During the eerie stillness of 2020, as Manhattan's crowded streets emptied and practice rooms fell silent, flutist Jamie Baum found unexpected resonance in the daily poems appearing on Bill Moyers's A Poet a Day website. These verses sparked a creative transformation that would reshape her ensemble, The Jamie Baum Septet+, into something entirely new.

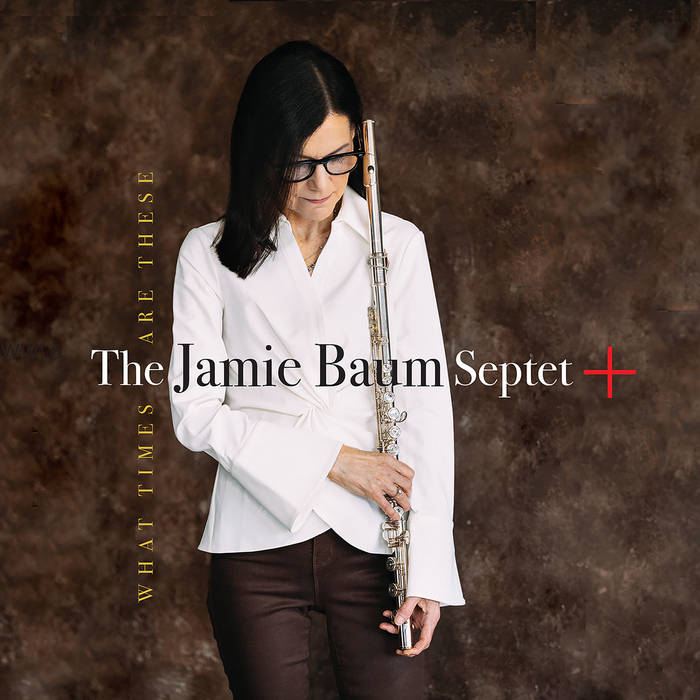

Over twenty-five years ago, Jamie formed the septet that would become her primary vehicle for compositional exploration. Through this ensemble, she has steadily expanded the possibilities of her instrument while crafting intricate arrangements that draw from classical chamber music, South Asian traditions, and contemporary jazz. The flute, often relegated to melodic decoration in jazz contexts, becomes something else entirely in her hands—an instrument capable of profound dialogue with ancient traditions and modern innovations. Her latest album, What Times Are These, marks a continuation of this journey and a bold step into new territory.

Jamie’s encounters with the poetry on Bill Moyers’s site led her to compose pieces that pair her sophisticated musical language with verses from Adrienne Rich, Tracy K. Smith, Marge Piercy, and others. The resulting work brings together an expanded version of her septet—featuring longtime collaborators like trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson and saxophonist Sam Sadigursky—with vocalists including Sara Serpa, Theo Bleckmann, and hip-hop artist Kokayi.

What Times Are These also responds to profound personal and societal challenges. Baum's setting of Naomi Shihab Nye's "My Grandmother in the Stars" resonates with her own experience of caring for her mother during the pandemic, while other pieces engage with broader themes of isolation, connection, and resilience. Throughout the album, Baum's arrangements create spaces where poetry and improvisation interact, supported by the septet's versatile instrumentation and her continued exploration of cross-cultural musical dialogue. The result transcends mere musical arrangement, becoming a kind of sonic correspondence between past and present and the ineffable language of jazz.

Jamie Baum recently appeared on the Spotlight On podcast for an in-depth conversation with Lawrence Peryer about the ins and outs of What Times Are These. The two also touched on the evolution of Septet+, the enduring influence of Bill Moyers, Jamie’s creative process behind setting poetry to music, and the political underpinnings of the project. Listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On player. The following transcript has been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

The Right Words in the Right Order

Lawrence Peryer: Maybe we could start at the beginning of the current Septet+ project. What sparked the concept for the album? What led you to explore the integration of poetry, specifically these female poets, with this project?

Jamie Baum: Until now, I hadn't done much work with voice, except for a couple of things here and there. On my album before the recent one, I had Amir El Saffar sing wordlessly on "Song Without Words," but that was about it.

I was on tour in March 2020, supposed to be for the month, when COVID hit and everything shut down. The last gig before the tour stopped was at Keystone Corner around March 13th. There were only two tables of people, and the next day, everything had to close. I returned to New York.

I live at Manhattan Plaza, an artists' housing in Midtown Manhattan. By New York standards, it's not that small, but anywhere else it would be—a one-bedroom with my husband. We've made it work because one of us is usually out doing a gig, rehearsing, or on tour. That leaves time for the other person to practice or do their thing. Manhattan Plaza has practice rooms, and I had a studio, so it wasn't a problem. But when COVID hit, everything closed—the practice rooms, my rehearsal studio, and teaching moved online at Manhattan School of Music, and all gigs, festivals, and tours disappeared.

Being home, I thought about what I could do. I love to perform and compose, so I decided to write. I had released my last Septet+ recording about a year before so I could start another project, though I wasn't sure what direction to take.

During this time, I discovered a website called A Poet a Day, created by Bill Moyers. Every day, he would post a poem, including a video of the poet reading it and any interviews he had done with them. His introduction stated, "We're here to give you solace in these frightening times and hope that the right words in the right order will give you comfort."

I'd never really been a poetry person until I visited MacDowell, the artist colony in New Hampshire. I heard some Pulitzer Prize-winning poets read their work there, and it clicked. Hearing them read with intent, phrasing, and musicality made me understand poetry in a way I hadn't before when just reading it on the page.

As I explored Moyers's website, I started looking for poems that spoke to me—ones I could relate to or that had meaning, but also ones I could envision setting to music with a particular groove or sound concept. I noticed I was primarily choosing women poets and decided to follow that direction. I've always been somewhat political, and we've been going through some crazy times. Many of the things communicated in these poems resonated with my feelings about current events.

Each poem held a different meaning for me. Adrienne Rich's "What Kinds of Times Are These?" was based on a Bertolt Brecht poem written during the Nazi invasion, addressing the dangers of free expression. Unfortunately, themes about book banning and controlling information remain relevant today.

Naomi Shihab Nye's "My Grandmother and the Stars" connected with me on multiple levels. During this period, I was helping care for my mother in Connecticut, who had dementia and passed away last February. I couldn't see her for about a year due to COVID restrictions until we were both vaccinated. Then, I was traveling there almost weekly to help with her care. The poem provided a way to process those emotions.

I corresponded with Naomi through email about the piece. She wrote it about her grandmother in Palestine, as that's her heritage, though she lives in San Antonio. The opening lines resonated deeply: "It is possible we will not meet again on earth. To think this fills my throat with dust," and then "There is only the sky tying the universe together." There's something particularly moving about how I, being Jewish, connected with her Palestinian narrative through our shared experience of loss and family bonds.

Lawrence: That's very humanizing, right? It makes you realize that regardless of where you're from, we have these shared experiences with our family and parents through the generations. None of us are immune to those sufferings.

Jamie: Absolutely. When I saw Lucille Clifton's piece “sorrow song," the phrasing reminded me of rap, which led me to work with Kokayi. Each piece revealed its musical direction as I worked with it.

Later in the summer, someone asked if I'd sent the recording to Bill Moyers. I hadn't considered it, but I contacted him through his website. Two hours later, I received a brief email with his address on Central Park South. Three days after sending him the CD, he emailed me saying he loved it. He wrote, "My only regret is that I'm no longer doing interviews, or I'd schedule you for one." He even provided a quote for the CD, calling it "a masterpiece of sound and spirit."

Jazz Channeling

Lawrence: Could you articulate how something went from you consuming a piece of poetry, connecting with it, and translating it into music? Do you have a meditative process? Do you just channel it?

Jamie: Sometimes I feel like it's channeling because I think, "Did I write that?" Despite my formal education in jazz composition, I'm a very intuitive writer. Many composers map things out with specific chord changes, but I usually just sit at the piano and noodle until I find something.

I work better with concepts, so I like albums—I can see an arc or direction. I use Digital Performer, a sequencing program that helps me hear my ideas. While I play enough piano to work out ideas, I don't play well enough to execute everything in time with multiple voices. The program allows me to hear things back in real-time, which is invaluable.

The first ideas are usually inspirational, but then comes the challenge of development. That's where skill and patience come in: getting out of your own way and seeing what the piece wants to be rather than forcing it. I don't believe in writer's block—it's more about the questions you put on yourself. If you say, "I've got to write the best thing I ever wrote," you'll get stuck. I approach it as an exercise, knowing I can always revise or start over.

When I was less experienced, I might have tried to force an idea into a specific tempo or style. I’ve learned to step back and allow the music to reveal itself. Sometimes, I'll play something back fifty times until I hear what needs to happen next or sing it while showering or walking. Some pieces come quickly; others, like "An Old Story," went through fifteen versions before recording.

The COVID lockdown provided a silver lining: uninterrupted time to develop ideas organically and return to them daily, which is unusual for working musicians who typically juggle teaching, gigs, and touring. I also set small challenges for myself. With What Times Are These, I wanted to explore singer-songwriter elements, incorporating intros, refrains, and choruses inspired by artists like James Taylor, Carole King, Stevie Wonder, and the Beatles.

I also experimented with musical conventions from film scoring, where certain techniques elicit specific emotional responses. In "My Grandmother and the Stars," I deliberately matched the melodic movement to the emotional content of the words—rising hopefully on "It is possible" and falling on the sadder phrase “We will not meet again on earth."

My background in classical music, particularly studying Bach and Stravinsky, heavily influenced my approach to composition. In my early years in New York, I was doing classical gigs with string players from Juilliard, playing a lot of chamber music. Bach's counterpoint, where independent lines diverge and converge, fascinated me. With Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring, the complex rhythms and ostinatos caught my attention.

This influenced how I approached writing for the flute. In the nineties, the flute was often seen as a miscellaneous instrument, typically playing melody lines while the rhythm section had all the fun playing together. I wanted to legitimize the flute's role and find ways to integrate it more fully into the ensemble texture.

My travels as a jazz ambassador for the State Department, particularly in South Asia—India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Maldives, and Nepal—introduced me to different musical traditions. The music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan particularly influenced me. His artistry reminded me of Pavarotti or Coltrane—there was something transcendent about it. Indian music's lack of harmony provided a blank canvas, while its intricate scales and embellishments informed my approach to improvisation.

At my core, jazz attracted me to artists like Miles Davis and Coltrane, who were always moving forward. I'm not putting myself on their level, but that spirit of constant exploration resonates with me. I try to challenge myself with each project, working with things that excite me and hoping that excitement translates to the audience.

An Arbitrary Choice

Lawrence: There's something in your story that strikes me—when you were coming up, the flute was sort of differently regarded, if it was thought of at all, especially in the context of jazz and creative music. It strikes me that you committed to that instrument. Who were you looking to? Did you have flutists that were inspirational to you, or were you charting the unknown?

Jamie: It's interesting—I look at amazing flute players like Nicole Mitchell, who were obviously completely enamored with the instrument. I don't know if I had that same passion—it was more of a vehicle for me.

I started playing piano when I was about three because my mom had played piano and trombone. I wasn't particularly serious—I never thought of being a musician. I had other interests, but I liked jazz, and a guy who lived near me taught jazz piano. I took lessons with him for about a year when I was maybe twelve or thirteen. But he was a bad alcoholic, and I always had my lesson at 9 a.m. on Monday when he wasn't in a very good mood. That didn't go very well, so I quit piano.

Then I took up the flute, though the story behind that choice is amusing. My parents had this beach house for the summer, and there were these two cute guys next door who would always sit out and play guitar. So I got my parents to get me a flute so I could meet them. (laughter)

What kept me interested in the flute was its versatility—it allowed me to play many different kinds of music. At the time, I was toying a little bit with the saxophone, but my parents weren’t particularly pushing me toward it because it wasn't really considered a "girl's instrument."

The flute offered unique advantages. I could play classical music, which was unusual for saxophone players at the time, as well as jazz, Brazilian, and Latin music—it was incredibly versatile. However, the music itself always interested me more than the actual instrument. After playing the piano, I liked that the flute was mobile, so it stuck.

The instrument's versatility became particularly important as I developed my career. When I first moved to New York, I was doing a lot of classical gigs to make money, playing with great string players from Juilliard at private functions and weddings. We played chamber music, particularly Bach, where the counterpoint meant I was one line among many. There would be all these independent lines going on, and especially with Bach, you might play for five minutes feeling disconnected from the others, then suddenly cadence together before diverging again. I found that fascinating.

This experience significantly influenced how I approached jazz composition later on. In typical jazz formats of the time, the flute was often relegated to playing the melody while the rhythm section had all the interaction. I wanted to be more involved in the musical conversation, sometimes a middle voice rather than always the lead. This desire eventually led to my exploration of different ensemble formats and compositional approaches that would allow the flute to take on more varied roles.

Lawrence: So it wasn't that classic situation of a kid wanting to be in the school band, where they put the instruments out, and some kids gravitate toward the cello, and you find the one calling you?

Jamie: (laughter) I wish I could say it was even that purposeful! But sometimes, the most arbitrary choices lead us down the most interesting paths. The important thing was that I discovered all these possibilities, and they kept me engaged once I started playing. The instrument became a means of exploring different musical traditions and expressing ideas rather than an end in itself.

From Chaos Through Reflection

Lawrence: You've worked with ensembles of varying sizes, and it’s interesting to see something like Septet+ with this longevity. What keeps you drawn back to that format, and how stable has the lineup been?

Jamie: The Septet emerged during my master's studies in 1999. Before that, I had been working with quartet and quintet formats—my previous recordings featured Dave Douglas and Kenny Werner. My composition teacher suggested I create something bigger for my recital, which led to the septet’s creation.

Instead of the typical jazz horn section, I chose instrumentation that would give the flute more presence: alto saxophone/bass clarinet, trumpet, and French horn. This combination gave the flute more weight while offering a broader palette of colors. Through this ensemble, I found my voice as a composer.

While I love the textural possibilities of big band writing, I've always been selfish about my compositions—I want to play in them. Since I had never played in big bands, I focused on the septet format, where I could participate fully while still exploring complex arrangements.

The personnel has evolved but with remarkable stability. For the first decade, when I focused on classical influences, the lineup remained mostly consistent. Interestingly, many musicians weren't well-known when they joined but became increasingly prominent over time. This consistency was valuable because I could write specifically for their strengths, and they were fearless in approaching challenging material.

I often wrote things because I wanted to learn how to play them. In those days, you wouldn't find odd meters in the real book, so if you wanted to explore those elements, you had to write them yourself. The musicians might give me a skeptical look at first, but they would always rise to the challenge and bring more to the music than I could have imagined.

A significant shift occurred after my tours in South Asia. As I became more interested in incorporating those influences, it coincided with some personnel changes. George Colligan had moved to pursue teaching, Ralph Alessi was increasingly in demand, and I had begun collaborating with Amir El Saffar. I added Brad Shepik to the guitar to reference the string instruments common in South Asian music. This incarnation lasted nearly another decade before evolving into the current lineup, which now includes vocalists and additional percussion.

Lawrence: I wanted to ask about the stylistic choice of opening and closing the record with two instrumentals despite this being a record where you're introducing vocals and lyrics. What are you saying there?

Jamie: The opening piece, "In the Light of Day," was written earlier as part of my Shiva Suite for Nepal. I wrote that suite as a tribute after the earthquake, having just returned from my fourth visit there. It captures the intensity and chaos of life in places like Kathmandu—the cacophony of traffic, the lack of traffic signals, millions of motorcycles and vintage cars, no sidewalks, and a complete disregard for one-way street signs. There's a similar intensity in India, where the concept of personal space doesn't exist in the same way.

This piece took on new meaning in the context of COVID-19 and how it suddenly halted everything. It represents the manic pace of pre-pandemic life when everyone was focused on themselves and became increasingly aggressive and individualistic. Then, like a plague, COVID-19 stopped us in our tracks, forcing some to contemplate while others remained unchanged.

The album then moves through the various poems, each reflecting different aspects of our collective experience during this time. As we approach the end, pieces like "Dreams" offer more hope. The final instrumental, "In the Day of Light," takes elements from the opening piece but transforms them. I wanted each line to sometimes separate and harmonize, symbolizing how we can coexist while maintaining our individuality. The structure creates a journey from chaos through reflection to a resolution, suggesting the possibility of harmony without uniformity.

Visit Jamie Baum at jamiebaum.com and follow her on Facebook and YouTube. Purchase the Jamie Baum Septet+'s What Times Are These from Bandcamp or Qobuz and listen on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments