aware?

TK: I understand some of the feelings evoked by displacement from the time immediately after leaving the Middle East and arriving in London, not knowing anybody. As for conflict and the history of almost perpetual conflict somewhere in Yemen, it has been at the crossroads of different civilisations for three thousand years. In its recent form it has been described as the most fragile state on Earth, with depleted aquifers. To some extent the form and locations of the lands on Earth have an influence on their history: compare the eras of isolation in Japan to the disrupted lives at the crossroads at the south of the Arabian Peninsula.

The Fukushima earthquake and tsunami caused the nuclear disaster. This incident made me more aware of nuclear disarmament, and the anti-nuclear stance. It also made me think about how to deal with nuclear waste, an environmental issue. We are all aware of climate change. If you used oil, gas, or coal instead of nuclear power, then that creates more CO2. It is not a simple question, especially for Japan where there are fault lines everywhere, some by the nuclear plants.

I wasn’t in Japan when it happened, but it made me more aware of environmental issues.

LP: Can you talk about how the absence from musical activity that you experienced while living in the Middle East impacted your development as an artist? Was it a welcome break? Were there any benefits to having a break?

TK: I had musical career absence when I was in Middle East and few more years after I left the Middle East and moved into London, where I had never lived before. I didn’t know anybody, and I felt I was as if I was a refugee. It took some time to settle down there. I had culture shock when I arrived in Yemen from Tokyo, like a city girl lost in an ancient, primitive Arabic culture, who could not speak any Arabic, and my English was pretty bad. You can pick up a strange disease there, expatriates called it ‘Sana’a disease’. You only get an appetite by eating Yemeni curry every day. However, you never get bored. People normally say areas such as Oman, Bahrain or Dubai are quite civilized, but they are very boring places to live, this was not the case in Yemen. I was too busy surviving and did not have any space in my mind to think about discovering more about Yemeni music and playing with Yemeni musicians. I really regret it now, but my living memory of the Middle East gave me a benefit; to motivate me to compose music, based on my experience of living in the Middle East.

LP: How did your creativity manifest during that period, if at all?

TK: Unfortunately, I was too busy trying to survive there, so musical creation came after the experience from that time. Some of inspiration to write some of the tracks in Dictionary Land came from another source. The title Dictionary Land refers to the title of a book about the highly complex and contradictory language and culture of Yemen by Tim Mackintosh Smith, who is fluent in Arabic.

LP: These details of your experience cause me to hear Dictionary Land in a new, more meaning-filled way. I feel as though, as a listener, I am witnessing the integration of your experiences and the maybe even the experiences you missed out on. It is really a wonderful and unique collection of music. Thank you for agreeing to this conversation. I look forward to hearing where your music goes next.

TK: Thank you very much for asking me for this interview and thank you for having me.

I really appreciate your thoughtful comment about Dictionary Land.

I hope this interview improves the chances of gaining new listeners for my music, and lets people get to know a bit more about me.

Hopefully we will not have to wait too long for my next album.

###

Please explore Taeko Kunishima’s music on her official website, which includes links to her music on platforms worldwide, notably Bandcamp which contains her full discography.

Comments