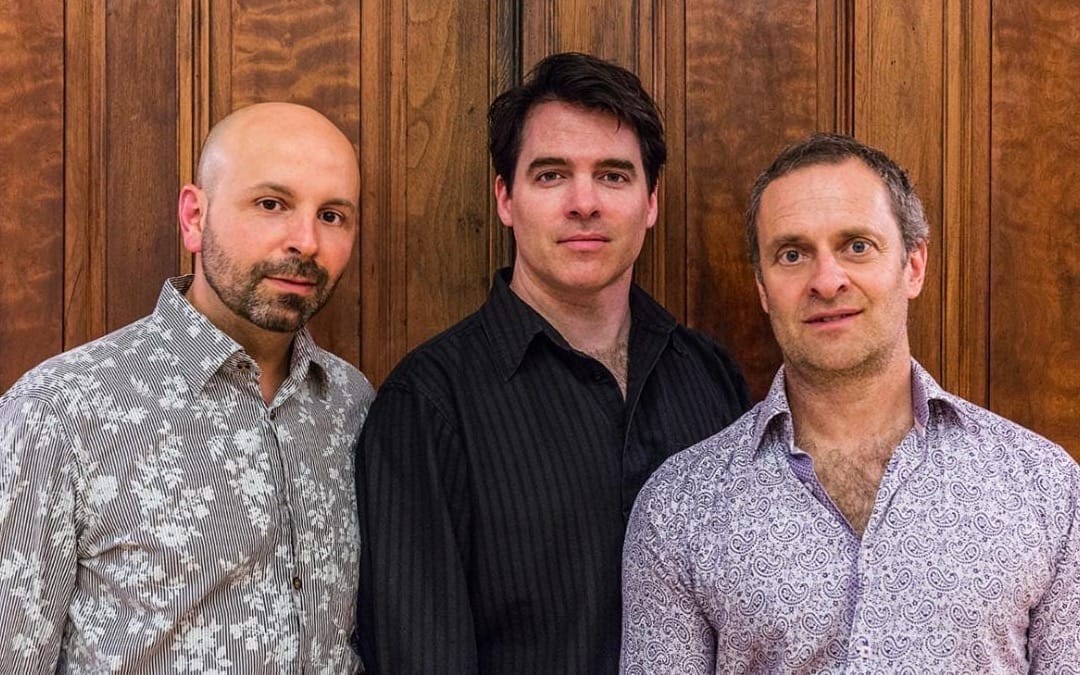

The members of WORKS—Michel Gentile, Daniel Kelly, and Rob Garcia—speak like old friends, finishing each other's thoughts as they discuss their music. The trio's combination of flute, piano, and drums emerged from Brooklyn's experimental jazz scene in 2007. While they've presented over 250 concerts through their nonprofit Connection Works and shared stages with everyone from Joe Lovano to the Mivos String Quartet, they waited eleven years to record their second album.

That album, Scouring for the Elements, reflects the musical trust developed across those years. Each musician brings original compositions to the project, while the album closes with four group improvisations that highlight their collective musical instincts.

Lawrence Peryer: I'm curious about what this configuration does for you as musicians. There's so much space, freedom, and harmonic room. What keeps you coming back to this lineup?

Michel Gentile: I've always liked playing in a trio setting because it feels like a trio can move in any direction or all directions at once. Everybody in the group is aware of those directions. Sometimes, we don't know where things will land with the three of us, and we just go for it.

In a trio, you can decide to make a left turn or a 360, and other people are highly aware of that. However, you can also choose to keep going in a straight line; somehow, that interaction becomes interesting. I always feel that a trio is a nice balance where you can be aware of what everybody else is playing, but you have room to make your own statement, and the meeting point of all those things becomes more interesting.

Lawrence: Daniel, how do you view your role?

Daniel Kelly: Because there's no bass player, there are a lot of directions we can go, and it frees me up considerably, giving me the flexibility that Michel was talking about. I can change the timbre when the moment calls for it.

As a pianist, it's challenging, too, because I want to create an interesting approach. I don't want just to play the bass with my left hand. I want to create something unique.

Lawrence: Rob, how is it different to play with a pianist as the bass player than with an actual bass player?

Rob Garcia: Sometimes Daniel plays a bass line with his left hand, and sometimes he's not. When he's not, there are many more possibilities of grooves, textures, or different ways to go. Not having a bass player allows the group to not fall into typical rhythmic trends that a jazz group may fall into, like just swinging for the solos.

Daniel has amazing ideas, and we play off each other. Sometimes, we just want to get into a groove, and we both feel it and then just go with it. The possibilities seem greater, or at least different, than if we had a bass player.

And then, of course, there's something about just the three of us as musicians because it's not like it would feel like this with any piano player. Daniel's a special cat.

Michel: I don't think we consider it as "How would Daniel fit the bass role?" We're thinking these three musicians with these three instruments are making the music that's available to us. It's unique because you won't find this kind of instrumentation. But I don't think we're trying to fit in or fill out any part of it that would be in a different context.

Lawrence: Could you talk about the luxury and longevity of your collaboration? What does it do for you in understanding how somebody will perform the composition or compose with these players in mind?

Rob: This group came together through the nonprofit Connection Works. I started thinking about starting a nonprofit in 2006 and thought of who would be great to have involved in this new organization. I asked Michel and Daniel, and they said yes.

We had played together before that in a group of mine called Sanga. I've known Michel since the nineties, and we've also done different things together before that. So, we came together to put on concerts and then said, "Well, let's just play as a trio."

That's how the trio started, and it inspired us to write music, particularly for this trio, with the specific people in mind and, of course, the instrumentation. But then we've expanded the trio many times, like adding special guests, expanding it to a quintet, expanding to a whole chamber orchestra, and adding a string quartet. We created these projects to write music for the trio with an expanded octet, and we've done many different configurations.

Lawrence: That's a fascinating part of your story—the amount of work you've created compared to the recorded output. What's going on there? Do you primarily view yourselves as a live ensemble?

Daniel: We've put out so much creativity, creating the concerts and music. Thankfully, for all those concerts through Connection Works, we're able to pay everyone well to be part of that, which is something very important for us to do. But in terms of going to the studio, I think it has to do with the economic realities—getting the studio, all the costs of mixing and mastering, all on top of our busy lives. We are all playing in many groups all the time, not just Connection Works and all the concerts we talked about. But this album is long overdue.

Michel: Something that happens also when you're a nonprofit like Connection Works is that you spend a lot of time writing grants to make the concert series work and to fund the special projects. It seems like every year, we write grants to fund recordings. Then you wait to see what happens with that. If it doesn't come through, we consider doing it ourselves. But there's another grant coming up, so you try that one.

Time slips away, and you realize we do this ourselves, or it won't happen. If we can get a grant somewhere, that's great, but if not, this music needs to be released. For this album, it felt like this music couldn't just sit there any longer.

Lawrence: Michel, could you talk about the role of your collaborations over the years? Do they contribute to the longevity?

Michel: They definitely enrich the culture of this trio. All those projects are important. If we're playing with Sheila Jordan, and the following time, we play with the Daedalus String Quartet, and the time after that, we're playing with Joe Lovano and Judi Silvano—all those things are very different. Still, the three of us are responding to the occasion.

We respond to each other but also make sure that our responses are appropriate for what's happening. This helps us grow in many different directions, so when we return to this trio setting, all of that has nestled inside us in different ways. Then, we all communicated all of that to each other. We all have that experience. The three of us experienced going through all these different things.

That's beautiful, and in terms of maintaining longevity, yes, it probably keeps us excited, interested, and motivated to keep working on stuff. However, I think this trio would exist regardless of whether we had worked with other people. But it does definitely influence how we play together.

Lawrence: Rob, you mentioned the genesis of all this through Connection Works. What gap in the scene, community, or educational landscape could Connection Works fill?

Rob: I was at a place where I wanted to create something bigger than just having a band, something that also served the community I was part of and served this tradition of music, this lineage known as jazz. I read a book by Marty Khan called Straight Ahead about the jazz business. There are many music business books, but at least at that time, that was the only one about jazz in particular, and in the book, he advocates very much for nonprofits.

Nonprofits exist in many other fields of art, including classical music, to support the arts. Every symphony orchestra and chamber orchestra is a nonprofit organization, as are visual art fields and theaters. The community needed more venues, more opportunities for musicians to perform, and more opportunities to get the music out there.

Over the past twenty or thirty years, probably even fifty years, there has been less and less support for creative music. While there is always a lot of creative music going on, the support for it and the money that can fund it seem to be less and less, and there are more and more musicians.

Lawrence: What goes into a professional creative life now? How do you keep it going?

Daniel: I have a lot of projects of my own that I tour around the country, and they have different connections outside of music. One project I did for over a decade was titled Portraits in Rhythm. I was commissioned by different performing arts centers to interview people, talk to them about their lives and stories, and write music about them. I incorporated the recorded interviews into the performance so that when people came to the performance, they and their friends, families, and neighbors would hear their stories and then hear this music that would uplift them.

I'm a creative musician with a jazz background, but the style of music varies greatly, whether it's in Memphis or whether it's in farmland upstate. I also have a project called Blind Visionaries, where I work with photos from different visually impaired and blind photographers who create stunning photography. I have this project called Shakespeare and Jazz, where I've written music to Shakespeare's words.

I found that a lot of the music connects to other interests outside of music. That combination has allowed me to find audiences and performances around the country that would be more challenging than if I were just presenting straight-up music.

Lawrence: The new record also stands out because you include notes about each song and composition. What's the hope in sharing that context?

Michel: I think it's just as simple as an honest, open sharing of what the song is about, what the genesis of the song was, or what we find exciting about it when we're performing live. Take my pieces—"Scouring for the Elements" was a piece I wrote for the performance we did with the sculptures of Jimmy Greenfield. I wanted to capture the spirit of that specific sculpture, which is three men made out of earth. They're leaning forward, nude, and they're clearly searching for something. That inspired me to write this piece of music, which happens to be a sort of canon with three voices. There's a searching—I was trying to convey that kind of searching.

Daniel: I love the visual and the emotional element of your song "Scouring for the Elements." But I also love that it's a canon, and there's a really interesting musical idea that you're exploring. It's fascinating how these notes are going by, but they're going by with different time groups of conceptions of time. I'm playing them slower than you're playing this group of notes and this melody you've arranged. But it's the same note group, going through faster. Then, Rob weaves those together in a different way.

That is a special way that we play together as a trio a lot of times, especially with Michel's songs. He'll say we're playing as three equal voices. And when we solo, we're doing that as well; we're playing musical phrases, but no one's taking the lead.

Michel: The rigor that Daniel speaks of is in service to the music, so I never want the form, the structure, or the technique to overpower the musicality. So, anytime I need to cheat, I cheat. But that piece, in particular, is indeed a true canon. It's an unconventional canon because the lines happen at different speeds, but it's still a canon.

Lawrence: How do you think about the improvised pieces on the record?

Daniel: Improvisation is life. I think compositionally when I improvise, but you're doing it in the moment and open to whatever ideas come. When you play one note, you play the following note, and then we're off. You can't stop and deliberate, and there's something that's freeing about that—just being in the moment and not having any ability to go back and revise. And if you're playing in the group context, it just makes it even more fun because Rob and Michel will play something to counteract that, and all of a sudden, we're working on something together.

When I'm at home improvising, this is where all the seeds of my pieces come from. I think there's a certain state of mind you can relax into when you improvise. You can get into a flow state, and when you're doing it in front of an audience, you're creating conditions to force a flow state to happen.

Michel: As Eric Dolphy once said, when you're improvising, it's gone into the air after it's over—you can never capture it again. It's gone. And that's okay, and something else will happen. But even though we're all improvising musicians playing in the culture of jazz, even when playing through set forms, where it goes will always be a surprise.

When I started improvising with people, I would want to coerce them into a direction and say, "Oh, you know, here's where we're going to go with this." But you don't have to do that when you trust people like we trust each other. As Rob said, I love playing these guys' compositions, and I feel the same way about any kind of improvising that they do—anything they bring to the table, I'm going to be excited to respond to, and I'm going to trust them entirely.

Rob: When it's fun, it's really fun. It's just the language we develop as drummers in particular styles of music, and then we figure things out on our own and develop our language. But I think it's the same for any instrument—when it's cooking and you're in the zone, there's nothing like it.

A big word for me is trust—trusting the people I'm with and trusting myself to know what to do. So I don't need to micromanage myself about what I'm going to play, and it's always better that way where I can just be in the moment. I'm listening, and it's just coming out of me. And then I'm just listening to the whole group, or I am the whole group. I'm playing all the parts. When that happens, it's like I'm exercising a muscle of getting into that space, into that flow zone. It's just way more enjoyable and meaningful.

Daniel: Talking about this makes me excited. I want to play music with these guys right now! After we finish, I'll probably go to the piano and improvise. Your life is an improvisation. You're figuring out as you go. You can have plans of what's going to happen, but there are unexpected things that come forward. You change your mind as you learn and you grow. And so yeah, like we said, improvisation is life, and to do it with these dear friends is a real gift.

Purchase the WORKS album Scouring for the Elements on Bandcamp or Qobuz and listen to it on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments