Taylor Deupree, through his influential label 12k, did his part to help define the minimalist electronic music movement of the late '90s and early 2000s, while Joseph Branciforte's more recently established greyfade imprint has gained notice in pushing for high-resolution digital releases and intricate documentation of experimental music. The two music producers and label dons (among other artistic hats) are aligned philosophically in their meticulous approach to sound, visual presentation, and curatorial vision. Deupree and Branciforte are also enthusiastic fans of each others' work.

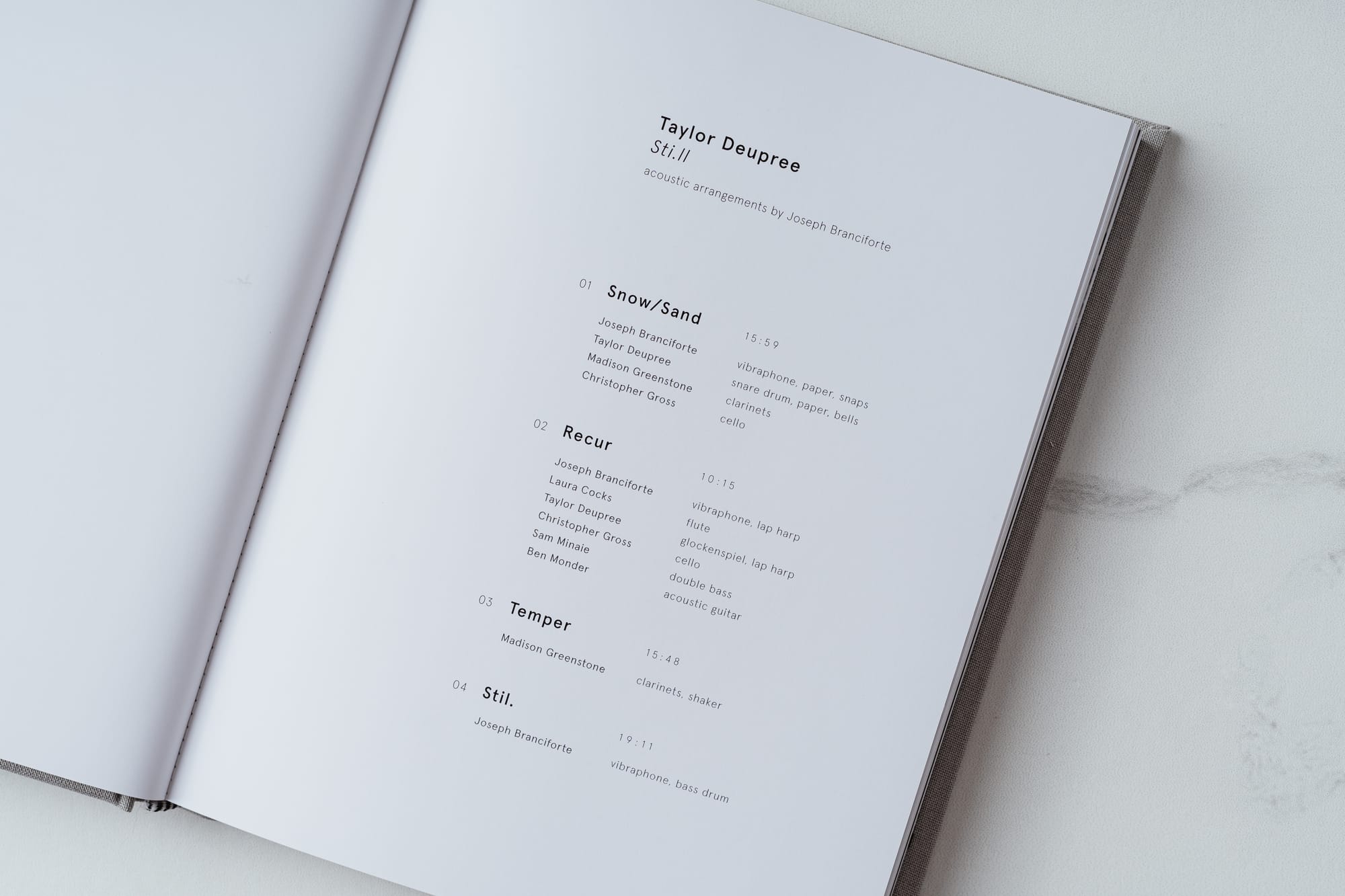

On the 2002 album Stil., Taylor Deupree, inspired by photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto's Seascapes series, built four pieces based on the complex repetition of looping passages. The album notes state, "The underlying idea is that a pattern repeated for long enough begins to reveal hidden pulses and movements not initially apparent." In other words, repetition is a form of change.

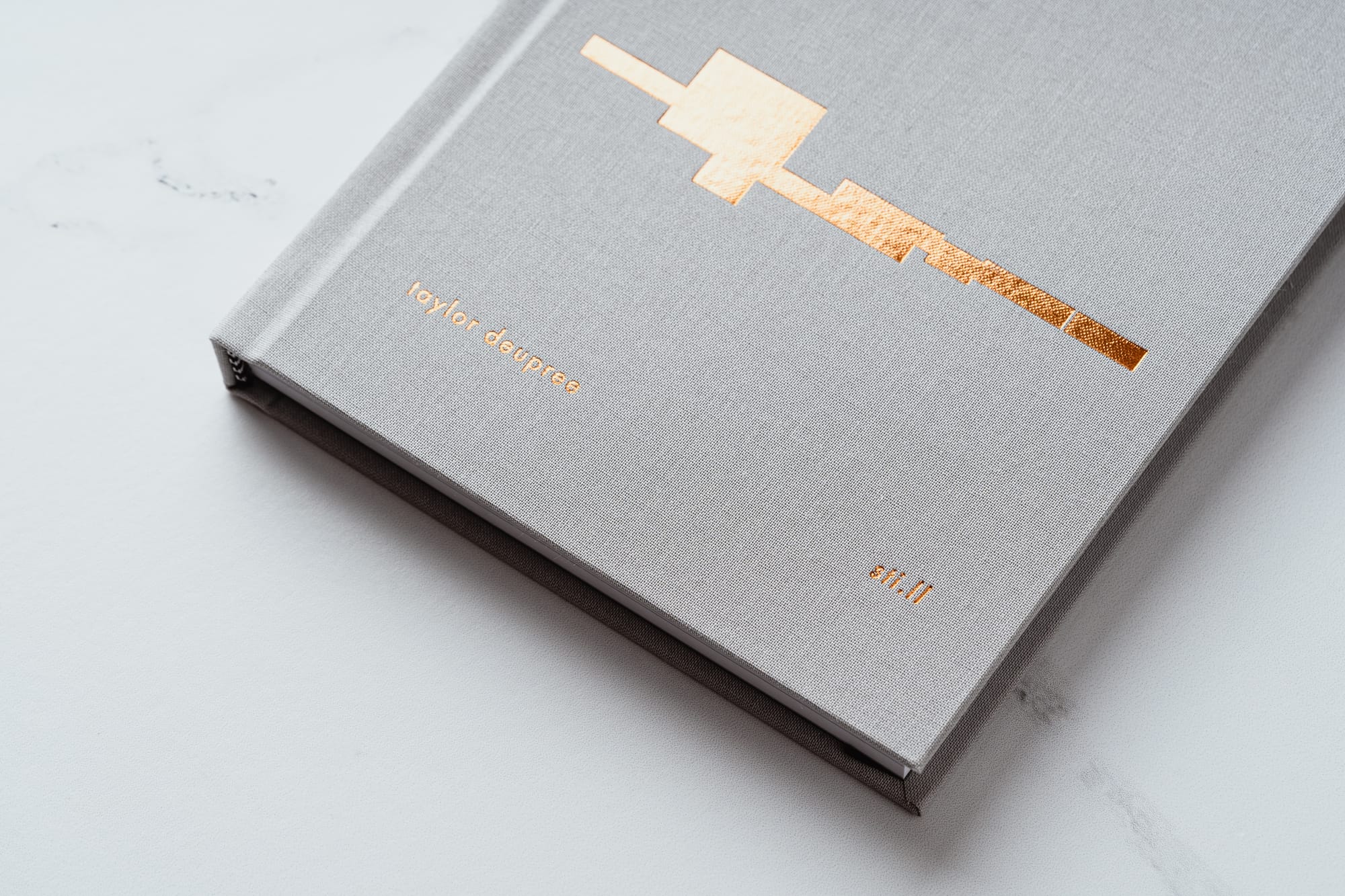

Two decades later, Deupree enlisted Branciforte for a radical 'reimagining' of Stil. As Branciforte is known for his innovative approach to mixing and production, particularly in integrating electronic elements with acoustic instruments in experimental music contexts, the plan was an acoustic transformation of the album. The process required technical rigor—adhering to a strict "microphones only" recording philosophy—and artistic liberty, balancing fidelity to the source material with the need to create something that could stand independently. The result, titled Sti.ll, is quite possibly a masterpiece that will endure alongside its original album inspiration.

Lawrence Peryer spoke to Taylor Deupree and Joseph Branciforte about this fascinating and ambitious project on a recent episode of the Spotlight On podcast. What emerges in the conversation is a deep consideration of how musical art can be documented, presented, and contextualized in the digital age. Their discussion reveals how both multi-hyphenated artists have cultivated distinct aesthetic ecosystems that extend beyond sound to encompass visual identity, presentation, and philosophical approach—creating what Branciforte describes as "small universes that you can get lost in." The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Achieving the Impossible

Lawrence Peryer: I've been immersed in the world of sti.ll for the last few days. To a large extent, I think that speaks to the success of the music and the format. There's been so much to take in—the backstory and the FOLIO element create a universe to get lost in as a listener.

Joseph Branciforte: That's great to hear. We put a lot of work into it—the music was its journey, but it's nice to hear that the book has also resonated.

Taylor Deupree: I agree; it's made so much to talk about and many angles from which people can come. From now on, every other release is going to pale in comparison.

When we started, I remember Joe saying, "We've gone this far. We're going all in." I don't think we knew what it would be like when we started. At the very least, we knew it would be some sort of digital streaming release. When Joe started doing the FOLIOs, the first one with Kenneth Kirschner, this was just sort of a natural fit for that.

Lawrence: As I was reading some other things about the album, the last sentence of the Pitchfork review kind of leaped off the page at me. The sentence says, "Sometimes, if you shoot to do the impossible, you actually achieve it." Reading quotes from you both, I see there were various stages where you wondered if it was achievable.

Joseph: I was not convinced we could pull it off. Taylor proposed the initial seed of this whole idea, and the record we are reimagining is his work. So, to a large extent, Taylor defined and imagined the parameters, but from my perspective, there was a murkiness in the beginning.

I was such a fan of the original stil. album, the electronic version from 2002. I think the Pitchfork review hinted at the idea that one could do such a great job with a translation like this, but it will always be compared to that original. In a way, it can't fully stand on its own. So there's this kind of shadow hanging over it where you're not making a fresh work; you're making something that will be compared. People will listen to them back to back and try to compare and say, "Oh, well, how did they do this? And how did they do that?"

Usually, when you make a record, it's fresh terrain, and you're out in the open. As I mentioned in the book, I had doubts about it from that perspective. But ultimately, as we started getting into it, just musically, it began to become its own thing. I became convinced that not only was it worth doing in an academic sense but that, sonically, we were getting somewhere that was new and exciting.

Lawrence: Were you aware of other projects where an artist revisited an early work in such a dramatic fashion?

Taylor: The first thing that comes to mind is William Basinski's works. They've done Disintegration Loops with a large ensemble. I don't think there's a recording beyond a live recording. I know that Sigur Rós have been recently working with a big orchestra, redoing some of their music.

Going back to the previous question, I had no idea how deep we'd go with it when I set out to do this. My initial experiments were just with a xylophone and an electric piano. I probably would have been happy if we ended up just going by ear and recreating them with a new set of instruments.

When I handed it off to Joe, he came back with a three-minute demo and showed me the scores, and I was blown away. I had no idea he would somehow pick these abstract pieces apart, note by note and frequency by frequency, and reconstruct them with so much detail. As soon as we had those initial scores done and that initial five-minute piece with the clarinetist, that's when it clicked.

The Record is a Record

Lawrence: The FOLIO essays revealed that you had two rules or governing principles when you went into this: one is the idea of everything being recorded with microphones, nothing plugged into a desk or a computer. The other was that you would allow some changes. There wasn't this idea that you were fetishizing the original. It's fascinating that ability to give yourself the room, not to have to be so beholden to the original while still having its essence, but then this aspect of Joe going in deep with the fidelity of the recordings. There's a little tension in all those elements.

Joseph: A neat way to explain that would be that I was more the fidelity guy, and Taylor was more like, "Let's loosen this up." That's a simplification, but in a sense, I came to it as a fan of the original album. I didn't want to do a disservice where it was like, "It's a couple of notes from the original release, and we just jam on it for twenty minutes, and it's vaguely the same."

I was interested in getting to the essence of the original pieces' structure. This transcended the idea of pitch collections or anything like that. I was more interested in the specific interactions between timbre, spectrum, and form, with repetition and different loops repeated over one another in various lengths.

Something about the structure made the original record successful. In conceptualizing how to achieve this acoustically, I was adamant that I didn't want to lose those aspects. We can create an ambient record with acoustic instruments, and that's fine. That can be beautiful, but I don't know if it's what makes stil. the original stil., what gives it its identity.

I learned at the end that the best way to celebrate the original is to allow this one to be its own thing because otherwise, it does become a simulacrum. And I think we wanted this to stand independently at the end of the day. So, hopefully, it walks that line.

Lawrence: In one of the essays, the use of microphones was referred to as a concession because the microphone itself is electronic. Do you see a world where you could present this music in an environment without amplification?

Joseph: I can think of a few of these pieces that should work well, just acoustic without amplification. But Taylor would probably agree with me that the record is a record. A live performance was not what we were after, and we weren't thinking of it as performable. It was more like making a new tapestry.

Ultimately, I'm a recording engineer, and I think of the microphone as an instrument in its own right. The mic placement and how we captured these sounds were done with specificity. That's part of what makes this sound like it does, so I don't know if it would work as a live thing. It probably would, but I'm happy with the recorded work.

Taylor: I think it would be possible—we would need a lot of players. Sometimes, fifteen clarinet layers are going on at once, added in post-production. Madison Greenstone, our clarinetist, is not performing the entire song in one take. It's fifteen or so layers of different clarinet pitches, with difficult breathing and mouth techniques.

Parallel Inspirations

Lawrence: I wonder, in the early '90s, where you were as a musician and a listener? Were you already hyper-aware of minimalist players and composers?

Taylor: I was very much into minimalism but less so musically. I didn't listen to many classic minimalists or composers, such as Philip Glass or Steve Reich, and I still haven't. My musical minimalism came more from Brian Eno and my contemporaries. I always thought of my minimalism more in a quiet sense than necessarily a structural sense.

My interest in minimalism came from visual art and architecture. I was looking at a lot of minimalist architecture, Tadao Ando in particular, Donald Judd's sculpture, and that classic sort of minimalist school of visual art was influential to me. I was more interested in ensuring that non-musical artists' sources influenced my music than musical sources. Stil. in particular, was very much influenced by the Seascapes photographs by Hiroshi Sugimoto.

If another musician influences me, I would try to sound like that musician, and I don't want to do that. So, I translated visual minimalism into music and still do it.

Joseph: I was always a big fan of Taylor's 12k label, its visual aesthetics, and the kind of graphic design he has been doing. Taylor hit on this idea that a lot of the inspiration for this kind of music can come from visual art, and even for me, graphic design is a big sort of parallel inspiration.

Sometimes, I find it odd that I am a musician. Even though I work on music twelve-plus hours a day, it doesn't feel like a deep part of my identity. Music feels more like an extension of my interest in attention, focus, and problem-solving.

I think this aesthetic can transcend mediums. The idea that it's manifested in sound to me sometimes almost feels sort of arbitrary. It could be food, or it could be looking at nature, or it could be visual art, or designing your home, or different materials that you might choose to have in your kitchen or something. If you have that intentional, thoughtful process, it almost feels that that's where the music stems from. The fact that it's sound is not necessarily essential.

Remain Here and Be Comfortable

Lawrence: There's such an intentionality and integration of those other forms, obviously the design aesthetic. If you go to your labels' Bandcamp pages, you can see the thumbnails of all the albums next to each other. Don't scold me for saying it this way; you get a sense of the brand identity. You can feel the context.

Taylor: You don't have to apologize for the term "brand." When I started 12k, branding was hugely important. We're not talking about a big corporate brand here, but when I began advertising the label, I'd do magazine and print ads and things like that back in the day. I was always advertising the label, not individual releases.

I was hammering home the label aesthetic, the idea that if you like one release on the label, you'll probably like all of them. So, it was about a visual identity and a sonic identity. I don't think branding in that sense is a bad word or has to be a bad word, especially when you're on our scale.

I felt it was easier to have a label where things were a little more under control than to have every release be different. Some labels do that, and the big ones do that, which can be great. But when you're a one-person operation, honing in on a design template for the releases and getting everything down to a science helps the workflow. Consequently, it helps the identity and gives a brand, a family, and an aesthetic.

Joseph: When you're randomly browsing the internet, you're bombarded with all these out-of-context pieces of information, whether it be music, news articles, photos, design blogs, or whatever comes across your feed. Finding a website with this sense of order, coherence, and curation is nice. It's relieving, and it's almost like I feel I can take a breath. There's thought and intentional structure to this and so much to dig into. I can just remain here and be comfortable. It's almost meditative.

We're talking about design choices, web design, and stuff like that, but I think it's on a larger level. We're talking about unity in thought. I'm always trying to integrate these components into something coherent, so there is much to dig into. Not everyone will engage on that deep level, and that's okay, too. If they just enjoy the music, that's great, but I like the idea that there's this kind of small universe that you can get lost in. With Taylor's label and, hopefully, the type of stuff I'm trying to build with greyfade, you can sort of get into it and nerd out a bit.

Lawrence: It's sort of the best of what a brand can be, which is that if you go there, you may not love everything equally that comes from a label, but you can trust that it's going to be interesting or earnest or within a certain genre or whatever the association is. It's nice to have those shorthands, even more so in this world where it's tough to know where to begin.

Taylor: Small labels like ours serve as curators. There are so many great little labels out there that are consistent. And generally, if you like one of the releases, as you said, you may not love them all, but at least you sort of know what you're getting into. Then, you can start rabbit-holing it from there, following an individual artist's path through other labels. Joe and I use this idea to make sense and to organize the craziness entailed with running labels and doing everything else we do.

Joseph: The more I run a label, the more I recognize how difficult and special it is to maintain consistency, like how Taylor's done or a label like ECM. It feels like all the forces are conspiring to prevent that from continuing.

I don't even mean it in some conspiratorial way, but I get so many demos of music where I'm like, "Man, this is great. It has nothing to do with what I'm putting out, but it's amazing." And I'm often tempted to broaden the scope of this to become something wide-ranging, but I've resisted that. It's a question I struggle with sometimes because the music I'm putting out on greyfade is a very small sliver of the music I'm interested in as a listener.

Taylor: Some advice to your young label from my old label is something I've done several times: throw a curveball out there occasionally. The first curveball I remember throwing was the CD by Christopher Willits called Folding, and the Tea. Chris is an ambient artist who uses guitar as his main instrument. You have never heard the strum of a guitar on a 12k record since its inception, and we very specifically started his album with the strum of a guitar. I said, "I want to start with this piece because people will be confused when they put the CD on." That sort of launched a whole thing into guitar music for me.

That album wasn't such a curveball, but I released music from Scottish singer-songwriter Gareth Dickson. And this is a straight-up singer-songwriter—acoustic guitar, vocals, that's it. There's nothing like that on the label, and it is an anomaly. I just love his music. And when you listen to it, you're like, "This kind of works in a weird way." You can be into stil. or Chris Willits's music or any of the music on 12k, and you'd probably put on Gareth Dixon and like it. It has qualities I'm looking for in quietness.

It is easy to get stuck in a genericness, like, "Oh, it's another 12k thing. it's just the same." The label has been running since '97, and I always struggle with that. How do I not just keep doing the same thing, release after release? Sometimes, these curveballs are just weird little curveballs; sometimes, they open up a whole thing for you. You must stay willing to accept changes and just go with the flow.

Visit Taylor Deupree and 12k at 12k.com and follow him on Instagram and Facebook. Visit Joseph Branciforte and greyfade at greyfade.com and follow him on Instagram, Threads, and YouTube. Purchase Stil. from 12k, Qobuz, or Bandcamp, and listen on your streaming platform of choice. Purchase Sti.ll from greyfade, 12k, Qobuz, Bandcamp, and listen on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments