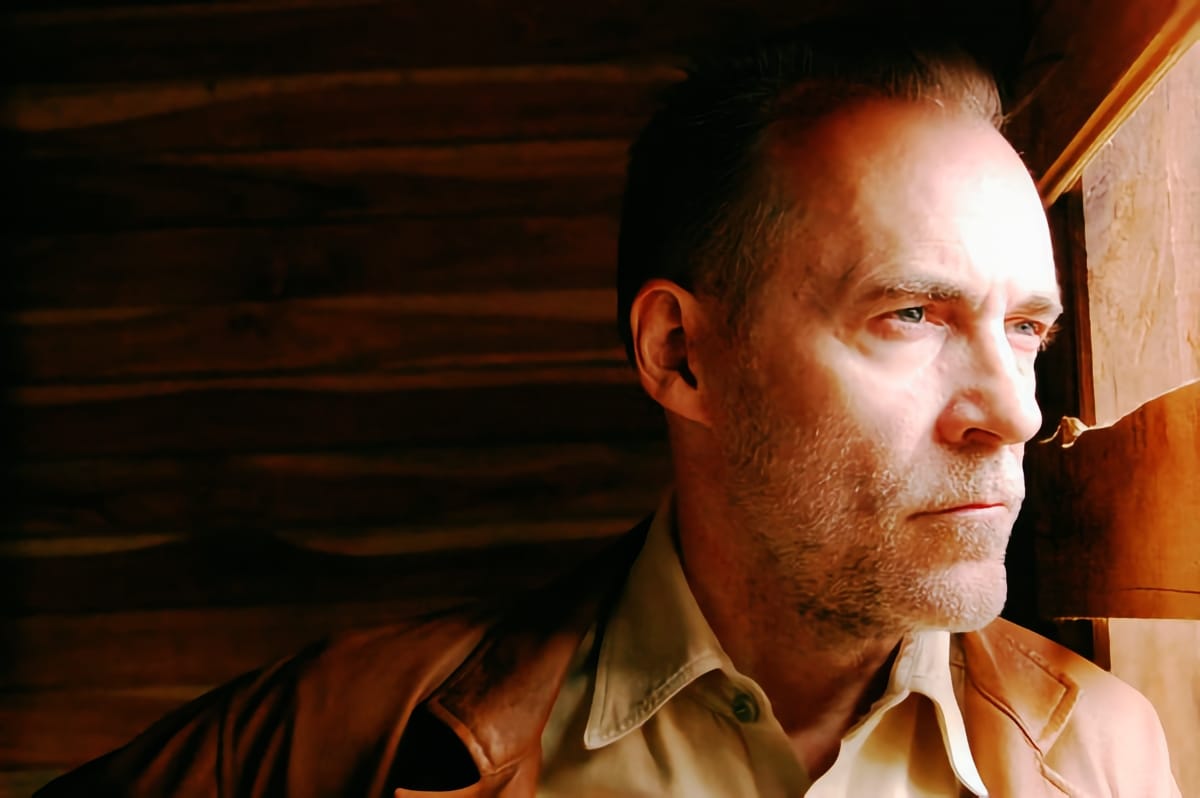

At the heart of New York’s creative downtown explosion in the late 1970s and the following decade sat Arthur Russell, a cellist and composer whose work spanned disco, avant-garde classical, and folk—often simultaneously. Among Russell's closest collaborators was Steven Hall, a Scottish-born musician whose journey from church choirs to The Mudd Club offers a unique window into a pivotal era of musical experimentation.

Hall's musical foundation began in Scotland during the 1960s, where his formal education included orchestral training, church choir singing, and even learning the bagpipes. After emigrating to the United States at fifteen, Hall eventually made his way to New York, where poet Allen Ginsberg recognized his talent and introduced him to Arthur Russell. This meeting sparked a creative partnership that would define much of Hall's musical career—performing as The Sailboats in legendary venues like Max's Kansas City and lending his voice to Russell's disco productions, including "Tell You Today" and "Is It All Over My Face?"

