Greg Davis began his journey in the angular rhythms of hip-hop and the spontaneous expressions of free jazz but soon found himself drawn toward the unmoored possibilities of electronic composition. His path from DePaul University's classical and jazz guitar program to creating mathematically generated compositions and billowing ambient soundscapes mirrors the broader transformations in experimental music over the past three decades—from physical instruments to digital manipulations, from traditional forms to randomized circuitry.

Following a fifteen-year gestation period, Davis returned to his new-age-inspired Full Spectrum series with 3/7, two side-length compositions issued on cassette. These pieces began their lives in different moments—Part 3 emerged from sessions in 2009, and Part 7 was originally crafted for a 2012 performance at France's IAC. These sounds have grown through years of careful tending in Davis's Burlington studio, where he splits his time between aural experiments and operating Autumn Records, his vinyl emporium in nearby Winooski.

The music Davis releases under the Full Spectrum series flows like drifting deliberation—clusters of harmonious tones appear and disperse, each new pattern suggesting inner flux while remaining grounded in Davis's intricate understanding of composition. His work has always juggled the visceral and the cerebral, drawing equally from Buddhist philosophy and the retro-futuristic dreams of early electronic pioneers. Full Spectrum continues that tradition of gentle mind/body dissolution, creating environments where listeners can disappear in thoughtful patterns of carefully orchestrated sound.

The ever-affable Greg Davis and I spoke soon after the release of Full Spectrum 3/7. I interviewed Greg previously about his 2020 album New Primes, released on the greyfade imprint, and Full Spectrum, an entirely different compositional beast, inspired me to continue our conversation. We chatted about the process behind the Full Spectrum series, why there’s such a long gap between releases, and how Greg is happy to have the music categorized as new-age. Greg also treated us to a list of foundational and obscure new-age music releases—seven personal picks rescued from the dusty back bins of used record shops.

A Bin of Stuff in the Back

Michael Donaldson: Let's start with the Full Spectrum series. Can you explain the background?

Greg Davis: The Full Spectrum series began during my touring years in the early 2000s. I was doing electronic music and playing shows everywhere, and whenever I'd visit a new city, I'd seek out record stores. During that time, I started collecting new-age records. The new-age section was always this neglected corner of the store—just a little bin of stuff in the back.

I started buying records from these bins, which were always really cheap. My goal was to find what I considered good new-age music. There's a lot of corny stuff out there, but I knew there had to be some good material—ambient, drone, cosmic music—that had a kinship with what I was making and what interested me.

Michael: When looking for these records, was there a certain era you focused on?

Greg: Primarily stuff from the '70s and '80s, either on vinyl or cassettes. I spent a lot of time buying things and taking chances. There were plenty of duds, but I found many great records too.

In 2007, during the height of music-sharing blogs, I started a blog called Crystal Vibrations. I shared all my favorite new-age discoveries, ripping vinyl or cassettes and posting them. The blog is still there, though I haven't touched it in years. The download links probably don't work anymore.

Around 2008, I started making the first Full Spectrum pieces as homage to this music I was deeply exploring. The first Full Spectrum cassette came out in 2009 on Digitalis, which Brad Rose has been running for years. It contained parts one and two. Full Spectrum part three, on the new cassette, was partially created during that time but sat around for years. About five years ago, I dug up that material and kept reworking it until it became the piece on the new tape.

Michael: So you weren't constantly working on it over that span?

Greg: No, I've jumped in and out of the series over the years. The pieces are all made with a specific process and have a certain vibe and sound. I might jump into that mode whenever I’m in the mood to work on that stuff. I worked on pieces around 2009-2010, then a bit more in 2014, and didn't touch them again until around 2020. Finally, I got four pieces over the finish line within the last year. They were released as two companion cassettes about a month apart—Full Spectrum three and seven on one, and five and six on another released by Blue Tapes in the UK.

Michael: Were there specific triggers that would send you back to working on it?

Greg: This music is almost like a refuge for me—very peaceful, lush, beautiful ambient music. I would return to it if I ever needed to escape into that world and immerse myself in those sounds. These pieces can be worked on extensively—processing, mixing, and layering. I make all kinds of electronic music, some very abstract and experimental, but I tend to have multiple threads going simultaneously. That gives me the freedom to work on whatever feels right at the moment.

Michael: When you say working on this music is more peaceful, does it take less thought than your more processed pieces?

Greg: Right, it's less conceptual. We talked about New Primes last time—that's a very conceptual piece where every detail is mapped out in a system that runs itself. This music is more intuitive, focusing on how it sounds and feels. The processing, mixing, and structural decisions are based on feeling out the flow and form.

All these pieces are intentionally long, around 15 to 20 minutes each. With drone and ambient music especially, I like to give listeners a chance to immerse themselves. The length also allows things to change subtly over time—you're immersed in this sound world, and by the end, you've taken a journey even though you're still in a similar space.

Michael: The ebbs and flows within the modulations are pronounced within the overall composition. To me, it has the effect of condensing time in the pieces.

Greg: Yes, these pieces have a more traditional musical structure than some of my other music. Sometimes, I like totally flat, static pieces that exist in one zone without dynamics, but these almost feel like orchestral pieces with tension and release, buildups, and louder and quieter parts—hallmarks of traditional arrangement and orchestration. Having those kinds of movements in a longer piece makes time feel different because there's activity happening.

Cosmic Hippie Jams

Michael: Going back to searching through bins for new-age stuff, do you differentiate between new-age and ambient?

Greg: There's a fine line. new-age music started in the mid-seventies, growing partly out of the California post-hippie scene. Some of the first proper new-age records were Stephen Halpern's Spectrum Suite around 1975 and Iasos's early work. But it wasn't called new-age back then—they hadn't codified the term. Those records almost sound more ambient, with a cosmic hippie jam feel.

It was a mesh of that era, plus spirituality coming in. In the '80s, it got commercialized—that's when you get Windham Hill and compilations for yoga and meditation. But in that beginning era, many threads were coming together: ambient music, minimalism, modern classical, and kosmische music from Germany, especially Berlin School synthesizer music. These elements were all in the air. Then Brian Eno started his Ambient series with Music for Airports in the early '80s, which really popularized the term "ambient music."

Michael: I worked at Camelot Music in Alexandria, Louisiana, around '87-'88. We couldn't keep Windham Hill in stock. This was a mall record store in central Louisiana—it gives you an idea of how huge that movement was at the time.

Greg: It's crazy how popular it got. I've listened to most of the Windham Hill catalog, and honestly, there's not much I particularly enjoyed. There are almost two versions of new-age music: the instrumental acoustic version with piano, guitar, and harp, and then the more electronic version using synthesizers. I always gravitated toward the electronic stuff. There are a few good titles in the Windham Hill catalog, but generally, it wasn't for me.

A Big Cloud of Harmonic Sound

Michael: Can you talk about the technique behind the Full Spectrum compositions?

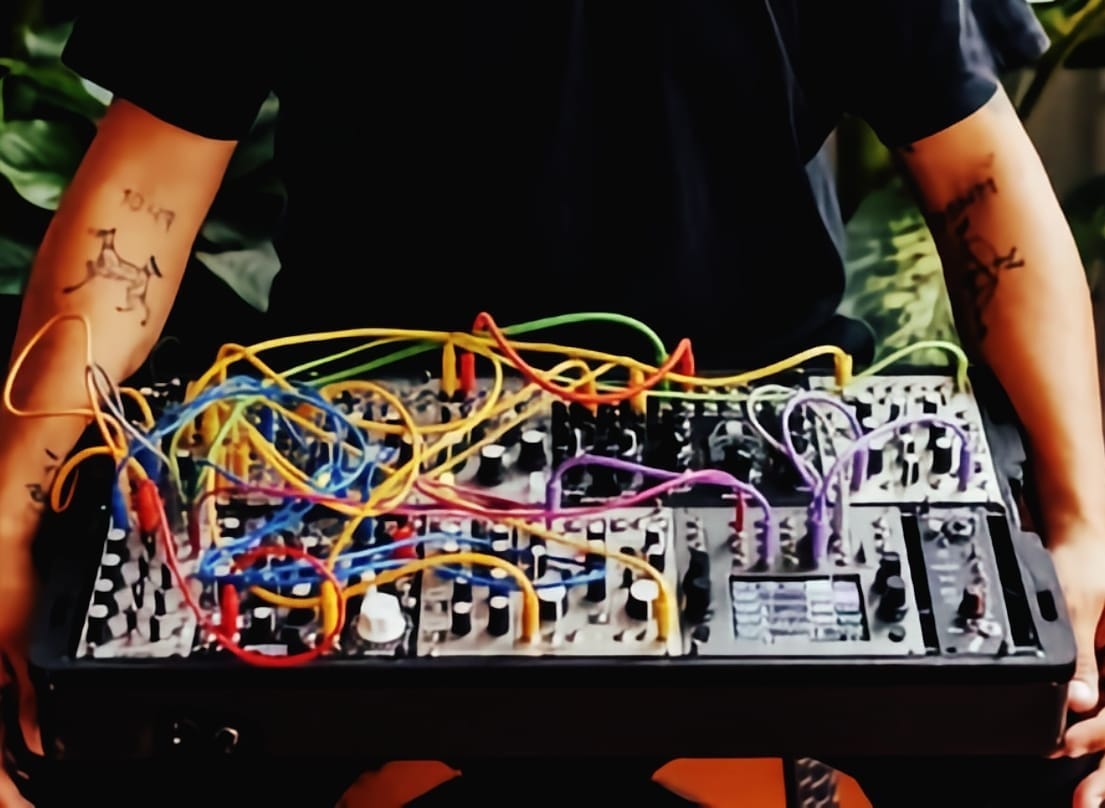

Greg: The first pieces started as an experiment. I made these noodley, improvisational keyboard pieces using different synths and a Fender Rhodes electric piano, playing around with tones that reminded me of Stephen Halpern and others. One time in my studio, I recorded a short two-minute piece and decided to run it through a delay pedal with an 8 or 12-second delay. I put it on a loop and recorded it with the feedback set to 100%, creating a continuous sound-on-sound recording. I let it run for 24 hours.

When I came back and listened, the process had filled out the whole space, blurring and smearing everything into a big cloud of harmonic sound—hence "full spectrum," filling the whole spectrum of sonic space. I recorded the output, brought it to my computer, and manipulated and processed it. That's the seed of every Full Spectrum piece: running material through this delay system, recording the output, and building from there through processing and layering.

Michael: I'm really into discovering compositions through randomness, so this appeals to me because you don't know what you will end up with when you start. Have you had attempts where you returned hours later, and the result didn't work?

Greg: Exactly—it doesn't always sound good. It depends largely on what material you're feeding into it. What works best is something in one key or chord. If you have lots of chord changes, it becomes a dissonant mess after repeated delays. I've had pieces I couldn't use, but that's the beauty of it. You let it run, come back, and think it's amazing or awful.

I've made what I call "seed sounds" for Full Spectrum one through six, and I have seeds ready for eight through eleven. At some point, I'll start working on those too.

Michael: It's interesting that there was a 15-year wait between releases, and now the project seems to be moving forward.

Greg: Well, that was due to various life changes. I did music full-time from 2000 to 2010, but then I had a kid and stopped touring. Then I went through a divorce, and I opened a record store eight years ago. My music-making slowed considerably from 2010 to 2015—I wasn't making much at all. But I’ve found more time and space for it in the last five or six years.

Michael: It's almost like a statement, whether intentional or not, to wait until the time is right rather than giving in to outside pressure to keep producing.

Greg: At first, it was really hard. I'm always compelled to make music and have many ideas, so not having time and space was frustrating. But eventually, I made peace with working at this pace. Nowadays, there's so much pressure to produce ‘content’ constantly. I saw something recently that said more music was released in a week in 2024 than in all of 1989—that's crazy.

I've learned just to make stuff, and when it's done, it's done. If five people hear it and it disappears after two weeks, that's fine with me. I still want to do what I want and put it out there, even though everything disappears so quickly now.

Michael: That's one of the inspirations behind The Tonearm. A lot of music we liked was getting lost, and when researching show notes for the Spotlight On podcast, I'd look for articles or interviews with these interesting jazz musicians and find nothing. No outlets were writing about these people.

Greg: That's great—more people should be doing that. Sometimes, it's frustrating seeing the same people get written about repeatedly, even in my smaller niche of experimental electronic music. I self-released these recent recordings and sent promo emails with download links to hundreds of writers, hearing back from maybe three people.

It was also interesting to release ambient records now, given how much ambient music is out there. Ambient music has become ubiquitous in the experimental electronic music world. But I don’t care—I’ve got a couple of records I’m happy with, and this shows that this has been a thread in my music all along.

Michael: I think being upfront about the new-age influence shows a sense of history that others lack.

Greg: What's interesting is that my Crystal Vibrations blog became quite important. Many musicians have told me it turned them on to this music and made them feel comfortable exploring it. Matthew David from Leaving Records in LA was obsessed with the blog. Whether you call it new-age, ambient drone, or cosmic music, I just love how some of these things sound. There was definitely a resurgence of "cool" new-age music for a while, which I think evolved into the ambient music movement we're seeing now.

After our conversation, I kept thinking about Greg Davis trolling through bins of fluffy piano music, hoping to find the rare new-age gem. I emailed Greg to ask if he’d reveal some of the highlights of his music-digging excursions. Greg enthusiastically replied with seven little-known examples of strange excellence from the much-maligned new-age genre. Happy hunting!

peter davison - selamat siang - music on the way (1980)

"lovely flute / synth / saxophone / harp / cello / guitar record. dreamy floaty episodic soundscapes. synths emulating birds & ocean waves. deep early '80s santa monica vibes here."

michael vetter - tambura meditations (1983)

"heavy heavy solo tambura trip, if you didnt think that tambura could be played as a solo instrument, here is proof otherwise. vetter coaxes an array of spectral overtones & harmonics from the tambura. deeply ZONED!"

swami kriya ramananda - hymn to a new age (1981)

"super deep meditative drone float. mostly warm syntheszier drone with gong on track 1 & bass flute on a couple of tracks. swami ramananda (a.k.a. edward christmas) is a western born kriya yoga mystic & ordained priest through the temple of kriya yoga of chicago. tone poem, sonic bath, musical journey"

j.d. emmanuel - rain forest music (1981)

"bring the beauty of the rain forest into your mind"

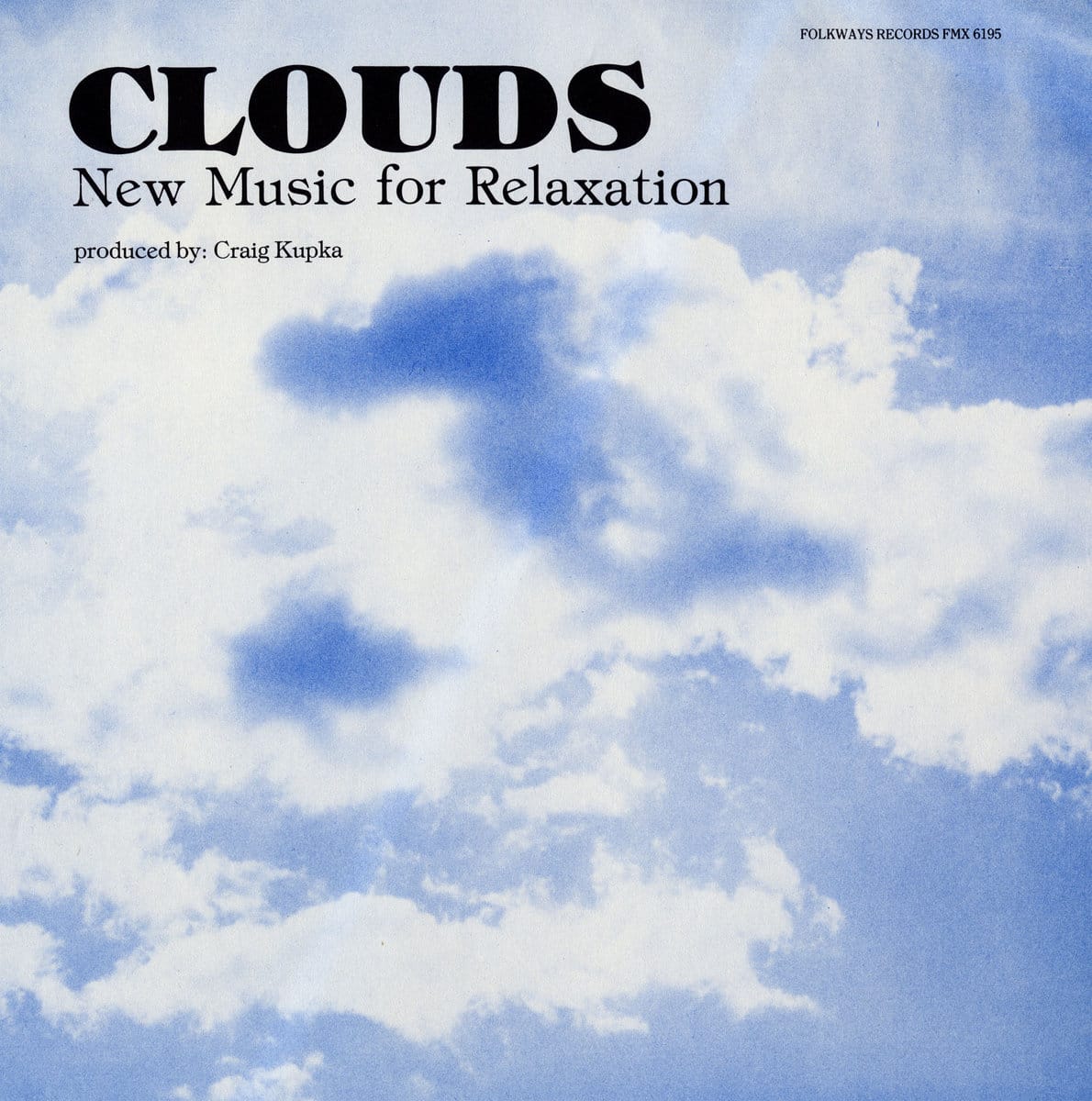

craig kupka - clouds - new music for relaxation (1981)

"in the early 80s, even the esteemed folkways records dipped their toes into the crystal clear new age waters....CLOUDS is a mellow static spaced out record he and his buddies made for the label. tinkly, light & noodly halpern-esque tones make up 2 side-long pieces for zoning out. vibes, celeste, electric piano, guitars, synths, percussion."

don slepian - sea of bliss (1980)

"don's first album of blissful waves of sound. 2 long relaxing meditative pieces perfect for a drizzly summer day."

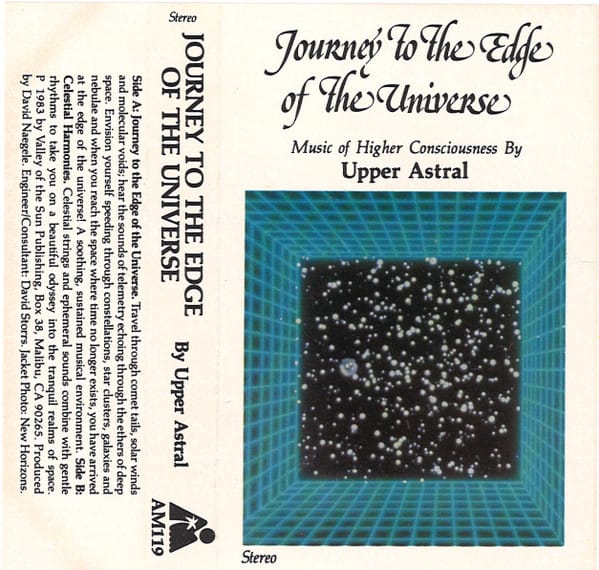

upper astral - journey to the edge of the universe (1983)

"i dont know anything about this 'band' (maybe its bob slap?) except that its some of the best new age cosmic synth music ive ever heard. translucent synth strings, spacy twinkles & rubbery basslines. part of the dick sutphen 'valley of the sun' new age empire. pure gold!"

Purchase Greg Davis's Full Spectrum 3/7 on cassette or digital download from Bandcamp. Visit Greg Davis at gregdavismusic.com and follow him on Bluesky and Instagram.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments