We've been doing this once a year for several years, and the pattern is well-established. The kids are all asleep in the cabins, and the more sensible adults are too. Only a few of us are up late, sitting around the campfire, watching the flames, and passing a bottle around.

It's Irish whiskey, brought by one of our friends who moved here from Northern Ireland. Their family is Catholic, and so is the whiskey. It's from the Powers distillery. The other friend from Northern Ireland also drinks it, although they are Protestant, and Jameson is the Protestant whiskey.

They are roughly my age, which means they were born into the sectarian violence known as the Troubles and, both being from the Belfast region, were surrounded by some of the worst of it until they moved away. I've listened to them talk a lot on these camping trips and learned just how deep these divisions are where they came from.

It's not just the whiskey. There's a Catholic version of everything and a Protestant version as well. They say they wouldn't have been friends there simply because they never would have met in daily life. They lived in Catholic areas or Protestant areas, went to Catholic schools or Protestant schools, and shopped at Catholic stores or Protestant stores.

When one of them goes back for a visit, they always return with an enormous box filled with bags of Taytos brand crisps. These are the best potato chips I've ever had. Someday, I want to visit the Taytos Theme Park near Dublin. That's where the company that makes the Catholic Taytos—the "Free Staytos"—is. Even our Protestant friend agrees they are better than the Protestant Taytos, made by a different company with the same name in Northern Ireland.

Well into episode two of the 2023 five-part documentary series Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland, a voice we haven't heard before begins to speak.

There are places in Belfast where things have happened in my life that I feel very uncomfortable walking past, like Direct Wine Sales is in the old building where I used to work for Kodak, and I came out one night, and three gunmen tried to grab me in the car, and these two guys, they jumped in and saved my life, and I managed to get away.

That had happened to friends of mine, and they weren't seen again.

They were tortured.

I just thought, "Well, I'm gonna do something that I really want to do before they kill me," and that was when I decided I was gonna set up a record shop.

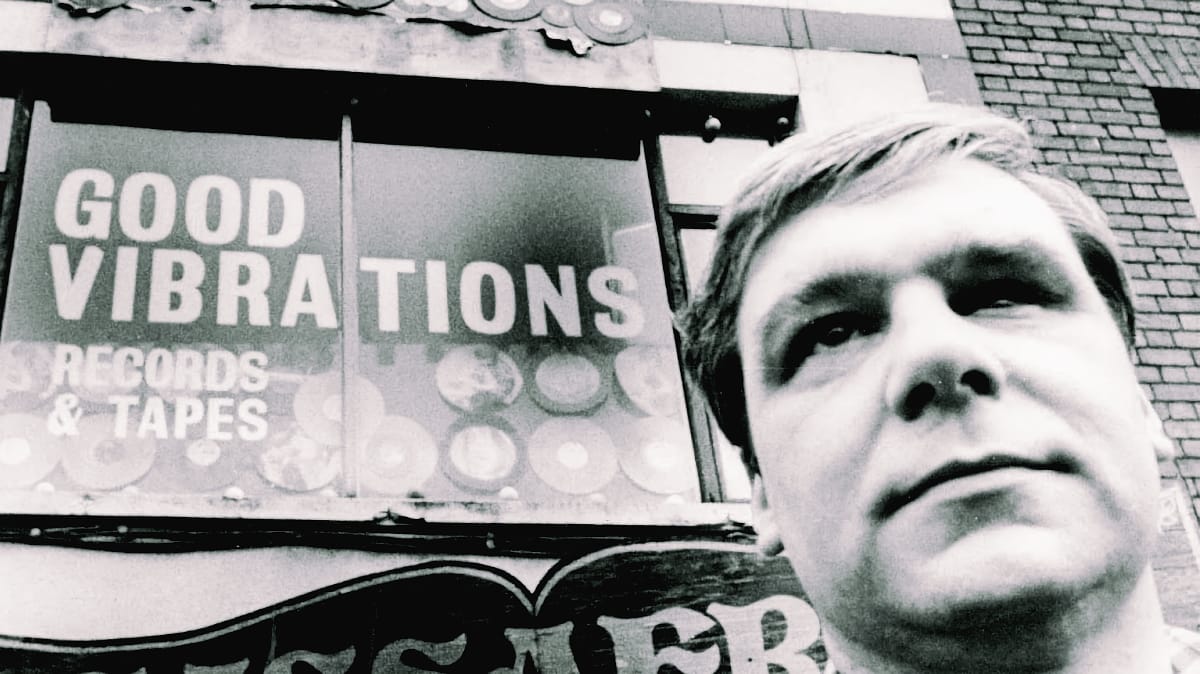

That's Terri Hooley talking. He opened his shop in late 1976 on the street nicknamed "Bomb Alley." A block away, the Europa Hotel was bombed thirty-six times between 1971 and 1993.

This campfire burned a decade before that documentary came out, and I'd never heard of Terri Hooley. One of the friends has musical taste that overlaps with mine, and we've talked a lot about bands they saw when living in Manchester and London, but we've never talked about the music scene in Belfast. I know a couple of Northern Irish punk bands and have a vague knowledge of the Troubles, but I don't know much about the music scene there.

That's about to change. One of my friends turns to the other.

"Did you see 'Good Vibrations' yet?"

"I have. It's bloody good, isn't it?"

"They did such a good job. Everything looked exactly like it did."

I take another pull off the bottle as it comes around, and then I sit listening.

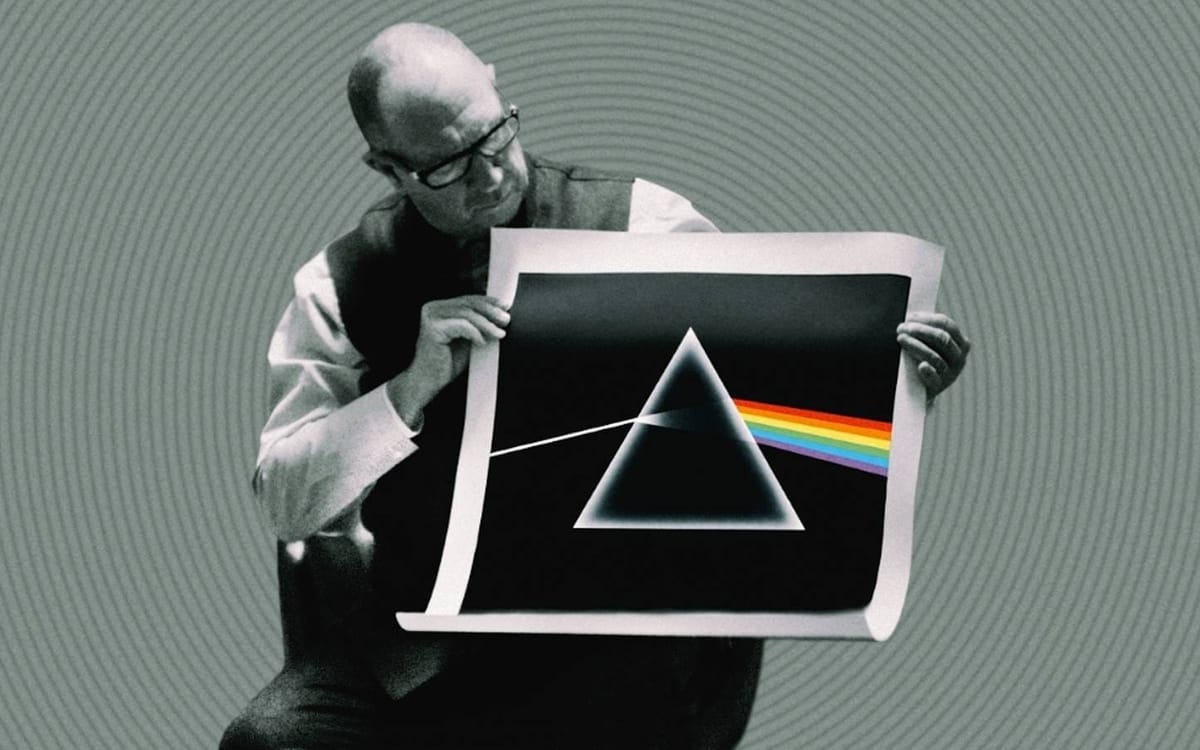

The 2013 film Good Vibrations tells what Terri Hooley calls a "really very accurate" version of what happened in his life after he opened that record shop. A title card at the start of the film phrases it as "Based on the true stories of Terri Hooley." Those stories had been told three years earlier in Hooley's book Hooleygan: Music, Mayhem, Good Vibrations.

The thing is, my friends weren't talking about the film, even though they were talking about the film. They were talking about their lives. And their lives are really what Terri Hooley's stories are all about.

"My parents would've had a fit if they knew I was going down to Great Victoria Street."

"So close to the Europa. But it was a great record store."

Hooley didn't open a sectarian record store. It wasn't just for Protestants or Catholics. It was for everyone. The only problem was that he opened his record store exactly at the moment an earthquake hit UK music.

The first wave of UK punk lifted and codified elements from New York's far more diverse scene. The perfect vehicle for expressing anger and frustration in a seemingly rudderless nation with a stumbling economy turned out to be playing like the Ramones while dressing like Richard Hell. But what Hooley loved was Hank Williams and the Shangri-Las.

Online reviewers love to describe Good Vibrations as "a feel-good movie." But this isn't The Commitments Go Belfast. It's also not 24 Hour Party People (In a War Zone), but that would be a slightly more accurate description.

The climactic scene looks like the end of a feel-good movie, but if you’re paying attention, it actively subverts the feel-good trope. It’s honest, and life doesn’t work like feel-good movies say it does.

The actual feel-good scene happens much earlier.

It's when Hooley goes to check out this punk music at a local club and is filled with the spirit of youthful rebellion. If you ever had a transcendent experience in the midst of a sweaty crowd, bouncing to three-chord music with a steady backbeat, you'll recognize it. If that same evening included heckling a couple of cops hassling kids into leaving a bar, you'll relate to it.

By the concert’s end, Hooley has not only become a musical convert but also decided to start a record label. He signs Rudi, the band depicted onstage whose songs "Cops" and "Big Time" are featured in the scene.

"Cops" is about the so-called Battle of Bedford Street in 1977 when the Clash were forced to cancel a show at Ulster Hall. In a show of unity, disappointed Catholic and Protestant punks took on the Royal Ulster Constabulary in a non-sectarian riot.

That's not shown in the film. The punks are shown instead as heirs to Hooley's "old hippie" strain of pacifism. But in the middle of a civil war, rioting for the right of people divided by a conflict they didn't choose to come together doesn't seem entirely non-pacifistic.

This stands in contrast to the moment when Hooley describes his old pacifist friends joining sectarian paramilitaries and trying to kill each other.

In many respects, punk was a backlash against what was seen as the failure of the "peace and love" approach to effect actual, lasting change. Hooley's take is a little different: "I'm just an old hippy and punk was hippies' revenge, cos you didn't listen to us first time round!"

The timing was spot on. A month after Good Vibrations the record store also became Good Vibrations the label, Stiff Little Fingers self-released their first single "Suspect Device" on cassette. Northern Ireland's punk scene, centered in Belfast, was taking off.

Like Rudi, the bands tended toward a poppier sound than the more abrasive directions London bands were taking punk. And the clothing and lyrics tended to be different, too. In London, the Clash might wear military surplus and counter "peace and love" by singing "Hate and war is the only thing we have today." That was a little close to the reality the Belfast bands were reacting to. Instead, most of them focused on the concerns common to teenagers both inside and outside of war zones.

Stiff Little Fingers was an exception. The first breakout band from Belfast, they signed directly with Rough Trade on the strength of that cassette. Their songs had a harder, rockier sound and addressed the Troubles directly. This attracted criticism from other bands who claimed they were exploiting the conflict for an audience outside Northern Ireland. This would be a notable theme with The Undertones, who were soon to arrive on the scene.

Now they are talking about shows they saw. I'm happy to sit and listen.

My more alternative friend saw Stiff Little Fingers. Several times. I'm jealous.

Both of them saw Rudi. The only song I know is "Big Time," but still, it's a great song.

The Undertones. They both saw The Undertones. OMG.

Around the end of 1979 or the beginning of 1980, a friend with more disposable income and access to the limited flow of alternative music coming into our small city made me a mix tape. I didn't have a decent stereo or even a boombox, just a cheap, portable mono cassette recorder. But when I pressed play and the first song started, it transcended the limitations of the playback system and spoke to me in a way no other music ever had.

You might be reading this and expecting me to say I'd just heard The Undertones' "Teenage Kicks" for the first time, but you'd be wrong. It was "Get Over You," the A-side of their second single. It would still be a while before I heard their legendary first single.

"Teenage Kicks" was on the Good Vibrations label, and the movie makes much of Hooley getting it to influential BBC DJ John Peel. There's some license taken, but there's also some truth to it. At any rate, Peel liked it so much that he played “Teenage Kicks” twice in a row on his show. He also had its first line inscribed on his tombstone.

The Undertones weren't from Belfast. They were from Derry, Northern Ireland's second-largest city. It had a third the population of Belfast, but it was where many of the most notable and tragic events of the Troubles occurred.

If the Belfast punks were notably less fashion-focused than the London punks, The Undertones were practically squares. (One thing Good Vibrations nails is the look of punks in places where, instead of boutiques and salons, people were going to thrift stores and cutting each other's hair.)

Stiff Little Fingers was the first inkling much of the world had that, despite everything, a music scene transcending sectarian boundaries was gaining steam in Northern Ireland. The Undertones confirmed it was something different and very special. Seymour Stein, the head of Sire Records, was listening to that John Peel show and immediately signed the band.

Although punk remains a relevant genre and lifestyle influence around the world, in most places where scenes developed, they had a heyday of a year or two. Then, they splintered into myriad forms of post-punk and local forms of hardcore, which then splintered in turn. But, as shown in this segment from the BBC show Something Else, the Belfast punk scene was still going strong in 1980, after most of the rest of the UK had moved on.

It's never really possible to pin a date to the end of a scene, but 1982 is a potential waypoint. The Good Vibrations label was long gone, and the record store was following suit. The mainstay punk dive, the Harp, became a country and western bar, showing how much of that initial energy had run its course.

The worst days of the Troubles were over, and that might be a coincidence, but this new generation didn't show much interest in keeping the conflict going. Still, the damage was so deep that it took until 1998 to reach an agreement on how to move forward.

We so often think of rebellion and resistance as being about direct confrontation. Certainly, that's been the point of most of the political punk music of the last fifty years. And some bands in Northern Ireland, most notably Stiff Little Fingers, didn't shy away from it.

I do believe that's important. But after listening to my friends who lived it, I take another idea more seriously: In the middle of the Troubles, bands like The Undertones, who did songs about what most would consider normal teenage life, were more radical than they got credit for.

"Teenage Kicks" is not a complex song. The protagonist is horny and yearning for a girl to come over while he has the house to himself. It's just another variation on rock and roll's most-told story, although a little blunter and more honest than the versions that tend to rise up the charts.

What really propels the song, not just musically but in terms of message, is that template passed from the Ramones to the Sex Pistols, the Clash, the Buzzcocks: A simple chord progression, a simple 4/4 beat, an urgency to the vocals. It sounds for all the world like this personal story is so important that it's the reason these guys picked up instruments.

That's what drives the heartbeat of punk. And it's why even in a largely post-rock landscape, basic rock and roll as a music of teen rebellion still hasn't f-f-f-faded away entirely.

It's a relatable song no matter where in the world it's heard. But I have to think that for a lot of kids in Northern Ireland who understood The Undertones were from Derry, there was an extra layer to it they may not have noticed consciously. The lyrics were about the yearning, but the vocal delivery and the music were about anger.

Anger at the bastards putting ideology over humanity. Anger that this most universal of teenage emotions was secondary to worries about a conflict that could disrupt or end their lives at any moment.

Form follows function.

The medium is the message.

What's so funny about peace, love, and understanding?

A stage musical adaptation of the film Good Vibrations premiered in Belfast in 2023. Seventy-Five Revolutions, a biography of Terri Hooley by Stewart Bailie, was published in 2024.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmBrook Ellingwood

The TonearmBrook Ellingwood

The TonearmChaim O’Brien-Blumenthal

The TonearmChaim O’Brien-Blumenthal

Comments