Following Russell's death, Hall joined other musicians from their shared circle to form Arthur's Landing, a group dedicated to performing and preserving Russell's musical legacy. Most recently, under the name Nirosta Steel, Hall continues creating his own “queer love songs” and remixes. His reflections on working with Russell reveal a deep philosophical approach to music-making that embraced Buddhist concepts, spontaneity, and the elusive nature of artistic "completion." In Hall's recounting of their creative process, we glimpse how Russell's perfectionism and perpetual revision created works vibrant and unresolved, existing in multiple versions across linear time.

Steven Hall was host Lawrence Peryer’s guest on the Spotlight On podcast in September 2022. We’re reposting his interview in advance of author Richard King’s appearance on The Tonearm’s forthcoming livestream event (April 22). Richard is the author of Travels Over Feeling: Arthur Russell – A Life. Please join us as we explore the legacy and influence of the late, great Arthur Russell. Register for free to join us.

You can listen to Steven’s entire conversation with Lawrence in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for length, flow, and clarity.

The Center of the World

Lawrence: What was the end of your experience in New York like? What were you doing in the latter part of your time in New York?

Steven: Ever since I grew up in Scotland, my idea was to live in New York. New York was just the place to be. When I moved there, I started making connections—it was the center of the world in terms of style, especially music. It had the best studios, the most interesting clubs where disco music emerged.

I've been lucky to have met or found people who have helped me. I was thinking earlier today about, in terms of Arthur's work, how so much of it was made possible by his partner. I had a partner at that time also, for many years. There's an expression that the best teacher is simply the one who gives you permission. You can see that in a Buddhist context or just in a general context.

So the idea of having a partner who supports you, I think, is a really big part of it. When Arthur and I were working together, we lived about two blocks apart. We were both married—we had partners who supported us and let us do what we wanted all day: to get together and play some music. To be able to have that freedom, I think, is a privilege.

Lawrence: When you read interviews or accounts of people who were close with or worked with Arthur Russell, his impact on people still feels very visceral, all this time later.

Steven: Well, it's ongoing because people who encounter him, particularly those who encounter his voice—I've often heard people say that when you hear him for the first time, they just have this "wow" moment, and it's just like something opens up in their head. One obstacle Arthur’s Landing had as a band was that people were attached to Arthur's voice, so they weren't necessarily interested in hearing our versions of the songs.

I think that's exactly what Arthur was trying to do. I'm not as serious about Buddhism as I was when I was younger, but Arthur was totally serious about Buddhism, trying to break through, trying to get past his ego. And also, he had a very real dialogue with Allen Ginsberg about how to apply these concepts to what we were doing. We weren't political like Allen, but we were trying to be completely free in our music. And that, for us, was like a political act—to have no restrictions on what we were doing.

Most of what we were doing was in the studio, because at that point, people were getting into the idea that you could do anything in the studio, that the studio was like an instrument. The studio was like heaven for us. And for Arthur, the idea of being in heaven was to be given the keys to a studio by one of his friends who was an engineer, and then just left there all night to do whatever he wanted. Just total freedom.

Lawrence: With all of Arthur’s productivity and freedom, is it safe to assume that perfectionism is what kept so little of the work from coming out in his lifetime? He just couldn't free or release it, and was never done with it?

Steven: Well, he had two very distinct sides to his personality. One was being supremely confident. He knew he was talented. He knew he had something. On the other hand, he was scared because he had had experiences playing in a club in the West Village where the owner, who had booked him, told him to get off the stage, that his voice was terrible.

So that's why he worked with singers like me, Ernie Brooks, or Joyce Bowden, who were more comfortable being out in front. He had no idea he would be the singer—that developed later. And also, partly when he got sick, that developed more as a practical aspect because he was just simply doing things at home.

I’ve seen interviews with Billy Joel and John Lennon saying the thing about never liking their voices. But in the case of Arthur, he would not be writing, like, a gay song for a woman to sing, although sometimes women ended up singing those songs. He was just writing whatever he was thinking about. Many of his songs have the quality of a diary of whatever he was doing that day, what he was seeing, or what he wanted to say to his boyfriend when he got home from work. Like, "What did I do today? What did I see today?"

Lawrence: Was he able to communicate outside of music? Was that how he communicated with people, or was it just more practical—him channeling his life through his music?

Steven: He was very charming and one of the funniest people I've ever met, so he was very good at putting people at ease. And because he was working as a producer and coming from being a musician, he was very good at putting other musicians at ease. I find the same thing myself—I work as a producer. Especially to work with singers, to be a singer working with other singers, it really helps.

There was just something about him. You could say it was charm. There are only a few people I've met who have that quality—people were sort of drawn to him. And when he started to play music, people just got it. They just understood right away that he was doing something really interesting.

The Party's Already Happening

Lawrence: How do you view, as a creative person, the performance versus the studio? Do you have a preference, or are they different sides of the same coin?

Steven: Because of the way I worked with Arthur, we always try to have a party in the studio and the same thing on stage. In the studio, I try to have everything be as live as possible, as Arthur did. And when we perform, we try to have the band start playing even before people get in. It's like the party’s already happening when they get there. And I was fortunate; Arthur's Landing had a few big concerts we made into dance events. My favorite thing, especially, was the few times we got to play outdoors. That's special.

The studio is more of a slog, like hard work, because I don't have the technical skills that some of my friends have, who are mixing all day long. So often, what I'm looking for is elusive and mysterious, because mixing’s not a natural talent for me. Sometimes I can find it. So I have a great respect for people who can mix well.

The big question I've been dealing with comes from listening to the stuff I recorded when I was younger. So I’m battling with how to record things differently—to sing without irony, which is a real challenge for a New Yorker. Some great singers like George Jones, Arthur's favorite country singer, have that quality and sing without irony. So that's one thing I'm working on.

The other thing is adding vibrato, because Arthur's number one rule, and the only time he would really get angry, was that he never wanted you to sing with any vibrato. The idea was that you should sing more like a trumpet player. He loved Chet Baker because Baker sang like a trumpet player. So he would play Chet Baker singing and say, "I want you to sing like that, but no vibrato." And he would get furious if any of us—Joyce or I—would add any. So, one thing I've been trying to do in the last month is just let myself sing with vibrato.

Lawrence: I can recall specific instances of reading references to Arthur or his voice, and it would always say "and his vibrato-less voice" or "completely free of vibrato." It's like it's such a defining characteristic.

Steven: And also the idea of hitting the note just pure, as opposed to jazz singers, who usually come under the note and then slide up to it. Many of the singers we admired were doing that, but he was just completely pure. And at that time, when I first started working with him, he was also playing drones on the keyboard. He would hold down one or two keys on the keyboard with a pencil and a book, and just play along with the drones. So the idea was that the voice would be another drone.

Lawrence: Being in New York then, how did you come up against hip-hop’s early years? Did hip-hop bleed into your world?

Steven: Not so much. I mean, Arthur was working with Sleeping Bag Records, and they started to get into doing hip-hop music pretty early, I think. But it wasn't part of our world so much. I came up with songwriting and songs from the text because I was studying writing, doing music for fun, and studying poetry at Columbia. But I liked the production, sound, and beats, but I didn’t know much about it.

Lawrence: Yeah. I guess that surprises me to an extent because there’s a sense of everybody sort of being cross-pollinated, whether it was the no wave downtown stuff and how that butted into dance music, which also had the hip-hop adjacent community. It occurs to me just how few people there really were in these early scenes. Like, it's New York, it's massive, but it seemed like everybody knew each other.

Steven: I think because there were certain places like The Kitchen where people were open to having different styles. Arthur was programming there for a while, and he brought different styles. When you think of it in terms of the sexual revolution followed by a kind of music revolution afterwards, there’s the idea of things opening up and people being more open-minded.

The thing about Arthur, me, and some of the musicians I know was said about Bob Dylan by the famous French pop singer who was like the Elvis of France...

Lawrence: Oh, Johnny Hallyday.

Steven: Yeah, Johnny Hallyday was asked, "What was your impression of Bob Dylan? What is Bob Dylan like? What was Bob Dylan listening to?" And Johnny Hallyday said, "The only thing Bob Dylan ever listened to was Bob Dylan." So that's really like a huge weight off my shoulders because Arthur and I would just spend hours and hours listening to different mixes of his or my own stuff, and basically that's still what I do. I mean, I love to encounter songs by other singers, and I love to do covers.

Lawrence: What is your music? And I don't mean your music as a creator. What music do you hold dear, or that most impacted you before you started making music?

Steven: Well, I grew up in Scotland, so I had a great music education in school, where they had a full orchestra, and in church. Not only a traditional church in the church choir, but I was also involved in youth groups playing folk music. So that's where I got into playing acoustic guitar, singing harmonies, and trying harmonies that were kind of way out, which people were open to in those groups, like playing on a beach on the west coast of Scotland. And then at the same time, I played the French horn in the school orchestra, so I was studying classical music, and then I played the bagpipe as well. So I have a background in all of those things.

And then I came to America, which I always wanted to do. My mother remarried, and we came here, and then it was like an explosion of listening to music. And then I started playing the guitar seriously. But also the dulcimer because of Joni Mitchell—huge influence in terms of the way I approach playing the guitar.

When I started working with Arthur, he went through a whole bunch of genres during the time we were working together. At that point, he wanted to play country music. When we met, he liked my guitar playing because it was simple and flat. I had this sense of patience. And then the other thing is my guitar has a wide fingerboard. My hands are big. I'm made to be a piano player. I'm okay on the piano because I can play an octave, but this isn’t good for playing guitar.

So I can't play an A barre chord. But I could play an open A. So when Arthur and I were playing acoustic guitar together, I couldn’t play the same A if he was playing an A, so I would have to play a variation. So we ended up playing variations and sort of melding together where we'd be playing the same chord, but I'd be playing an open version. It would end up melding together nicely, and then we’d harmonize.

Later, he got into heavy metal on the cello. He was studying Guitar magazine and trying to find out which pedals the heavy metal players were using, and then getting those pedals, like the Big Muff. I was studying John Martyn who was also getting into these heavy pedal sounds.

Arthur went through disco and then into rock through the Necessaries and the Flying Hearts. What he ultimately wanted was to be like Philip Glass through classical. So he went into doing the opera with Robert Wilson, but everything fell apart. After that, he went into seclusion because that experience with Robert Wilson was so crushing. In one way, it was his masterpiece, but it was only performed once in a workshop setting. Robert Wilson wouldn't perform it again because they had such a bad experience working together. It was simply two big geniuses, both controlling. Arthur was confident at that point, and Robert was a superstar. It was just like two magnets coming together and repelling each other. But they produced a great masterpiece. The work is amazing, but it never got its full performance.

Lawrence: What's the issue? What is there that there's so much room to have discord over in artistic collaboration? Is it everything?

Steven: I think a lot of it has to do with what came up in Arthur's Landing. We all loved Arthur's music and loved Arthur. One of the things that came up was the production, how something would sound. That became a big thing because it had to do with our feelings. I was working as a producer for years. Peter Zummo, the trombone player, had a home studio he'd been working in for years. Ernie Brooks, the bassist, had his home studio. And then Joyce, the other singer, also had a studio in her home. So everyone had their particular ideas about how things might sound.

And then also, we thought we would suddenly get famous. We probably would have achieved a certain degree of fame if we hadn’t been foolish. I've talked about this before—a certain desperation. We were all older, and this was kind of our last chance to "make it." We also got a taste of something that could be big if we could keep cool, but we couldn't keep cool. With older musicians, everyone's kind of set in their ways.

So when you're in a group or working with someone you've known for a long time, it's like a relationship or a love affair. That aspect of it becomes very, very tricky. So, in other words, to answer your question, the short answer would be: details. It comes down to very, very specific details.

Like in Arthur's Landing, one of our huge fights was over one of Arthur's songs. Joyce sometimes liked to rap or talk at the beginning of the song. Once the groove got going, she would just say something or talk; sometimes it was charming, and sometimes it didn't work. She once said something about an alarm clock, which we thought was just off-the-wall and interesting. So we were going to leave it in. Then I think Brennan Green added an alarm clock ringing to the track, and Peter just went completely insane. He said, "This is too literal. Why are you making it so specific? It's already very explicit." And for weeks, we fought about that. I was in the middle because I was kind of both ways, but those two were the two main producers. That detail became everything that they thought was important.

Lawrence: What resonates for me about that, as somebody who has played a bit with other people and been in studio situations, is that any of those individual conflicts—you can say they don't matter, but they do. Like, the placement of the alarm clock does matter. And I can understand how it becomes a proxy for all the other battles about creativity and interpretation.

Steven: Well, here's the bittersweet part. Peter was right, but he doesn’t talk to me now. So I can't tell him. Maybe he'll read this. (Laughter) I put the music first, and sometimes I think that was a mistake in terms of relationships. I could have put relationships first.

There's a comment made about John Martyn. He was married to a singer, and they were both folk singers. When they divorced, his wife said it was inevitable because "you can't have a relationship with a singer. All their emotions go into their songs and the singing, and there’s nothing left." So that's an interesting way of looking at it.

Don't Be Afraid of Pretty

Lawrence: I wanted to ask you about Allen Ginsberg and his interaction with and influence on you as a songwriter and lyricist. Is your self-conception that you are a poet?

Steven: The two things were separate before because I was studying poetry very seriously. I was part of the poetry scene—St. Mark's as well as the Columbia scene. So uptown and downtown, I was trying to be a bridge between both. And I was also playing in pop bands in school, but that was for fun.

Allen introduced me to Arthur, and Arthur was the first to take me seriously. I was pretty unsure about my songwriting capabilities. Also, compared to him, it was like showing Duke Ellington your exercises or something. But it's very poignant because the only two songs we wrote together—he wrote very few songs with other people—were those that he actually finished.

Because with "Lost In Thought," I had this pretty beginning, just repeating "Lost in thought, lost in thought, lost in thought…" And I said, "I'm not going to finish this. It's too pretty." He said, "Don't be afraid of writing something pretty. Maybe you're good at that." So he wrote the second part, which is complicated, and added the story—"There's something that I want to say, even if I talk to you, I still can't come home." So he wrote the bridge, which goes back to "Lost in Thought." And then the other song we wrote together, he wrote the chorus, which he wrote in a higher register for my higher voice. So that's interesting to think about.

Lawrence: Can you share any anecdotes about Ginsberg?

Steven: Well, just maybe a couple of sayings. He would say, "The only good thing about money is you can throw it at your problems until they go away." So I always think about that in terms of how to approach money.

Arthur wanted to become famous and make money. He got a taste of that when he was alive because a couple of his disco songs suddenly made a lot of money. He was just given a whole bunch of cash all of a sudden. So he got a taste of that, but he said his main idea of collaborating with his friends was to create a fountain of money that would rain down on his friends. So I like that idea too. Those are a couple of good quotes.

Also, the thing about Allen was that Arthur helped him learn the basics of doing music, but Allen's whole thing was that he had a difficult childhood, and he said, "This is my second childhood. I just want to be a rock star and just be silly and sing these crazy songs, and people will let me get away with it." So Arthur and I helped him to do that. I like this idea of the second childhood—that's what I'm hoping for.

Follow Steven Hall (under his latest project name Nirosta Steel) on Instagram and check out his label Buddhist Army on Bandcamp.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments